Once a haven for flamingos, sturgeon and thousands of seals, fast-receding waters are turning the northern coast of the Caspian Sea into barren stretches of dry sand. In some places, the sea has retreated more than 50km. Wetlands are becoming deserts, fishing ports are being left high and dry, and oil companies are dredging ever-longer channels to reach their offshore installations.

Climate change is driving this dramatic decline in the world’s largest landlocked sea. Found at the boundary between Europe and central Asia, the Caspian Sea is surrounded by Azerbaijan, Iran, Kazakhstan, Russia, and Turkmenistan, and sustains around 15 million people.

The Caspian is a hub for fishing, shipping, and oil and gas production, and is of rising geopolitical importance as it sits where the interests of global superpowers meet. As the sea shallows, governments face the critical challenge of maintaining industries and livelihoods, while also protecting the unique ecosystems that sustains them.

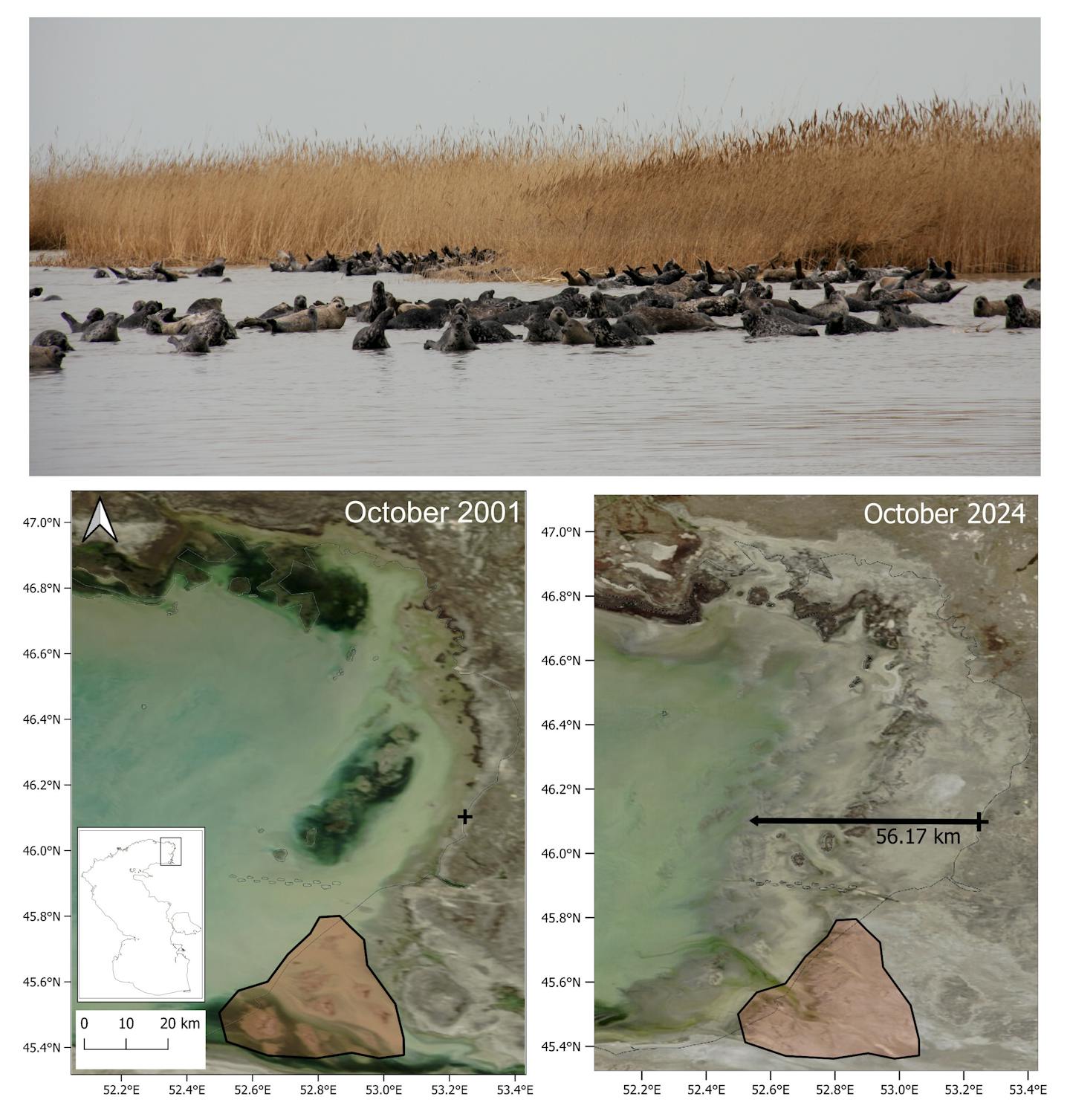

I’ve been visiting the Caspian for more than 20 years, working with local researchers to study the unique and endangered Caspian seal, and support its conservation. Back in the 2000s, the far north-eastern corner of the sea was a mosaic of reed beds, mudflats and shallow channels that teemed with life, providing habitats for spawning fish, migrating birds, and tens of thousands of seals that gathered there to moult in the spring.

Now these remote wild places we visited to catch seals for satellite tracking studies are dry land, transitioning to desert as the sea retreats, and the same story is playing out for other wetlands around the sea. This experience parallels that of coastal communities, who year by year are seeing the water recede away from their towns, fishing wharves and ports, leaving infrastructure stranded on newly-dry land, and the people fearful for the future.

A sea in retreat

The level of Caspian Sea has always fluctuated, but the scale of recent change is unprecedented. Since the turn of the current century, water levels have declined by around 6cm per year, with drops of up to 30cm per year since 2020. In July 2025, Russian scientists announced the sea had dropped below the previous minimum level recorded during the era of instrumental measurements.

During the 20th century, variations were due to a combination of natural factors and humans diverting water to use for agriculture and industry, but now global warming is the main driver of decline. It might seem inconceivable that a body of water as large as the Caspian could be at risk, but in the hotter climate the rate of water entering the sea from rivers and rainfall is reducing, and is now being outstripped by increased evaporation from the sea surface.

Even if global warming is limited to the Paris agreement target of 2°C, water levels are predicted to fall up to ten metres compared to the 2010 coastline. With the current global trajectory of greenhouse gas emissions, the decline could reach 18 metres, which is about the height of a six-storey building.

Because the northern Caspian is shallow – much of it only around five metres deep – small decreases in depth mean huge losses of area. In recent research, colleagues and I showed that even an optimistic ten-metre decline would uncover 112,000 square kilometres of seabed – an area larger than Iceland.

What’s at stake

The ecological consequences would be dramatic. Four out of ten ecosystem types unique to the Caspian Sea would disappear completely. The endangered Caspian seal could lose up to 81% of its current breeding habitat, and Caspian sturgeon would lose access to critical spawning habitat.

As in the Aral Sea disaster, where another massive lake in central Asia almost entirely disappeared, toxic dust from exposed seabed would be released, with serious health risks.

Millions of people are at risk of displacement as the sea recedes, or face highly degraded living conditions. The sea’s only link to the global shipping network is through the delta of the Volga River (which flows into the Caspian) and then via an upstream canal to the Don River for connections to the Black Sea, Mediterranean and other river systems. But the Volga is already struggling with reduced water depth.

Ports like Aktau in Kazakhstan and Baku in Azerbaijan need dredging just to keep operating. Similarly oil and gas companies are having to dredge long channels to their offshore facilities in the north Caspian.

Already the costs of protecting human interests are in the billions of dollars and are only set to grow further. The Caspian is central to the “middle corridor”, a trade route linking China to Europe. As water levels fall, shipping loads must be reduced, costs rise, and settlements and infrastructure risk being stranded tens or even hundreds of kilometres from the sea.

A race against time

Countries around the Caspian are having to adapt, relocating ports, and dredging new shipping lanes. But these measures risk conflicting with conservation goals.

For instance, there are plans to dredge a major new shipping channel across the “Ural saddle” of the north Caspian. But this is an important area for seal breeding, migration and feeding, and will be a vital area for the adaptation of ecosystems as the sea recedes.

Since the rate of change is so rapid, traditional fixed boundary protected areas risk becoming obsolete. What’s needed is an integrated, forward-looking approach to planning across the whole region. If the areas ecosystems will need to adapt to climate change are mapped and protected now, planners and policy makers will be better able to ensure future infrastructure projects avoid or minimise further damage.

To do this Caspian countries will have to invest in biodiversity monitoring and planning expertise, all while coordinating action across five different countries with different priorities.

Caspian countries are already recognising the existential risks, and have begun to form intergovernmental agreements to address the crisis. But the rate of decline may outstrip the pace of political cooperation.

The ecological, climatic and geopolitical importance of the Caspian Sea means its fate ultimately matters far beyond its receding shores. It provides a key case study in how climate change is transforming major inland water bodies across the world, from Lake Titicaca to Lake Chad. The question is whether governments can act fast enough to protect both the people and nature of this rapidly changing sea.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Simon Goodman, University of Leeds

Read more:

- The Caspian Sea is set to fall by 9 metres or more this century – an ecocide is imminent

- Volgograd: how a dam on the mighty Volga almost killed off the caviar fish

- Humans drained the Aral Sea once before – but there are no free refills this time round

Simon Goodman has provided advice to the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) on Caspian seal conservation, and in the past has conducted research and advised oil and gas companies in the Caspian on how to minimise their impact on seals. His recent work was not funded by or linked to industry. He is co-chair of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) pinniped specialist group.

The Conversation

The Conversation

America News

America News Bozeman Daily Chronicle

Bozeman Daily Chronicle Reuters US Top

Reuters US Top The Daily Sentinel

The Daily Sentinel KLCC

KLCC KNAU

KNAU The Week

The Week The radio station 99.5 The Apple

The radio station 99.5 The Apple