They were pregnant. Some were prisoners. Others were the poorest of the poor, forgotten in death as in life. Yet dissection and depiction of their bodies have become the foundation of anatomical teaching.

Cradled in the pages of anatomy textbooks are figures stripped bare, not only of skin but of identity. Eduard Pernkopf’s infamous Nazi-era atlas contains exquisite, hyper-realistic drawings created from the bodies of political prisoners executed under Hitler’s regime.

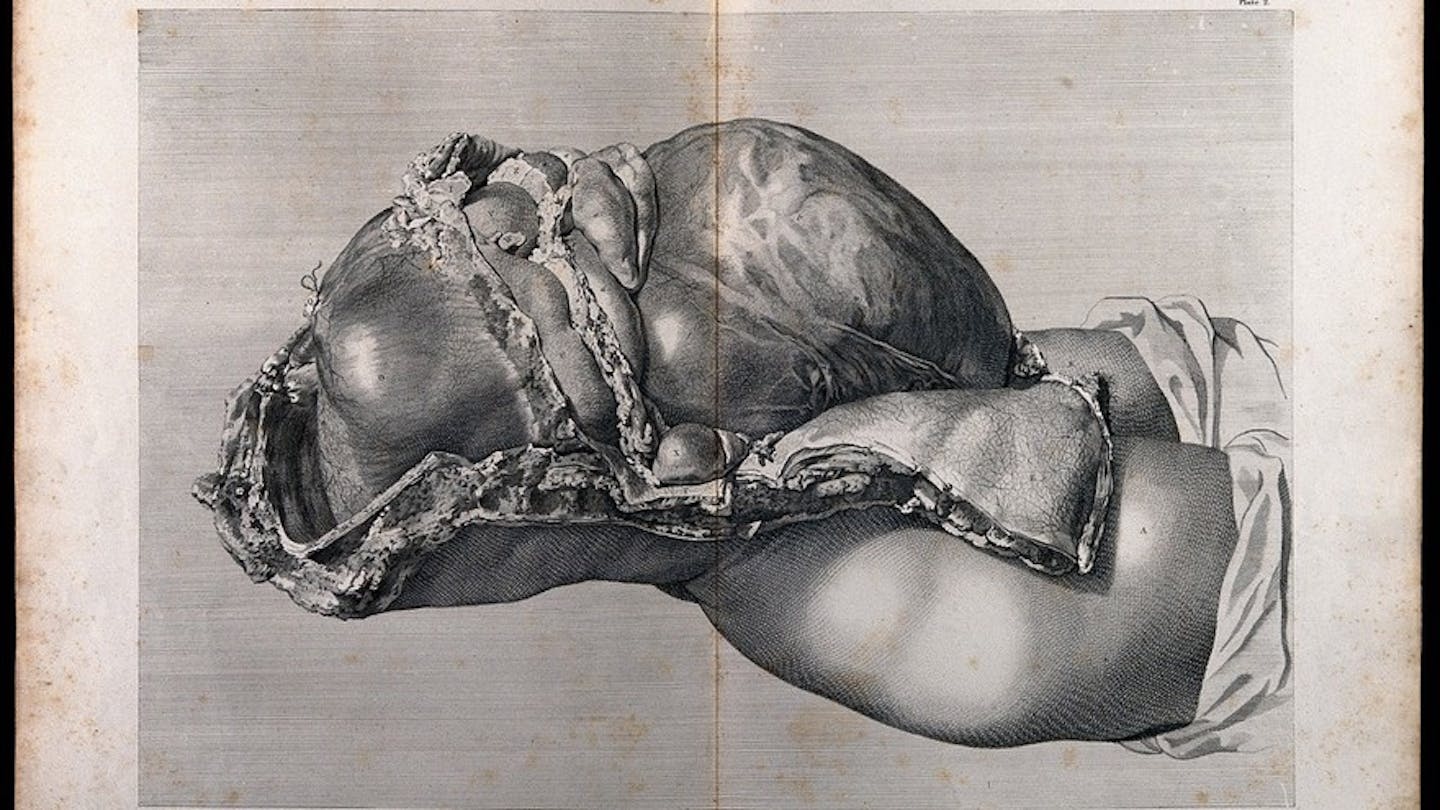

William Hunter’s celebrated The Gravid Uterus (1774) shows dissected pregnant women with clinical detachment, their swollen wombs exposed. But who were these women? How did they end up on the dissection table? And, crucially, did they ever consent? It’s something rarely considered by educators, students and the public alike.

Today, body donation is governed by clear laws and ethics. In the UK, the 2004 Human Tissue Act (2006 in Scotland) requires informed, personal consent for anatomical investigation, and further consent to be given for production of images.

Annual memorial and thanksgiving services also honour donors, and those studying anatomy are taught to treat cadavers with the same dignity they would offer the living – the medic’s first patient, albeit silent.

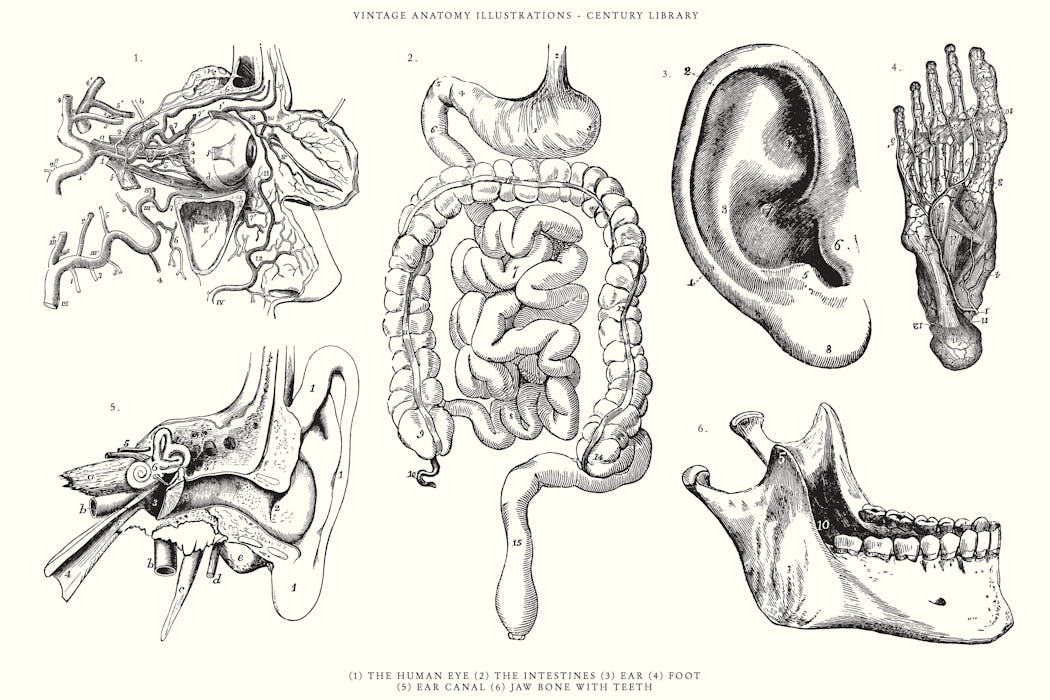

But historical anatomical illustrations, still in use across education and medicine, were produced at times long before such safeguards existed. Most texts and imagery feature people who never gave permission to be dissected, let alone depicted for eternity. Should we keep using these images? Or does that make us complicit in a long history of medical exploitation?

Anatomical illustration and, therefore, the history of the peoples depicted, mirrors the legal and cultural attitudes toward dissection at the time. The first recorded human dissections occurred around 300BC in Alexandria, Egypt. In the second century, Galen, a Greek physician, dissected animals and treated gladiators, and laid the foundations for anatomical understanding in Europe for over a thousand years.

In medieval Europe, dissection was rare and heavily ritualised, often serving theological rather than scientific purposes. By the Renaissance, anatomy began to take its modern form. Leonardo da Vinci conducted detailed dissections, producing hundreds of drawings that combined anatomical accuracy with artistic brilliance. Yet he, too, was not above questionable methods, reportedly obtaining bodies through informal deals with hospitals and executioners. The identities of his subjects remain unknown.

In 1543, Andreas Vesalius published De Humani Corporis Fabrica, challenging centuries of Galenic error with visual evidence from dissection. His cadavers, however, were idealised, muscular, often white and probably male.

In one image, a body holds back its own skin to reveal its musculature, just like Saint Bartholomew the Apostle in his martyrdom. Never before had an anatomical text been so highly illustrated. The images were groundbreaking, but they romanticised death and dehumanised the dead.

Over time, anatomical realism became the goal. In the 17th and 18th centuries, Dutch and British anatomists like Govard Bidloo and William Hunter embraced unflinching detail – depicting the morbidity of the cadaver, showing decomposition, often violent incisions, and the tools of dissection.

Hunter’s The Gravid Uterus aimed to transform obstetrics through realism. But it relied on 14 pregnant bodies whose origins remain ethically troubling.

How did he obtain them? Even though the 1752 Murder Act allowed the anatomisation of executed murderers, only a few bodies were legally available in this way, insufficient for demand. Between 1752 and 1776, just four cadavers were sourced under the Act in London.

At the time, the proportion of women dying in childbirth was also low, around 1.4%. The likelihood that Hunter’s subjects were legally obtained is slim. More likely, they were acquired through body snatching, a common but illegal practice. Their identities were never recorded. Their images endure.

Grave robbers or “resurrection men” helped meet the growing demand for cadavers – driven by the expansion of medical education and legal restrictions on supply – by targeting the poor: those buried in shallow, recent or unmarked graves at the edges of cemeteries. Wealthier people could protect their dead in gated cemeteries patrolled by paid guards, coffins protected by iron cages or in stone vaults.

The rich could buy safety even in death. The poor were left exposed, not because they lacked value, but because they lacked power.

The 1832 Anatomy Act curbed grave robbing but entrenched injustice. Unclaimed institutionalised bodies became the new legal supply, those from workhouses, poorhouses, asylums, prisons and hospitals.

Until the 1984 Anatomy Act, and more definitively the 2004 Human Tissue Act, informed consent was not required. Let’s be clear: the bodies in most anatomical images were not volunteers. They were poor, criminalised and marginalised – those who in life already suffered the most.

The most extreme more modern example is Pernkopf’s Atlas of Topographical and Applied Human Anatomy. Widely regarded as one of the most detailed and visually stunning anatomical texts, particularly in its depiction of the peripheral nerves, it is the most ethically troubling.

The atlas was created during the Nazi regime, with at least 1,300 bodies of Jewish prisoners, Roma, queer individuals and political dissidents, many of whom were executed in Vienna’s Gestapo prison.

Despite its origins in medical atrocities, the atlas remained in print until the 1990s. Even decades later, its influence persists. A 2019 study found that 13% of neurosurgeons still use the atlas.

Some defend its continued use, citing its anatomical precision, especially in complex neurological surgeries, so long as its dark history is acknowledged. Others argue that any clinical benefit is outweighed by the ethical cost, and that continued use implies endorsement of its origins.

Efforts underway

But Pernkopf is only the most dangerous example. Across many historical images, the same fundamental question arises: can medical knowledge built on exploitation ever be fully separated from it?

There’s no single solution, but there are efforts underway. Some educators are adding context in lectures, footnotes and course materials, taking time to teach the history, acknowledging who was probably depicted and under what circumstances.

Medical illustrators are creating new images based on informed consent and modern day guidelines, partly also to create diverse representation across population history, gender, body type and ability. Institutions are digitising and cataloguing old collections with proper historical notes, so they aren’t used uncritically.

But these efforts are piecemeal. There are no universal standards or regulations governing historical anatomical imagery, falling out of the remit of even the most strict governing body. Meanwhile, these illustrations circulate freely online, in textbooks, even on social media, stripped of context, divorced from their origins.

And so, the same injustices risk being quietly perpetuated. We must start by asking better questions: who is represented in anatomical imagery today? Whose bodies are missing? And whose stories are never told?

Short term, we need clear provenance research, labelling and transparency around historical illustrations. Teachers, editors and publishers must acknowledge the sources of these images, even if unknown.

Long term, we must invest in creating new, inclusive anatomical libraries that reflect the full diversity of human bodies, across gender identities, racial backgrounds, disabilities and life stages. With ethical sourcing and clear consent, we can build materials that respect the living and the dead alike.

The people in these illustrations, silent, anonymous and dissected, were never asked to teach us. But they have and now, it’s our responsibility to ask: what kind of legacy are we creating in return?

If we want medicine to be ethical, inclusive and just, it starts with the very images we learn from. It’s time to look again at the bodies behind the drawings. And this time, to really see them.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Lucy E. Hyde, University of Bristol

Read more:

- Should you be concerned about ‘overspending’ your daily heart beats?

- Vitamin B3 supplement may reduce your risk of skin cancer

- Can friendship keep you young? Scientists say your social life might slow ageing

Lucy E. Hyde does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The Conversation

The Conversation

Law & Crime

Law & Crime Associated Press Top News

Associated Press Top News Local News in South Carolina

Local News in South Carolina FOX News

FOX News Raw Story

Raw Story Reuters US Business

Reuters US Business New York Post

New York Post Cover Media

Cover Media AlterNet

AlterNet WBRC

WBRC New York Post Media

New York Post Media