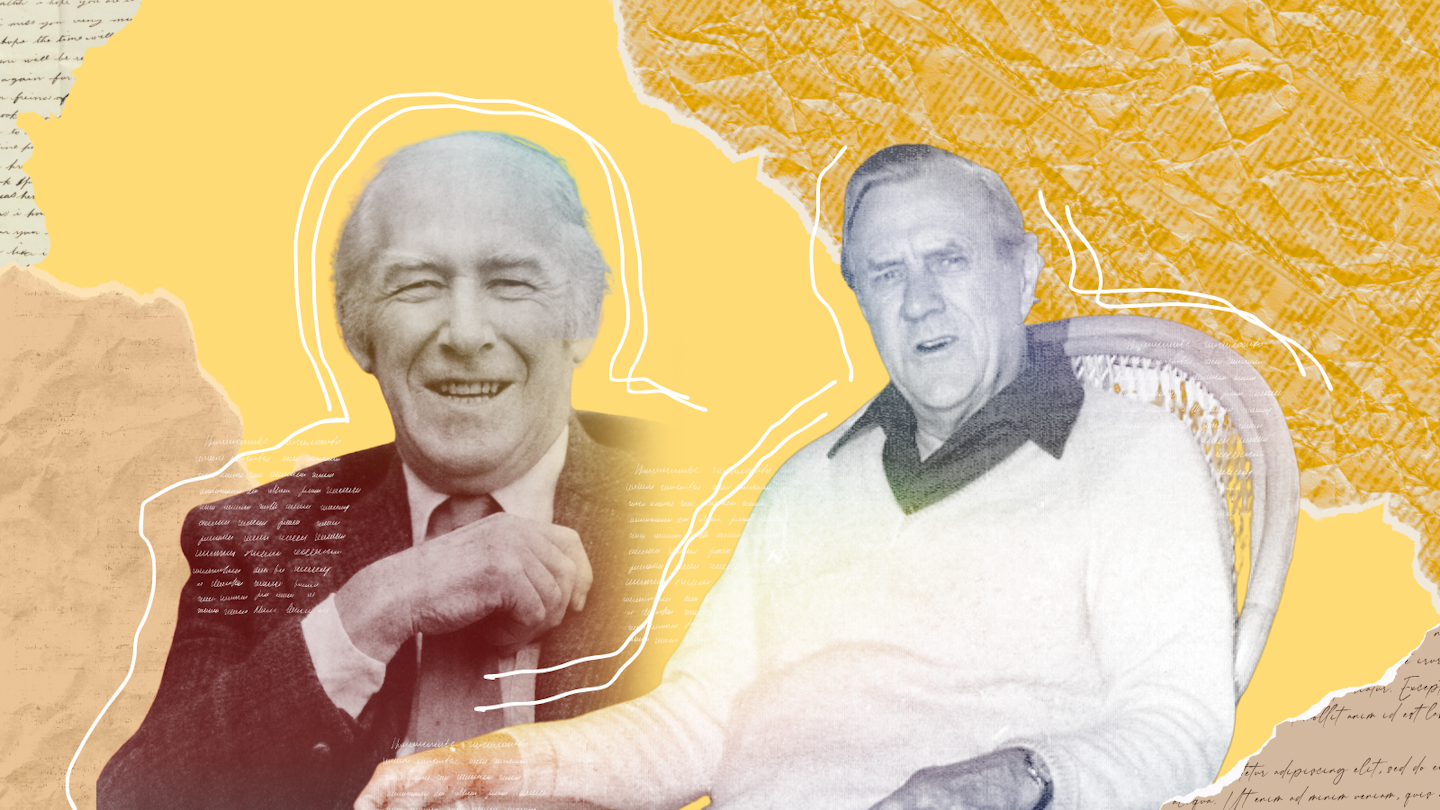

A.D. Hope and Patrick White are towering figures of 20th-century Australian culture. Few cast larger literary shadows over the postwar period. White, with his dizzying, monumental novels and Nobel prize, holds pride of place. But Hope, as a critic, poet and academic, exercised a considerable influence over his generation. His formidable intellect and commanding sense of language and poetic tradition imbued his judgements with the quality of an almost divine law.

Famously, in his review of White’s novel The Tree of Man, Hope described the writing as “pretentious and illiterate verbal sludge”. That particular judgement has not aged well.

Review: A.D. Hope: A Literary Friendship – David Brooks (Brandl & Schlesinger); On Patrick White’s Dilemmas: A Personal Essay – Vrasidas Karalis (Brandl & Schlesinger)

In quick succession, Brandl & Schlesinger, most well known as a publisher of poetry, has produced books on Hope and White. With their matching austere covers, these two books suggest a series, reminiscent of Black Inc.’s successful Writers on Writers. Like that series, these books adopt an intimate stance. They are written in a confessional style that typifies the current vogue for the personal essay.

Indeed, Professor Vrasidas Karalis subtitles his book On Patrick White’s Dilemmas “a personal essay”. By this, he means to signal that he will explore not just the works of the famous Australian writer, but how they have affected him.

The early part of the book describes how Karalis came to fall in love with White’s novels. Australia seemed a mythical place to Karalis when he was growing up in provincial Greece in the early 1970s, not least because whole villages had migrated to those antipodean shores over the previous decades. At a young age, he stumbled on a Greek translation of White’s novel The Tree of Man. He tried to read it to his grandmother, but neither could make head or tail of it. She asked for something else.

Then, as a graduate student in the Netherlands, Karalis came across a pile of White’s books being remaindered:

There and then, in the remainders section, in an existential impasse, in the freezing cold of the European north, I re-entered Patrick White’s world, and a lifelong romance began.

There is a symmetry here, since White had a lifelong romance with Greece, reflected in his enduring relationship with Manoly Lascaris. Karalis’s earlier book Recollections of Mr Manoly Lascaris (2007) was based on a friendship he formed with Lascaris in his later years, after the death of White. This Greek connection to White is also visible in Christos Tsiolkas’s monograph on White for the Black Inc. series. In fact, it is a little surprising that Karalis makes no mention of Tsiolkas’ book in Patrick White’s Dilemmas.

Karalis attempts to place White on a new critical footing. Here is where things go a little awry. Many of Karalis’s claims are suggestive. They have a brash hyperbole that at least marks a change from the more pinched academic formulations he rails against. His preference is for the declarative aphorism:

White writes as if he doesn’t really know what is happening in his narratives, or indeed his own mind.

Or again:

His characters are always at a dead-end; they confront their own limitations which they cannot surpass or deepen.

Or again:

White presents a fundamental disagreement between the narrative and the narrator: he turns one against the other.

The ethos of the book, however, does not offer concerted reasoning for these epigrams or tease out their implications.

Where things really start to totter, though, is when Karalis moves beyond White’s novels into more general opinions. The vehemence of these views seems to far exceed the need of the moment. At one point, Karalis takes aim at the way the Reformation ruined Western civilisation:

Wretched sinners in the hands of an angry God, Protestantism is probably the most narcissistic exhibitionism of self-aggrandisement that any religion has ever promulgated.

This tradition, we are told, links directly to “the puritans and the zealots of political correctness”, who have in turn laid waste to the honourable creativity of contemporary times.

The book purports to rescue White from the clutches of such cardboard villains. But as it continues, one more and more gains the impression that the opposite is true: the novels of White are being used as cover for the author’s jeremiads.

There is marked lack of critical generosity. While David Marr’s monumental biography of White also goes unmentioned, Karalis devotes several pages to excoriating a study of White’s fiction by literary scholar Simon During. He claims During’s book destroyed “the possibility of any informed and fair reading of White’s novels” – adding, after a pause, “and probably, of all novels from the past”.

These off-the-cuff derogations make it difficult to take seriously the claims that Karalis makes about White’s writing.

A literary friendship

It is some relief then that, outward appearances aside, David Brooks’s book on A.D. Hope is an altogether different beast. It tells the story of the “literary friendship” that Brooks maintained with Hope over many years.

The particular form of this friendship was that of mentor and protégé. Brooks studied under Hope as an undergraduate at ANU in the mid-1970s, part of a coterie of young poets that also included Kevin Hart, Alan Gould and Philip Mead.

Hope was nearly half a century older than these students. His arch-classicism sat uneasily with the radical currents of poetry that came out of late-1960s Australia. Yet Brooks found himself drawn to Hope’s circle, and Hope took him under his wing.

In many ways, one can read Brooks’s account as a story of patronage. The concept comes with certain cynical associations, but what we see detailed are the nuances and subtleties of the relationship between a master and his follower. What makes the book compelling is Brooks’s high degree of self-awareness about these intricacies. His narration adopts a wistful, almost insouciant tone. Yet we also find this long relationship, seemingly the defining creative relationship in his life, subjected to a searching examination.

Brooks became Hope’s editor, which he describes as “a complicated and complicating role”:

I not only saw him fairly regularly, knew him as a friend, knew his friends, was part of a common circle, etc., but I spent a great deal of time – overall, I suppose, it would add up to a year or two of my working life – sitting with his poems and other writings, going through them line by line, over and again, as I typed them, proof-read them, sought to understand them, as if these things can ever be separated.

This paratactic style of writing, in which clauses stack gently upon one another in long undulating sentences, lends a Proustian quality to Brooks’s recollections. His understated style stands in stark contrast to Karalis’s bombast.

What Brooks captures is the particular ambivalence of the acolyte. On the one hand, he has been invited into the master’s inner world, made privy to the secrets of the life beneath the grand public visage. On the other hand, he must always approach this knowledge from the position of the conscientious supplicant. This helps account for the peculiar combination of politeness and resentment that the story of this friendship reveals. There is a continuous sense of complicit trespass, as if he were Goldilocks in the home of the three bears:

I’d lived in his house while he was away. I’d slept in his bed when he wasn’t there. It must have seemed, sometimes, though I don’t think I ever was intrusive, or anything but disrespectful, as if I was tracking him, scrutinising him.

This element of intrigue, of not-quite-accidental eavesdropping, extends to every element of the friendship. It inflects the way Brooks reads his master’s work:

As I went over it line-by-line, as I combed through it, as I stopped, thought, looked around, asked questions of it, tried to get its meaning straight, I would see things, catch whispers, sighs, just as [Hope] says of the freshly-opened vault in [his poem] ‘A Visit to the Ruins’.

The other stylistic influence on Brooks’s fascinating book is the German writer W.G. Sebald. This is evident not just in the incidental photographs that fleck the often oneiric reveries with the grain of reality, but in the slightly quizzical way the fundamental epiphanies take place.

Brooks replays the moments of this defining relationship as if they were open to doubt: “Was Alec afraid I was seeing, interrogating, things that he did not want looked into – that even he himself, perhaps, did not want to approach too closely?”

The whole book transpires beneath this perpetual “perhaps”. What is clear, though, is that this “perhaps” is less a signifier of uncertainty than of devastating finality. The book has the final say: it is the acolyte’s last laugh. The greatness of Hope falls into the vortex of the master’s lack, in a way reminiscent of philosopher Raimond Gaita’s exquisite eulogy Romulus, My Father. The father’s dignity is perpetuated, but against the grain of his undoubted failings.

We will not have to wait long for a rather different account of Hope’s life. Susan Lever will soon publish her biography of Hope. This will not have the same complicated complicity that Brooks’s book carries in its bosom. His book has a beautiful partiality. It reminds me of Paul Auster’s New York Trilogy or more recently, Susanna Clarke’s Piranesi, both of which are studies of anguished discipleship. Like these writers, Brooks offers a poetic testament to the acolyte’s revenge.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Tony Hughes-d'Aeth, The University of Western Australia

Read more:

- Greg Sheridan thinks the early Christians have lessons for today’s faithful – is he right?

- Alexis Wright has revitalised Australian literature, but a new book by a ‘superfan’ overlooks an important aspect of her work

- Wealthy, whiny and wildly tone deaf: Elizabeth Gilbert’s new memoir exemplifies ‘priv-lit’

Tony Hughes-d'Aeth has recieved funding from the Australian Research Council.

The Conversation

The Conversation

People Books

People Books Slate Culture

Slate Culture TODAY Pop Culture

TODAY Pop Culture Los Angeles Times Arts

Los Angeles Times Arts AZ BIG Media Lifestyle

AZ BIG Media Lifestyle CNN Business

CNN Business Ann Arbor News Life

Ann Arbor News Life Esquire

Esquire