This month, the Australian-made video game Silksong became one of the most played titles worldwide.

Created by Team Cherry, a three-person indie studio in Adelaide, the sequel to 2017’s Hollow Knight shows how small studios can capture global attention.

Its success matters not just for its artistry but because it demonstrates why video games are more than entertainment. They are central to how people play, connect and participate in culture.

A global moment for a small Australian studio

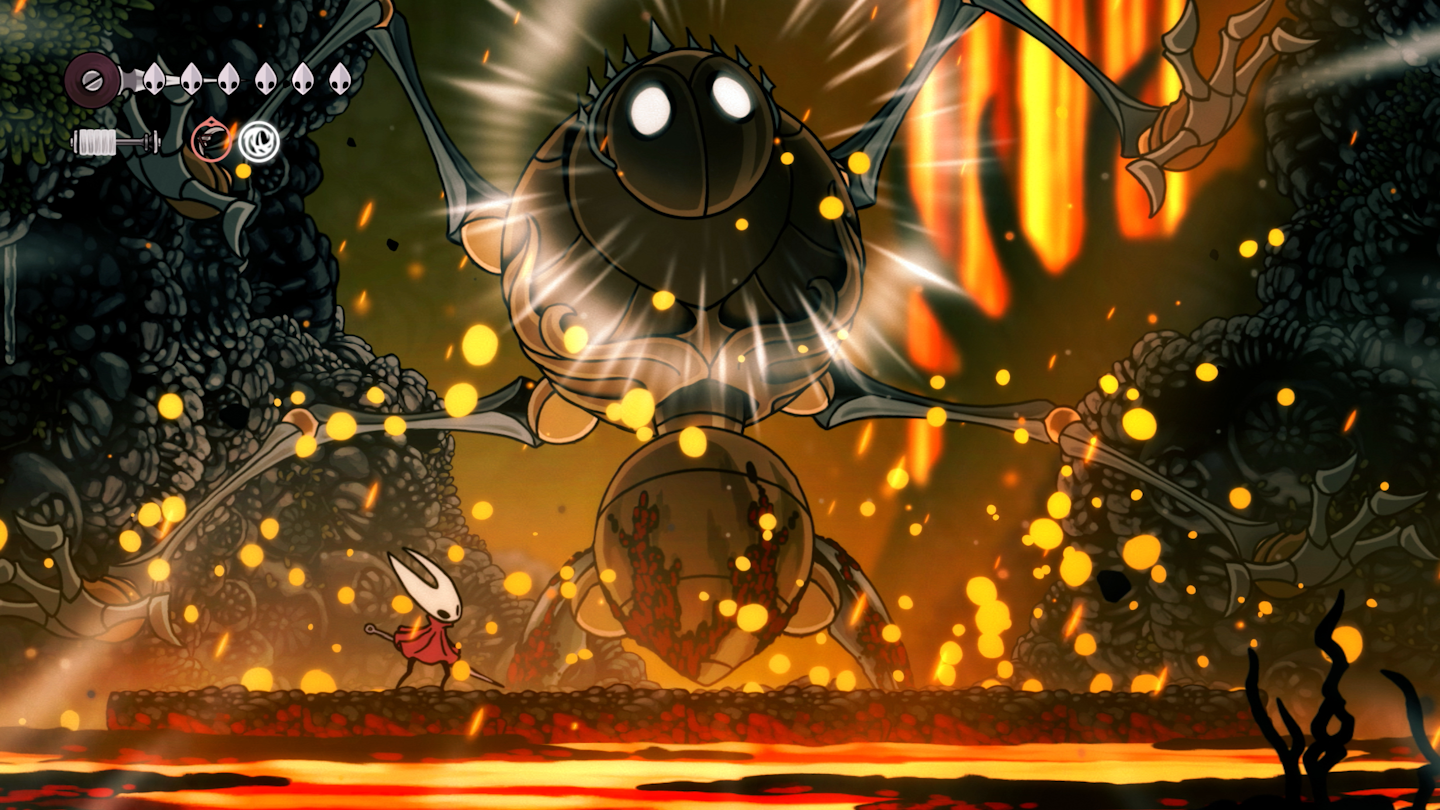

Hollow Knight and Silksong are atmospheric side-scrolling Metroidvania adventures set in hand-drawn underground kingdoms.

While attempting to uncover the mysteries of fallen realms and restore balance to their worlds, players encounter insect-like characters, uncover secrets and face formidable bosses.

The games are punishing, but each hard-won success makes the struggle worthwhile.

On launch day, Silksong rose to the top of Steam’s charts, with more than half a million people playing at once.

Critics praised it as one of the finest action video games of the decade. Others noted its steep difficulty, while Polygon published a dissenting review. Metacritic currently rates the game 92 out of 100, with a user review score of 9.1 out of 10.

The excitement of the new release had a ripple effect. Hollow Knight surged again, breaking records seven years after release.

For a small Adelaide studio to dominate global charts with two titles at once is extraordinary.

Why these games matter to players

As someone who has played games for over 40 years and now researches immersive media and game technology, I see more than just stylish combat and art. Hollow Knight and Silksong are built on the psychology of play. They punish mistakes but reward resilience.

Psychologists call this state flow – the same feeling as losing yourself in a book or a sport when challenge and skill are perfectly balanced. Every setback teaches, every retry builds mastery, every breakthrough delivers satisfaction.

Flow and immersion in games can build presence – the feeling of actually being inside the world rather than just observing it – and wellbeing. Scholars such as linguist James Paul Gee have long argued that video games can teach us how to learn, by placing players in problem-solving environments where they must experiment, fail, adapt and try again until they master a challenge.

Games aren’t just entertainment: they are complex systems that show how people acquire knowledge, test ideas and build skills through active engagement.

A 2025 report found 82% of Australians play video games. The average player is 35, and for the first time, women made up the majority of players. Families play to connect, adults to relax after work, and two-thirds of older Australians continue to play in retirement.

Nine in ten Australians also believe games help build confidence and resilience. Action-adventure is the most popular genre – exactly what Team Cherry has mastered.

A small but global industry

These cultural breakthroughs emerge from an industry smaller than many realise. The Australian Game Development Survey 2024 reported just 2,465 people employed nationwide in game development, generating A$339 million in annual revenue. A remarkable 93% of that comes from exports.

More than half of local studios are less than five years old, while a quarter have lasted more than a decade. Most focus on original ideas rather than contract work (projects made on behalf of another company, such as licensed games or porting existing titles).

While contract work can provide reliable income, it rarely allows studios to retain creative control. Developing original intellectual property showcases Australia’s creativity to the world – but it also exposes studios to greater financial risk if a game fails to find an audience.

Globally, gaming now generates more revenue than film and music combined. Yet in Australia, the sector still fights for recognition as a cultural industry equal to screen and television. Policies like the digital games tax offset have provided stability, but early-stage investment remains a hurdle.

The risks of global fame

Global attention also brings sudden risks. Within days of release, Silksong faced a flood of negative reviews on Steam from players in China upset with its translation. More than 14,000 one-star reviews pushed its score to “mixed”, despite strong critical acclaim.

It shows how player feedback can highlight legitimate concerns – in this case, the need for better localisation.

I have previously written about the benefits of online feedback and published articles on community feedback on game production. Team Cherry responded swiftly, promising to improve the translation.

Even the most successful indie studios must navigate the volatility of global audiences.

Why this matters

The story of Hollow Knight and Silksong is about more than two acclaimed video games. It shows how Australian indie studios can influence global play, and how success can be both celebrated and contested.

Games are now central to everyday life. They connect families, help manage stress, and build communities across borders. They are also one of Australia’s most dynamic cultural exports.

Hollow Knight and Silksong prove that a modest Adelaide studio can captivate millions. But without consistent investment, publishing opportunities and education pipelines, the next Team Cherry may never emerge.

If Australia wants to keep shaping how the world plays, video games must be recognised alongside film, TV and music as a cultural and economic force. Games are already bigger than both industries combined. They should no longer be treated as an afterthought.

When Australians play, the world takes notice.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: James Birt, Bond University

Read more:

- Lesbian Space Princess is a cheeky, intergalactic romp that turns the sci-fi genre on its head

- New horror film Went Up The Hill is a chilling exploration of trauma and memory

- Over-the-top melodrama, a platonic rom-com and retirement village murders: what to watch in September

James Birt does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The Conversation

The Conversation

Rotten Tomatoes

Rotten Tomatoes CNA Entertainment

CNA Entertainment TIME

TIME CNN Business

CNN Business Breitbart News

Breitbart News Fox 11 Los Angeles Sports

Fox 11 Los Angeles Sports The Babylon Bee

The Babylon Bee AlterNet

AlterNet Cover Media

Cover Media The Week

The Week