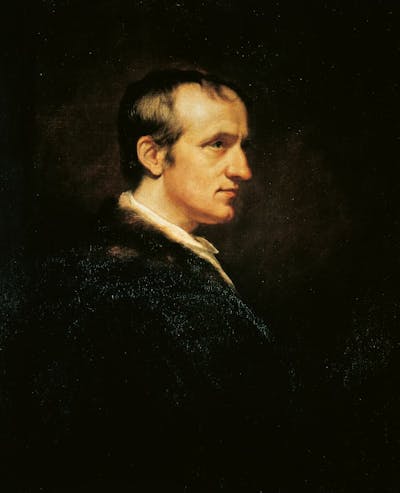

No one uses “Malthusian” as a compliment. Since 1798, when the economist and cleric Thomas Malthus first published “An Essay on the Principles of Population,” the “Malthusian” position – the idea that humans are subject to natural limits – has been vilified and scorned. Today, the term is lobbed at anyone who dares question the optimism of infinite progress.

Unfortunately, almost everything most people think they know about Malthus is wrong.

The story goes like this: Once upon a time, an English country parson came up with the idea that population increases at a “geometrical” rate, while food production increases at an “arithmetical” rate. That is, population doubles every 25 years, while crop yields increase much more slowly. Over time, such divergence must lead to catastrophe.

But Malthus identified two factors that reduced reproduction and held off disaster: moral codes, or what he called “preventative checks,” and “positive checks,” such as extreme poverty, pollution, war, disease and misogyny. In the all-too-common caricature, Malthus was a narrow-minded clergyman who was bad at math and thought the only solution to hunger was to keep poor people poor so they had fewer babies.

Understanding Malthus in a broader context reveals a very different character. As I discuss in my 2025 book “Impasse: Climate Change and the Limits of Progress,” Malthus was an innovative and insightful thinker. Not only was he one of the founding figures of environmental economics, but he also turned out to be a prophetic critic of the belief that history tends toward human improvement, which we call progress.

God and science

On the topic of progress, Malthus knew what he was talking about.

He was raised and educated by dissenters: progressivist English Protestants who advocated the separation of church and state. He was taught by the radical abolitionist Gilbert Wakefield, and his father was a friend and admirer of the Enlightenment philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, whose ideas helped inspire the French Revolution.

Despite struggling with a cleft palate, Malthus distinguished himself at Cambridge, where he studied applied math, history and geography. Going into the clergy was a common choice for educated young men of middling means, and Malthus was able to secure a parsonage in Wotton, Surrey. But that didn’t mean giving up his interest in social science.

“An Essay on the Principle of Population” was shaped by Malthus’ theological views, but it is also a deeply empirical work and became more so as he revised it in later editions. His argument about geometrical and arithmetical growth rates, for instance, was based on the rapid population growth witnessed in the American Colonies.

It was also based on what he saw happening around him in Britain. Over the final decades of the 18th century, Britain was wracked by repeated food shortages and riots. The population rose from 5.9 million to 8.7 million, an increase of almost 50%, while agricultural production lagged. In 1795, hungry Londoners mobbed King George III’s coach demanding bread.

Boundless optimism

But why was Malthus talking about population in the first place? As Malthus himself explains, his essay was inspired by an argument with a friend about the journalist and novelist William Godwin – best known today as the father of Mary Shelley, author of “Frankenstein.”

Malthus and Godwin had similar backgrounds. Both came from dissenting middle-class families, were educated in progressive schools and began their careers as ministers. But Godwin’s extreme radicalism put him at odds even with his fellow dissenters, and he soon left the pulpit to take up the pen.

The book that made Godwin’s name and provoked Malthus was “An Enquiry Concerning Political Justice,” published in 1793. Today, it is considered a founding text of philosophical anarchism. Originally, however, Godwin’s “Enquiry” was seen as a thunderous articulation of Enlightenment progressivism.

Godwin argued that all social problems could be eliminated by reason’s proper application. He advocated abolishing marriage, redistributing property and eliminating government. What’s more, he asserted that progress led inevitably to a utopian world, where humans will no longer have to reproduce because we’ll be immortal:

“There will be no war, no crimes, no administration of justice as it is called, and no government. … But beside this, there will be no disease, no anguish, no melancholy and no resentment. Every man will seek with ineffable ardour the good of all.”

Such things would come about in due time, Godwin assured his readers, solely through the spread of rational discussion.

From his poverty-stricken parsonage in Wotton, Malthus saw things differently. Historian Robert Mayhew describes Wotton at the time as an industrial wasteland afflicted by “agrarian poverty … high birth rates and short life spans.” Studying history led Malthus to conclude that societies moved not in an ever-ascending line of progress but in cycles of expansion and decline. Godwin’s utopian story didn’t seem to match the evidence.

Reform – within reason

Malthus aimed to puncture Godwin’s grandiloquent progressivism. But he wasn’t saying positive change was impossible, only that it was limited by the laws of nature.

“An Essay on the Principles of Population” was his attempt to ascertain where some of those limits might lie, so that policy could respond to social problems effectively, rather than exacerbating them by trying to achieve the impossible. As a writer and active member of the Whig Party, Malthus was a reformer who advocated free national education, the extension of suffrage, the abolition of slavery and free medical care for the poor, among other programs.

Since then, science and industry have made incredible advances, leading to changes Malthus would have scarcely found credible. When his essay was published, the global human population was around 800 million. Today it is over 8 billion, a tenfold increase in little more than two centuries.

Over that time, proponents of progress have scorned the idea that humans are subject to natural limits and denigrated anyone who questioned the fantasy of infinite growth as “Malthusian.” Yet Malthus remains important because his pessimistic account of society so clearly articulates an insight that refuses to be repressed: The laws of nature apply to human society.

Indeed, “the Great Acceleration” in human development and impact over the past 80 years may have pushed society to the breaking point. Scientists warn that we’ve exceeded six of the nine boundary conditions for sustainable human life on Earth and are close to exceeding a seventh.

One of those conditions is a stable climate. Global warming threatens to not only raise sea levels, increase wildfires and supercharge storms, but also amplify drought and disrupt global agriculture.

Malthus may not have foreseen the developments that fueled human growth over the past two centuries. But his fundamental insight into the limits of growth has only become more relevant. As we face accelerating global ecological crisis, it may be time to revisit the pessimistic idea that we live in a world with limits. Reconsidering what we mean by “Malthusian” might be a good place to start.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Roy Scranton, University of Notre Dame

Read more:

- Why is free time still so elusive?

- Fears that falling birth rates in US could lead to population collapse are based on faulty assumptions

- Does raising the minimum wage kill jobs? Economists have been trying to answer this question for a century – and finally starting to gather data

Roy Scranton received funding from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation.

The Conversation

The Conversation

TIME

TIME CBS News

CBS News NBC News

NBC News Reuters US Domestic

Reuters US Domestic Raw Story

Raw Story Washington Examiner

Washington Examiner  New York Post Video

New York Post Video Women's Wear Daily Lifestyle

Women's Wear Daily Lifestyle 5 On Your Side Sports

5 On Your Side Sports