This month, the board of Melbourne University Press (MUP) announced it would abruptly discontinue 85-year-old Australian literary journal Meanjin. The reasons? “Purely financial.”

Our research considers the value of local books and writing, using measures other than money. Drawing on recent arts and cultural value scholarship, we’ve taken a closer look at publicly available data on Meanjin.

We drew on three broad dimensions of value articulated in the most recent Creative Australia National Arts Participation Survey. They are skills, jobs and economic prosperity; building social cohesion and equity; and wellbeing (in particular, truth-telling and participation).

We estimate the journal has provided more than 10,000 individuals with literary workforce skills, helping to train generations of leading Australian writers and editors. We tracked how a 1972 Peter Carey short story has been republished over 50 years, enabling it to be taught in schools and universities. And as Tony Birch powerfully argues, Meanjin has nurtured First Nations writers and contributed to truth-telling.

In creating our modest accounting snapshot of the broad cultural value of Meanjin, we drew on several sources. They include publicly available research reports, annual reports, indexes and bibliographies, the Meanjin website, reader responses, reader and contributor testimonies, and scholarly literature.

Tracing one story’s impact

When schools and universities use Australian writing in their teaching, students imbibe distinct local culture, demographics and geography. This plays a significant role in their learning, development and education.

We tracked the journey of some of the individual creative works first published in Meanjin, which have gone on to have a visible impact.

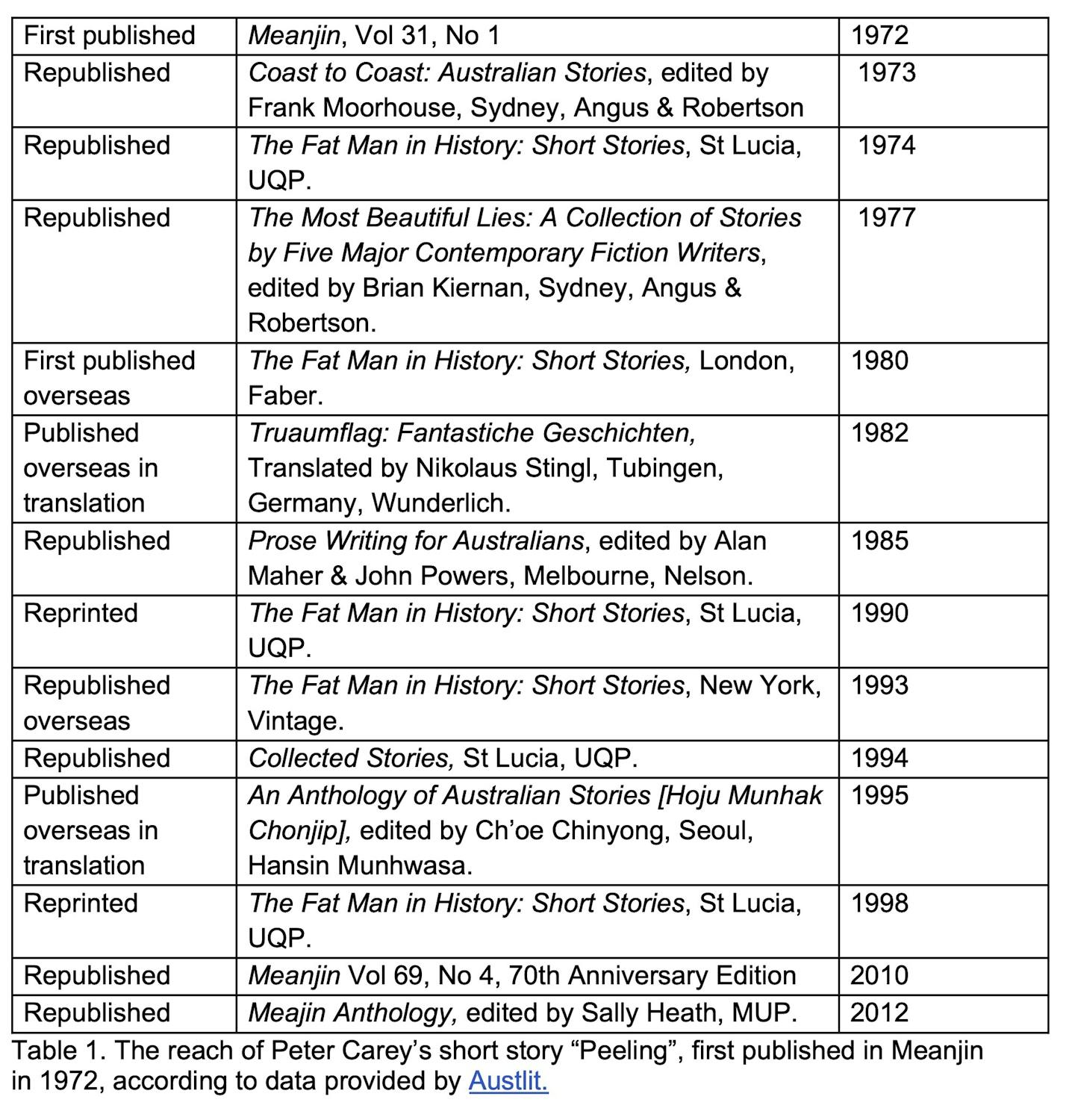

One is Peeling, a short story by Peter Carey first published in Meanjin in 1972. Data from Austlit shows it has remained in print for more than 50 years. It has appeared in anthologies and collections well known to Australian high school and university students and their teachers, and reached readers in English and other languages internationally.

Peeling has also been the focus of numerous scholarly works, both within Australia and overseas. It has also stimulated new creative works by others. In 2021, for instance, it inspired a poem by emerging writer Clare Millar in Voiceworks, a literary journal for writers under 25.

Community, debate and truth-telling

Creative place-making happens when arts and cultural institutions are integrated into cities or towns – where they connect with residents and foster civic pride.

Meanjin has been housed in MUP’s Carlton office. It’s a short walk from other significant literary institutions that have helped make Melbourne a a UNESCO City of Literature: the Wheeler Centre, the State Library of Victoria, and others. This local community is mobilising now, in an attempt to reverse the MUP board’s decision to close Meanjin down.

Meanjin has an extraordinary record for contributing to public debate on complex and controversial matters important to the social fabric of Australian life. These include essays on the health of our democracy, abortion, the new “normal” under climate crisis, police violence and our complex relationship with Pacific neighbour Nauru.

Just one example is race and racism in Australia. A quick search of Meanjin’s archives revealed more than 100 essays, reviews and interviews on the subject.

From just the past five years, they include Daniel Nour’s review of Ghassan Hage’s The Racial Politics of Australian Multiculturalism, Thomas Mayo’s thoughtful essay on the 2023 referendum, Jenny Hocking on 50 years of Australia’s Racial Discrimination Bill, and Randa Abdel-Fattah’s 2020 essay The Great Palestinian Silence, in which she asked: “What does anti-racism as practice … actually mean?”.

Esther Anatolitis, editor of Meanjin from October 2022 until its recent closure, introduced a Cultural and Literary Advisory (or, editorial advisory board) that included “at least two Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people” and supported her decision-making around First Nations matters.

In 2024, First Nations writers represented 8% of contributors – roughly double the percentage of Australia’s First Nations population (3.8%) recorded at the last census.

Tony Birch, the University of Melbourne’s current Boisbouvier Chair in Australian Literature, has explicitly recognised the journal’s valued role in supporting truth-telling.

In a statement about its proposed closure, he called it “a major supporter of Blak writers and artists in Australia”. Without it, he said, “many of us would not have been able to publish as emerging writers and may not have gone on to have a publishing life at all”.

The final report of the Yoorrook Justice Commission, Australia’s first formal truth-telling inquiry, recognised “culture supports good health and wellbeing” and that truth-telling is fundamental to reconciliation and justice.

Boosting literary skills – and jobs

Many significant Australian writers published in Meanjin’s pages early in their careers.

One of those is celebrated writer and cultural historian Maria Tumarkin, who published her first piece of literary writing in Meanjin in 1999. Axiomatic, her fourth book, was named one of the Best Books of 2019 by the New Yorker; she is one of only a handful of Australians to have been awarded the prestigious international Windham-Campbell Prize for Literature.

Award-winning writer and poet Fiona Wright published an essay that later became a centrepiece of her first book, Small Acts of Disappearance, in Meanjin. She said it helped her believe in the book she was writing.

Book industry professionals, too, have built workforce skills through Meanjin. Nicola Redhouse, a writer and editor who has professionally proofread hundreds of books for Australia’s leading trade publishers, recently reported gaining her first-ever paid editorial work at the journal, after serving as a repeat volunteer under Ian Britain.

Legendary Australian editor Hilary McPhee, cofounder of independent publisher McPhee Gribble (whose books included Helen Garner’s debut novel, Monkey Grip), acknowledged how her early work with Clem Christesen on Meanjin taught her to be an editor.

We counted the number of creatives and publishing industry professionals involved in contributing to Meanjin, sampling one volume (four issues) per decade, from 1954 to 2024.

We found, on average, 34 writers contributed to each issue, along with 12 publishing professionals. If we extend this average over the full 340 issues of Meanjin, we estimate it has provided more than 10,000 people (11,560 writers and 1,020 publishing professionals) with literary workforce skills since its first edition in 1940.

This estimate takes into account, of course, that some writers will have been published in Meanjin multiple times and most editors of the journal will have worked across multiple issues. Fiction and poetry editors, proofreaders and volunteers changed more often.

Fostering a community of readers

The most recent National Reading Survey tells us 77% of Australian readers believe it’s important to support Australian writers, and 68% like to read books by Australian writers and illustrators. As we’ve shown, Meanjin has been crucial to supporting Australian writers for 85 years.

Evidence of qualitative engagement with Meanjin by readers can be found on reader-led online platforms such as Goodreads. Here, one reader reflects on “wandering through” the Spring 2021 edition “reflecting on history and dispossession”.

Another describes reading a James Bradley essay on climate-related bushfire during the Black Summer of 2019–20. An “absolutely eerie reading experience”, it helped them process their own intense feelings of climate grief as they inhaled smoke-filled air.

Writer and critic Declan Fry won the 2023 Hilary McPhee award for his essay on Australian cultural critic McKenzie Wark. He described to us his first experience of reading the journal in a small regional library in Kalgoorlie as a teenager.

In Meanjin, he recognised something of the kind of writing he would like to one day produce, he said. He also saw the kind of literary and critical community he might like to participate in – and eventually belong to.

But to fully appreciate Meanjin’s value, we need a larger-scale project of this kind. Meanjin – and the communities it serves – deserves an accessible, comprehensive report of its public value.

Journalist Nick Feik has reported MUP commissioned an independent organisational review into Meanjin from arts, cultural and nonprofit consultant Kate Larsen earlier this year. But it was reportedly focused on structural and organisational matters – and did not recommend closing the journal.

All arts and cultural value reporting has its limitations. But it’s time to properly recognise forms of value beyond price. What’s more, assessments of broader cultural value need to be routinely accessible and visible, to a broad range of stakeholders.

Our National Cultural Policy – Revive acknowledges the importance of robust data for understanding, tracking and measuring the arts sector’s value and impact. And yet, until comprehensive public value data is routinely enabled and supported, our most treasured arts organisations and institutions will remain vulnerable to decision-making informed entirely by a single value dimension: money.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Julienne van Loon, The University of Melbourne; Bronwyn Coate, RMIT University, and Millicent Weber, Australian National University

Read more:

- A ‘thoroughly white’ novel of national mythmaking: Peter Carey’s True History of the Kelly Gang at 25

- Victoria is on the cusp of signing a Treaty with Indigenous people. It could change lives

- The decision to close Meanjin misunderstands its wider importance. Australian culture deserves better

Julienne van Loon is a member of the Australian Society of Authors, Writers Victoria and the Australasian Association of Writing Programs. She is also a board member of the Small Press Network.

Millicent Weber receives funding from Australian Research Council Discovery Early Career Research Award DE240100466, 'Audiobooks and Digital Book Culture'.

Bronwyn Coate does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The Conversation

The Conversation

Essentiallysports Combat Sports

Essentiallysports Combat Sports Political Wire

Political Wire VARIETY

VARIETY NBC 5 Dallas-Fort Worth Entertainment

NBC 5 Dallas-Fort Worth Entertainment FOX News Videos

FOX News Videos Essentiallysports Golf

Essentiallysports Golf Reuters US Top

Reuters US Top Reuters US Business

Reuters US Business Essentiallysports Olympics

Essentiallysports Olympics OK Magazine

OK Magazine