One spring, after a long winter, an aged elephant lay dying at the bank of a small stream near the coast of what is now northern Italy. Soon after, some scavengers arrived to dine on this huge stockpile of food.

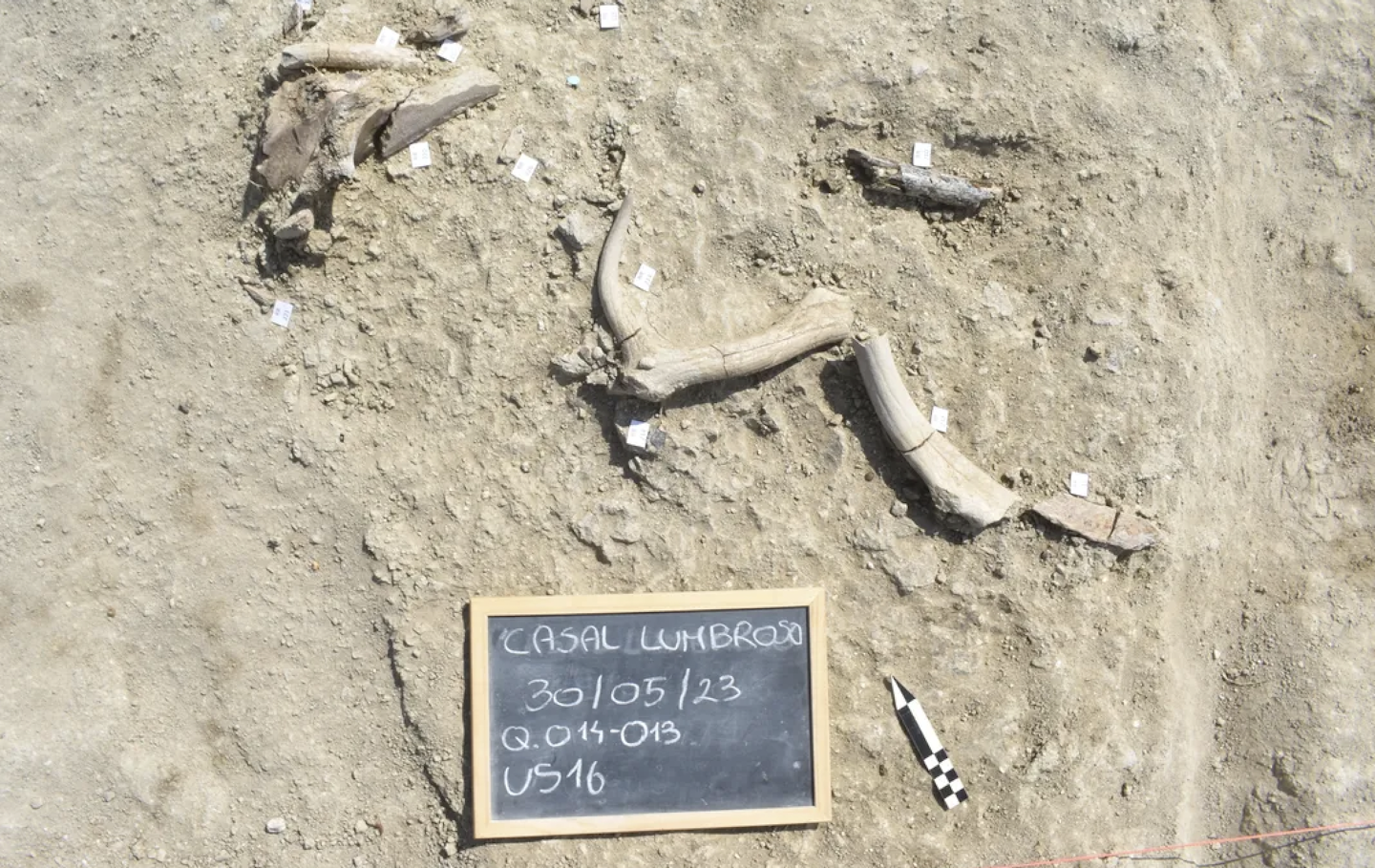

Over 400,000 years later, building activities at Casal Lumbroso on the outskirts of Rome have revealed one of the elephant’s tusks, prompting archaeological excavations to investigate the immediate surroundings.

A newly published study, led by Enza Spinapolice and Francesca Alhaique, not only provides an insight into the death of the elephant but also, perhaps more interestingly, the lives of the scavengers that fed on it.

These scavengers were no hyenas. They were a strange species of primate walking on two legs – early nomadic humans, living in Europe at a time long before people built houses or even lit fires, who briefly halted to profit from this unexpected windfall.

This discovery is a successful example of how archaeological heritage management can be integrated within development and building activities. Since 1992, a European-wide treaty makes it compulsory for EU nations to protect their archaeological heritage. But each country can decide for itself how to do so.

In my native Netherlands, the discovery of an animal fossil alone would not necessarily lead to excavations. A site like this might therefore easily be destroyed unseen.

But in the elephant’s case, the Roman archaeological superintendence went beyond the call of duty. They organised an ambitious research project which revealed – and solved – a tantalising puzzle of early human behaviour: what exactly did these nomadic scavengers do with the body of this animal?

Solving a 400,000-year-old jigsaw

Four hundred thousand years ago, humans in Europe were few in number but probably most common along the Mediterranean shores. Their fossils are extremely rare, but skulls from Sima de los Huesos (literally meaning “pit of bones”) in northern Spain and Swanscombe in England show that the people around this time were early Neanderthals.

Luckily for us, they left behind more than just their skeletons. We can also study their tools, which have been recovered across large parts of Europe – as far north as the south of England.

The river in which the Casal Lumbroso elephant died transported ash from a volcanic eruption that can be precisely dated to 404,000 years ago – so the elephant must have died after this. But the position of the sediments shows the ash deposits were from a warm period, dating to before 395,000 years ago. From that time, colder conditions started prevailing.

So, this puzzle for archaeologists was laid down in a very narrow (from an archaeological point of view) time slice.

In these warm periods, Italy was inhabited by a fascinating community of animals including wolves, lions, hyenas, hippos and rhinos. But straight-tusked elephants were the crowning glory. This species was much larger than an African elephant and was a true ecosystem engineer, opening up landscapes that would otherwise be densely forested, improving productivity for many other species.

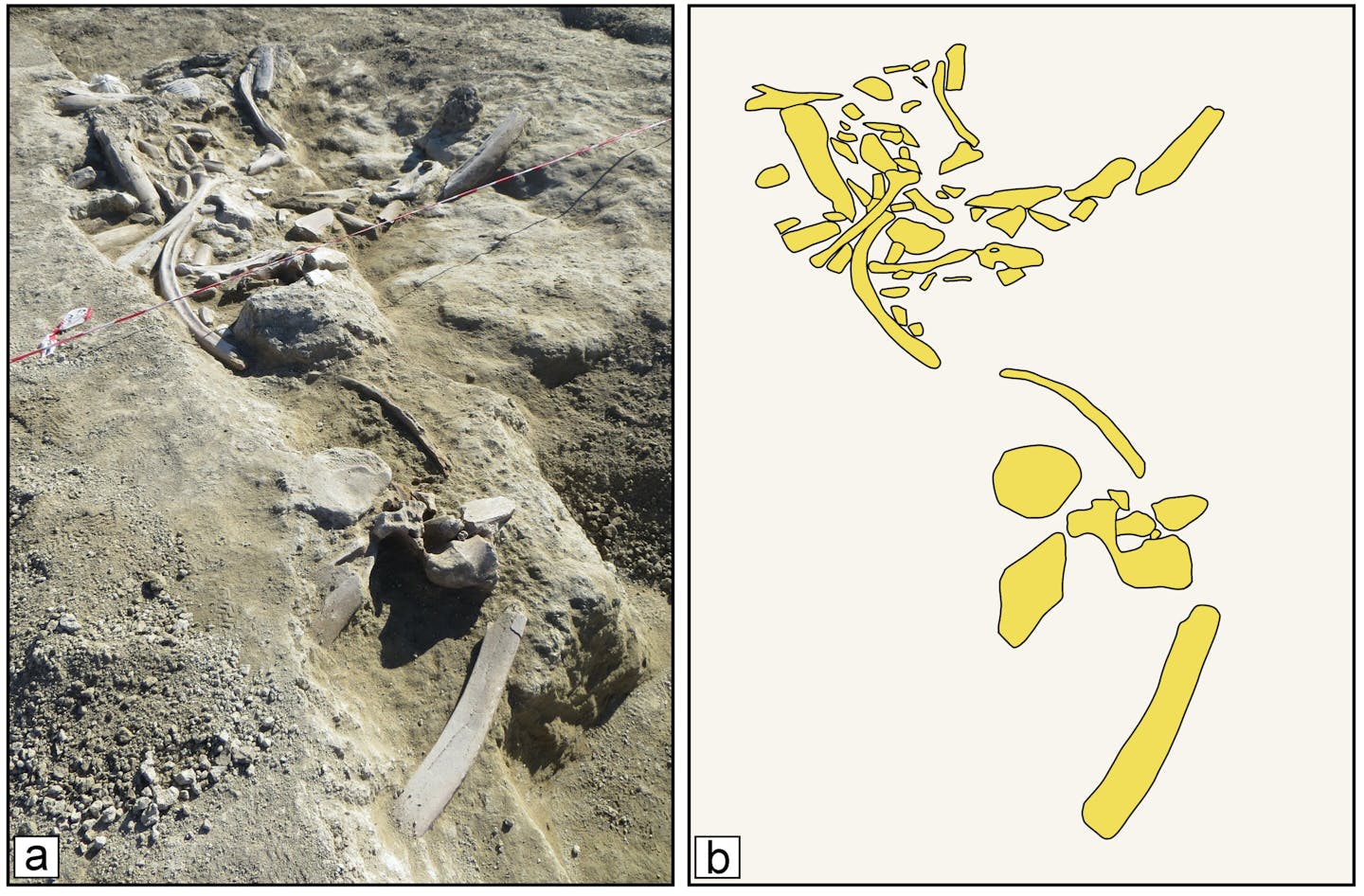

This particular animal was in its late 40s – old for an elephant. It may have gotten stuck in the mud of the riverbank and died a natural death. We know this happened in other places too – for example, at Pogetti Vecchi in Tuscany, where seven elephants died in a hot spring and were later partially butchered. At Casal Lumbroso, we even know the season in which the elephant died: shed red deer and fallow deer antlers suggest it was spring.

Humans roaming the landscape in small groups would naturally be attracted to this mountain of meat. While the bones of the elephant do not show characteristic cut-marks produced by slicing and filleting, they do show hammer marks and were found next to several small flint tools.

We can see that the people hammered open some bones, perhaps for the fat marrow inside. But they also used the bones to make tools. This is uncommon behaviour which has only been documented at a few other sites.

In most cases, it seems the early Neanderthals preferred to make their tools from flint and, we suspect, other materials such as wood that are only rarely preserved for us to find. Creating bone tools is sometimes seen to be a technologically complex behaviour, indicating modern-like intellect.

I think the explanation is simpler: we rarely find them because they are more likely to decay than stone tools. Their use in at Casal Lumbroso may have been a case of “needs must”.

After all, beautiful though the ancient Italian environment may have been, for people depending on good stones for their tools, it had a severe shortcoming: flint was only available in very small pebbles.

These humans’ technology was nowhere near as sophisticated as the “classic” Neanderthals of later times who distilled birch tar, gave stone tools wooden handles and routinely lit fires – all of which we do not see this far back in time. This group was versatile enough to modify their technological repertoire to produce very small flint tools, but also to explore using other materials like elephant bone.

They adapted to the small flint pebbles using “bipolar technology” – a technique already in evidence at the first archaeological site, 3.3 million-year-old Lomekwi in Kenya. It consists of putting the stone you want to flake on a larger stone anvil, then hitting it at the top with another stone. This splits the pebbles into two pieces and from here, sharp flakes can be produced.

Some of the flint tool edges found at Casal Lumbroso were pristine enough to analyse for microscopic traces of their prehistoric use. They point to use on a rather soft material, which could mean the cutting of elephant meat – although this could be caused by other things as well.

These early Neanderthals also had more complex technical repertoires. They brought a hand axe to the site, made on (and from) a larger block of limestone – not the best material for tools as it is quite soft, but still suitable to make this larger tool type.

Possessing only imperfect stones – either too small or too soft – this group also grasped the potential of the huge elephant bones to fashion into tools. They broke up some bones and shaped them by flaking the bone with a hammerstone, in the same way they worked flint.

For perhaps only a few hours, the sounds of flint hitting the anvil, the cracks of breaking bone and the excited shouts of people flushed with a rich source of food would have filled the air. Then these early people would have moved on again, perhaps to find a suitable spot for the night.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Gerrit Dusseldorp, Leiden University

Read more:

- Why did modern humans replace the Neanderthals? The key might lie in our social structures

- Why the Neanderthals may have been more sophisticated hunters than we thought – new study

- How Neanderthal language differed from modern human – they probably didn’t use metaphors

Gerrit Dusseldorp does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The Conversation

The Conversation

CNN

CNN The Federick News-Post

The Federick News-Post WCPO 9

WCPO 9 Raw Story

Raw Story @MSNBC Video

@MSNBC Video AlterNet

AlterNet New York Post Opinion

New York Post Opinion ABC30 Fresno Sports

ABC30 Fresno Sports TMZ

TMZ