In our guide to the classics series, experts explain key works of literature

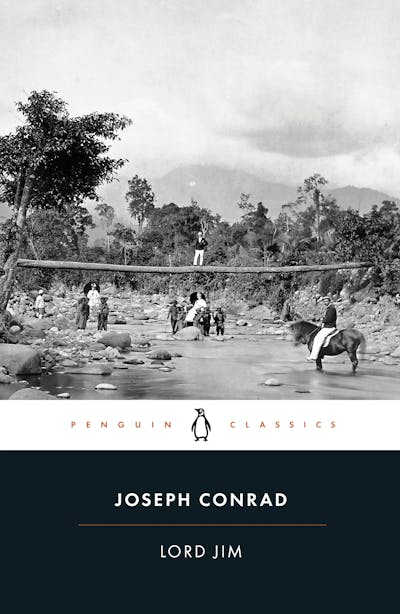

For me, no novel provides a better account of what we humans are up against in our pursuit of the true and the good than Joseph Conrad’s Lord Jim (1900). It does this alongside Conrad’s other great works, Heart of Darkness (1899) and Nostromo (1904).

Lord Jim reveals that, even in our secular age, we remain creatures of ineluctable faith. Our sense of being good derives from this faith. But the kicker is that, perhaps inevitably, it is a bad faith, because what we do for it – how we reaffirm our faith – is all too often not good.

Conrad scholar Royal Roussel provides the best articulation of this when he says that Conrad’s novels are concerned with “the self’s alienation from the source of its own existence”.

Once we grasp the form of this alienation, we have a key for understanding much that is dark within humanity, from the atrocities of colonisation that Conrad writes about, to the dubious nationalisms and identity politics of our own time. It provides insight into the inability many of us have to scrutinise our own devotions and failings.

Biography and legacy

Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski was born in 1857 in Berdychiv, which is now in Ukraine. At the time, Berdychiv was part of the Russian empire.

Conrad’s parents were intellectuals of noble heritage. They were involved in the Polish nationalist movement, which aimed to preserve Polish heritage in the face of Russification. They were exiled to Russia and died there as a result of the harsh conditions, leaving 11 year old Józef an orphan.

When he was 16, Conrad moved to France and became a sailor. Several years later, he joined the British Merchant Navy, where he rose to the rank of captain. The sea often features in Conrad’s novels, where its vastness stands for many things, including human insignificance, limitless adventure and globalisation.

Conrad, who is one of the very best English prose stylists, only began to seriously study English, his third language, in his 20s. He started writing in his 30s and, in 1894, he gave up sailing and settled in England.

The legacy of Conrad’s writing is immense. As literary critic John Marx puts it, Conrad’s work “announces that the modernist break has occurred”. In his writing, we see the shift to complex narrative structures, unreliable narrators – narrators who are themselves, like Marlow in Lord Jim, characters in the story – and a focus on the psychological and the existential.

Heart of Darkness regularly appears in top-novel lists (it is number 31 in this one); its critique of European colonialism has become foundational to how we view the colonial enterprise. The novel was remade as the film Apocalypse Now, which presents the Vietnam War in the same dark light. My favourite homage to Conrad is that the ship names in the Alien franchise – the Nostromo, the Sulaco and the Patna – are drawn from Conrad’s novels.

An overview

The title of Lord Jim is ironic, even mocking to a degree. Tragically so.

Jim – that’s all we know of his name – is a competent young sailor from solid English stock. His father is a parson: a dispenser of “easy morality”, as Marlow tellingly observes.

Jim’s great test comes when he is first mate – second in command – on the steam ship Patna. The dilapidated Patna, which is carrying 800 Muslim pilgrims to a Red Sea port, strikes something and the front section fills with water. A rusty bulkhead, which seems like it will give way at any moment, is all that stops the ship from sinking.

Certain the ship will go down and knowing that there are not enough lifeboats for the passengers, the crew, other than Jim, abandons ship. At the last minute, Jim, in a moment of cowardice, leaps from the Patna to join the crew.

Miraculously, the Patna doesn’t sink, and Jim and the crew must face the Marine Court of Inquiry. All but Jim abscond – they are lesser men. Jim loses his Certificate of Competency and cannot continue as a sailor.

Marlow helps Jim find employment elsewhere. But the notorious story of the Patna, which has become known around the maritime world, follows him wherever he goes.

He eventually seeks refuge in a remote village in the Malay archipelago, where he gains redemption by becoming a leader. Yet the Patna episode continues to govern his destiny.

The knitting machine and moral solitude

Conrad lays out his philosophy in his many letters. A key letter was written to Scottish radical R.B. Cunninghame Graham on December 20, 1897, not long before Conrad produced his most important works.

In the letter, Conrad bleakly imagines society as a metaphorical “knitting machine” that knits “time, space, pain, death, corruption, despair and all the illusions”, such that “nothing matters”. The machine is remorseless, incapable of being influenced – “you can’t even smash it”.

Conrad’s inhuman knitting machine, which “knits us in and knits us out”, is very different from the cheery, liberal social contract, in which society is constituted by rational individuals giving up some freedoms, such as the freedom to kill or rob, in return for other freedoms, such as the freedom from being killed or robbed.

In Lord Jim, the knitting machine appears as the “sovereign power” and “the spirit of the land” – Marlow speaks about both. These concepts have nationalist overtones, and this is understandable, seeing as the nation is something to which people belong. But ultimately, for Conrad, the knitting machine is less tangible than the nation. It is the seemingly upright world of industry and work and public life to which Marlow and Jim himself belong.

The crux of Conrad’s philosophy is that our relationship with this knitting machine is existential. The best account of this appears in Under Western Eyes (1911), where we read:

Who knows what true loneliness is – not the conventional word, but the naked terror? To the lonely themselves it wears a mask. The most miserable outcast hugs some memory or some illusion. Now and then a fatal conjunction of events may lift the veil for an instant. For an instant only. No human being could bear a steady view of moral solitude without going mad.

In my arrogant opinion, no concept is more important than moral solitude. The short of it is that if we are removed from our world – from the knitting machine or the sovereign power or the spirit of the land (or whatever we want to call it) – we psychologically disintegrate.

But why does all this matter? It matters, once again, because our sense of being good derives from our belonging, yet that to which we belong is not necessarily good when measured from the perspective of reason – or even, dare I say, conscience.

Marlow, who is a man of reason and conscience, speaks of “the doubt of the sovereign power enthroned in a fixed standard of conduct”. About this doubt he says:

It is the hardest thing to stumble against; it is the thing that breeds yelling panics and good little quiet villanies; it’s the true shadow of calamity.

Jim never doubts the knitting machine. As Marlow says, Jim is “a straggler yearning inconsolably for his humble place in the ranks”. It is those who observe Jim who doubt. And Marlow’s doubt is central; it roils on for hundreds of pages. He sees the truth, which includes the corruption that can come with pursuing truth:

And yet is not mankind itself, pushing on its blind way, driven by a dream of its greatness and its power upon the dark paths of excessive cruelty and of excessive devotion? And what is the pursuit of truth, after all?

However, he cannot leave the ranks:

For a moment I had a view of a world that seemed to wear a vast and dismal aspect of disorder, while, in truth, thanks to our unwearied efforts, it is as sunny an arrangement of small conveniences as the mind of man can conceive. But still it was only a moment: I went back into my shell directly. One must – don’t you know? – though I seemed to have lost all my words in the chaos of dark thoughts I had contemplated for a second or two beyond the pale. These came back, too, very soon, for words also belong to the sheltering conception of light and order which is our refuge.

The failure of human connection

Lord Jim, like quite a few major works of literature and film, explores what occurs when a masculine public realm, characterised by work, status and brutality, intersects with the feminine. Hamlet, Catch-22, and The Godfather all come to mind.

The first two thirds of Lord Jim are almost entirely about this male world. The last third is dominated – conceptually at least – by Jim’s relationship with Jewel, the daughter of a Dutch trader and a Malay woman, who lives in the remote village of Patusan.

Jewel is entirely devoted to Jim and Jim is entirely devoted to Jewel – almost. She is unworldly, but she nonetheless grasps the truth of men and women (which in our contemporary world, reconfigured by postmodern relativism, is unspeakable). She senses that Jim serves some power that exceeds their relationship. She asks Marlow:

What is this thing? Is it alive? – is it dead? I hate it. It is cruel. Has it got a face and a voice – this calamity?

And she believes that Jim’s devotion to this power will separate them: “They [men] always leave us [women].”

In response Marlow lies – as he does to Kurtz’s betrothed at the end of Heart of Darkness – saying that nothing could separate Jim from her.

Jim does leave Jewel. He allows himself to be killed – sacrificed – to retain his honour. It is ridiculous. In the novel’s penultimate paragraph, Marlow reflects:

He goes away from a living woman to celebrate his pitiless wedding with a shadowy ideal of conduct. Is he satisfied – quite, now, I wonder? We ought to know. He is one of us – and have I not stood up once, like an evoked ghost, to answer for his eternal constancy? Was I so very wrong after all?

Marlow’s refrain throughout Lord Jim is that Jim is “one of us”. This elevates Jim’s story to the level of archetype. It impels us all to ask: what aspects of our humanity do we sacrifice to the implacable knitting machine?

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Jamie Q. Roberts, University of Sydney

Read more:

- Who was Jane Austen’s best heroine? These experts think they know

- In Jane Austen’s Persuasion, respite is a key ingredient for romance

- Animal Farm at 80: why the animals really matter in Orwell’s parable about communism

Jamie Q. Roberts does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The Conversation

The Conversation

The List

The List Raw Story

Raw Story New York Post

New York Post The Daily Beast

The Daily Beast