Some of the most enduring ancient myths in the Persian world were centred around gardens of almost unimaginable beauty and opulence.

The biblical Garden of Eden and the Epic of Gilgamesh’s Garden of the Gods are prominent examples. In these myths, paradise was an opulent garden of tranquillity and abundance.

But how did this concept of paradise originate? And what did these beautiful gardens look and feel like in antiquity?

Pairi-daēza is where we get the word ‘paradise’

The English word “paradise” derives from an old Persian word pairidaeza or pairi-daēza, which translates as “enclosed garden”.

The origins of paradise gardens lie in Mesopotamia and Persia (modern Iraq and Iran).

The Garden of the Gods from the Epic of Gilgamesh from about 2000 BCE is one of the earliest attested in literature.

Some argue it was also the inspiration for the legend of the Garden of Eden in the book of Genesis. In both of these stories, paradise gardens functioned as a type of utopia.

When the Achaemenid kings ruled ancient Persia (550–330 BCE), the development of royal paradise gardens grew significantly. The paradise garden of the Persian king, Cyrus the Great, who ruled around 550 BCE, is the earliest physical example yet discovered.

During his reign, Cyrus built a palace complex at Pasargadae in Persia. The entire complex was adorned with gardens which included canals, bridges, pathways and a large pool.

One of the gardens measured 150 metres by 120 metres (1.8 hectares). Archaeologists found evidence for the garden’s division into four parts, symbolising the four quarters of Cyrus’s vast empire.

Technological wonders

A feature of paradise gardens in Persia was their defiance of often harsh, dry landscapes.

This required ingenuity in supplying large volumes of water required for the gardens. Pasargadae was supplied by a sophisticated hydraulic system, which diverted water from the nearby Pulvar River.

The tradition continued throughout the Achaemenid period. Cyrus the Younger, probably a descendant of Cyrus the Great, had a palace at Sardis (in modern Turkey), which included a paradise garden.

According to the ancient Greek writer, Xenophon, the Spartan general Lysander visited Cyrus at the palace around 407 BCE.

When he walked in the garden, astounded by its intricate design and beauty, Lysander asked who planned it. Cyrus replied that he had designed the garden himself and planted its trees.

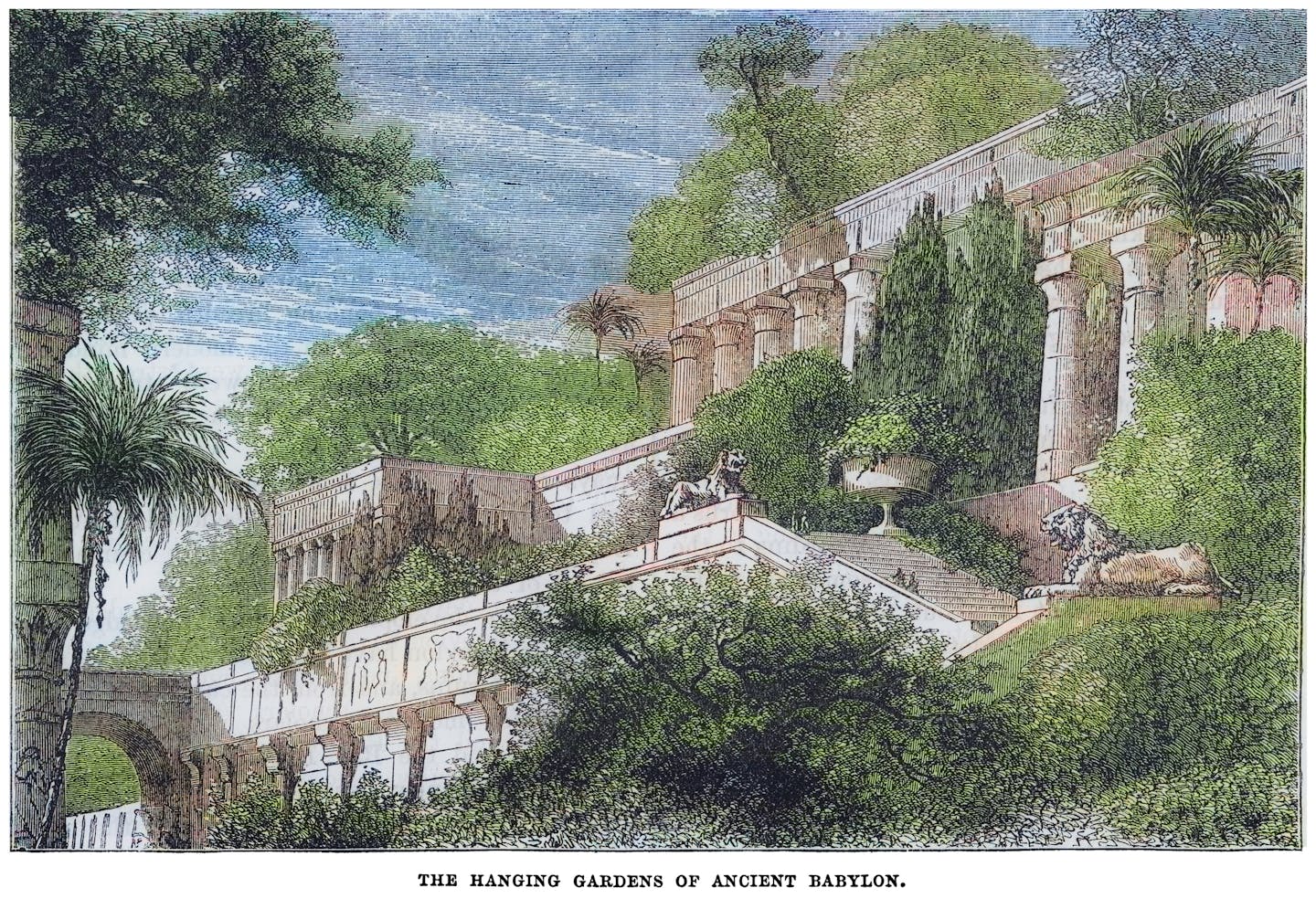

Perhaps the ultimate ancient paradise garden was the legendary Hanging Gardens of Babylon.

In one tradition, the gardens were built by the neo-Babylonian King, Nebuchadnezzar II (605–562 BCE).

The gardens were so magnificent and technologically advanced they were later counted among the Seven Wonders of the World.

In a later Roman account, the Hanging Gardens consisted of vaulted terraces resting on cube-shaped pillars.

Flowing water was a key feature, with elaborate machines raising water from the Euphrates river. Fully grown trees with vast root systems were supported by the terraces.

In another account, the Hanging Gardens were built by a Syrian king for his Persian wife to remind her of her homeland.

When the Sasanian dynasty (224–651 CE) came to power in Persia, its kings also built paradise gardens. The 147-hectare palace of Khosrow II (590–628 CE) at Qasr-e Shirin was almost entirely set in a paradise garden.

The paradise gardens were rich in symbolic significance. Their division into four parts symbolised imperial power, the cardinal directions and the four elements in Zoroastrian lore: air, earth, water and fire.

The gardens also played a religious role, offering a glimpse of what eternity might look like in the afterlife.

They were also a refuge in the midst of a harsh world and unforgiving environments. Gilgamesh sought solace and immortality in the Garden of the Gods following the death of his friend Enkidu.

According to the Bible, God himself walked in the Garden of Eden in the cool of the evening.

But in both cases, disappointment and distress followed.

Gilgamesh discovered the non-existence of immortality. God discovered the sin of Adam and Eve.

Paradise on Earth

The tradition of paradise gardens continued after the Islamic conquest of Persia in the 7th century CE.

The four-part gardens (known as chahar-bagh) of the Persian kingdoms were also a key feature of the Islamic period.

The Garden of Paradise described in the Quran comprised four gardens divided into two pairs. The four-part garden became symbolic of paradise on Earth.

The tradition of paradise gardens has continued in Iran to the present day.

Nine paradise gardens in Iran are collectively listed as a UNESCO World Heritage site. The Eram garden, built in about the 12th century CE, and the 19th-century Bagh-e Shahzadeh are among the most splendid.

Today, the word “paradise” evokes a broader range of images and experiences. It can foster many different images of idyllic physical and spiritual settings.

But the magnificent enclosed gardens of the ancient Persian world still inspire us to imagine what paradise on Earth might look and feel like.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Peter Edwell, Macquarie University

Read more:

- Chaos gardening – wild beauty, or just a mess? A sustainable landscape specialist explains the trend

- Cultivating for color: The hidden trade-offs between garden aesthetics and pollinator preferences

- Allotments are vanishing when the UK urgently needs more of them

Peter Edwell receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

The Conversation

The Conversation

CBS News

CBS News ABC News Video

ABC News Video TMZ

TMZ Bozeman Daily Chronicle Sports

Bozeman Daily Chronicle Sports