America is nearing the 250th anniversary of its revolutionary birth, the Declaration of Independence. July 4, 2026, will mark a milestone – and a time for reflection.

Yet as fascination with America’s founding endures, controversy colors how the revolution is taught across the United States. From contested efforts by The New York Times “1619 Project” to put slavery at the center of America’s story, to attempts to limit teaching about race and racism, partisanship surrounds the teaching of American history. Anniversaries can inspire public passion, but they can also open old wounds.

As an American historian and a naturalized citizen of the United States, I regard the American Revolution with both personal and professional interest. The fact that I grew up in the United Kingdom amuses my students to no end whenever we discuss the Revolutionary War. Sometimes, in my British-accented English, I remind them I did not personally grow up with King George. Teaching history is encouraging students to think critically about the past without dictating what emotions they should feel – patriotic or otherwise.

Sadly, in the U.S., the sort of objective historical knowledge once taken for granted now appears to be waning. According to the National Assessment of Educational Progress, just 13% of eighth graders in 2023 ranked “proficient” in American history. A 2010 survey found that 26% of adults could not identify from whom America declared its independence, with China, Mexico and France among the responses.

America divorcing France would have been news to Gilbert du Motier, better known as the Marquis de Lafayette. His commitment to the new country not only helped secure its independence, but it also helped solidify American identity decades later.

Key alliance

A privileged aristocrat who served in both the American and French revolutions, Lafayette went to war at age 19. Commissioning and equipping his own expedition across the Atlantic in 1777, he fought in many battles against the British, including decisive action at Yorktown. Earning George Washington’s confidence, Lafayette attained the rank of major general in the Continental Army.

Lafayette’s enrollment in the U.S. military predated the 1778 alliance between his home country and the United States. Eventually, France’s alliance turned the tide against Great Britain on land and at sea. By the war’s end, the French had supplied some 12,000 soldiers, 22,000 sailors and dozens of warships to the American cause, plus huge financial resources. When Lafayette volunteered, however, he was one of just a few foreign volunteers – and the most acclaimed.

“Nowadays,” as historian Sarah Vowell conceded, Americans think of Lafayette as “a place, not a person.” But an abundance of cities, counties and thoroughfares named after the revolutionary hero attest to his former celebrity. During World War I, U.S. troops sailed to France under the slogan “Lafayette here we come,” promising to repay America’s debt of gratitude to France.

A growing country

Older Americans may recall the U.S. bicentennial of 1976, marked with much pageantry and even a state visit by Queen Elizabeth II. America’s semicentennial, however – the 50th anniversary of independence – played a far greater role shaping the idea of America in the minds of its citizens.

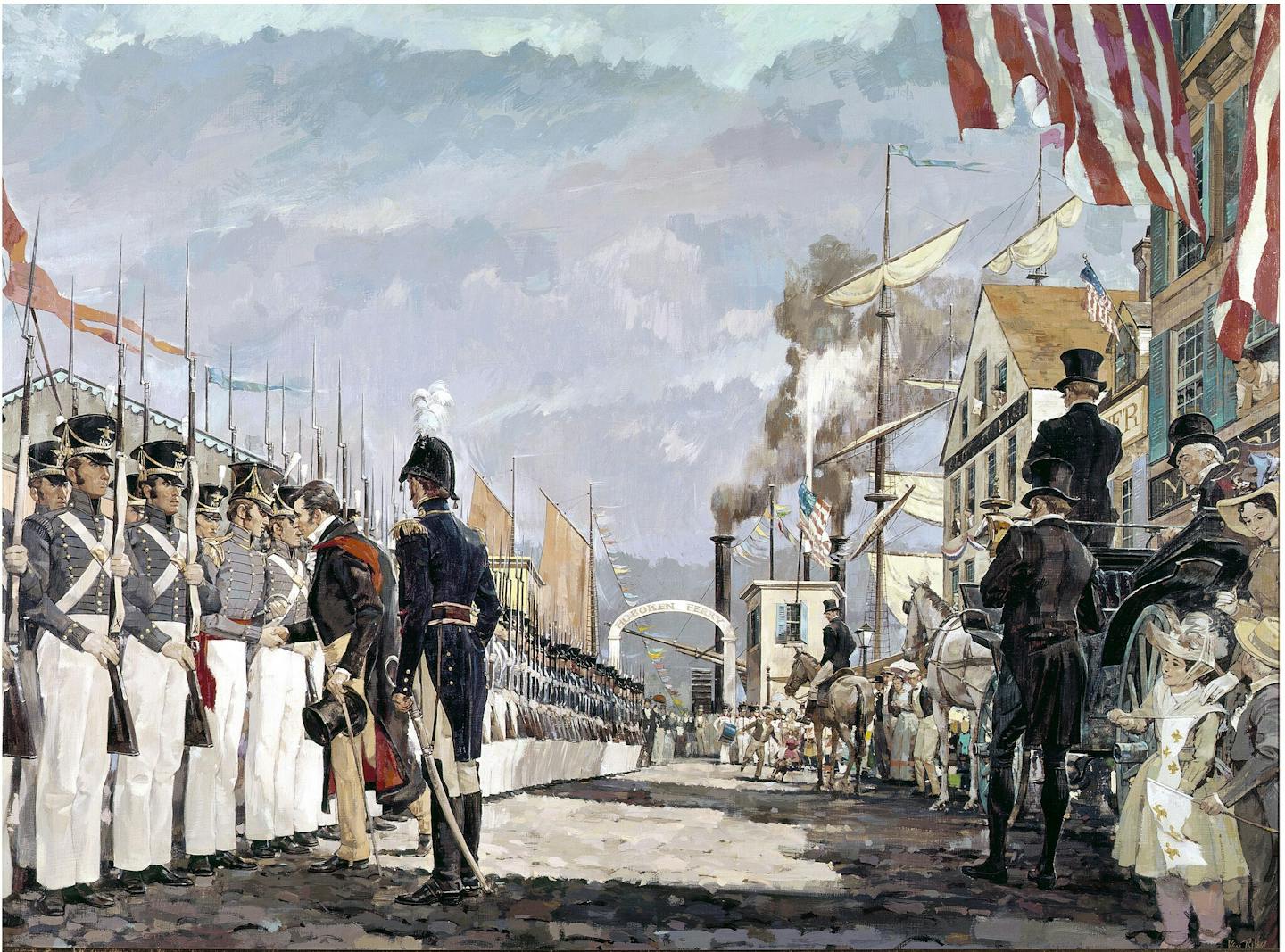

Lafayette starred in the buildup to this 1826 commemoration, the first of its kind at the national level. President James Monroe, a fellow veteran of the War of Independence, invited Lafayette to be “the guest of America,” honored as the last living major general of the Continental Army. Beginning in July 1824, at the age of 66, Lafayette embarked on a triumphal tour of all 24 states then comprising the union – nearly double the original 13.

As Lafayette headed west, borne by horse-drawn carriage, steamboat and canal barge, he journeyed across a changing America. Nowhere was America’s economic and demographic growth more evident than Cincinnati, where a crowd of 50,000 welcomed Lafayette in May 1825. Once a small frontier town, Cincinnati was growing faster than any comparably sized city in the nation: Its population increased from around 15,000 to roughly 115,000 in the quarter century following Lafayette’s visit.

He addressed his audience with emotion: “The highest reward that can be bestowed on a revolutionary veteran is to welcome him with a sight of the blessings which have issued from our struggle for independence, freedom and equal rights.”

Lafayette gave human face to America’s national commemoration. He granted citizens of frontier states like Ohio – hitherto excluded from the revolutionary narrative – license to celebrate themselves. High turnouts in western stops such as Cincinnati reflected enthusiasm for grand spectacles. They also reflected the growth of America’s print media, which had advertised his visit, and improved transportation in formerly remote regions of the country.

Lafayette’s tour culminated with a September 1825 state banquet in Washington, D.C., hosted by the new president, John Quincy Adams. Adams – the son of America’s second president, John Adams – praised “that tie of love, stronger than death,” connecting Lafayette “for the endless ages of time, with the name of Washington.”

Rose-colored glasses

The enthusiasm that welcomed Lafayette 200 years ago was authentic. But like all good history lessons, Lafayette’s legacy is open to interpretation.

His grand tour cemented the myth of “the Era of Good Feelings”: a golden age of American political harmony. In reality, the seeds of America’s civil war were already evident. Missouri’s 1820 admission to the union threatened the country’s precarious balance between states that opposed slavery and states that allowed it – a crisis Thomas Jefferson warned was “a fire bell in the night.”

Likewise, Lafayette’s lionization in the western United States coincided with the ongoing forced removal of Indigenous people. Ohio, for example, forcibly removed its last Native American tribe in 1843.

Despite the uses and abuses of historical memory and the aversion of modern historians toward hero-worship, Lafayette remains a charismatic figure – a “citizen of two worlds” who championed both abolitionism and women’s rights. I believe his fading public memory indicates a troubling amnesia. America’s anniversary offers the opportunity to reconsider his legacy, alongside revolutionary stories of Americans from all walks of life.

As Lafayette wrote home following the British army’s surrender in 1781: “Humanity has won its battle. Liberty now has a country.”

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Matthew Smith, Miami University

Read more:

- During the American Revolution, Brits weren’t just facing off against white Protestant Christians − US patriots are diverse and have been since Day 1

- How Jefferson and Madison’s partnership – a friendship told in letters – shaped America’s separation of church and state

- Revisiting Middletown, Ohio – the Midwestern town at the heart of JD Vance’s ‘Hillbilly Elegy’

Matthew Smith does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The Conversation

The Conversation

LiveNOW from FOX Politics

LiveNOW from FOX Politics Press of Alantic City Business

Press of Alantic City Business PennLive Pa. Politics

PennLive Pa. Politics