A new album by Woody Guthrie (1912–1967), perhaps the most influential US folk artist, was released late last summer. Woody at Home, Vol. 1 & 2 contains songs – some already known, others previously unreleased – the artist recorded from 1951 to 1952 on a tape recorder he received from his publisher. A version of the famous “This Land Is Your Land” (1940), with new verses, is among the tracks.

The release reflects the continuing vitality of Woody Guthrie in the United States. There is an ongoing process of updating and redefining his figure and artistic legacy – one that does not always take into account the singer’s radicalism but sometimes accentuates his patriotism.

The story of “This Land Is Your Land” is a case in point. There are versions of the song containing verses critical of private property, and others without them. The first version of “This Land” became almost an unofficial anthem of the US and, over the years, has been used in various political contexts, sometimes resulting in appropriations and reinterpretations. In 1960, it was played at the Republican national convention that nominated Richard Nixon for president, and in 1988, Republican candidate George H. W. Bush used it in his presidential campaign.

However, Guthrie made his contribution by supporting both the Communist Party and, at different times, president Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal. He borrowed the idea that music could be an important tool of activism from the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) union. In the party, Guthrie saw the ideological cement; in the union, the instrument of mass organization. It was only through union – a term with a double meaning that Guthrie often played upon: union as both labour union and union of the oppressed – that a socialized and unionized world could be achieved.

‘Deportee’

The release of Woody at Home, Vol. 1 & 2 was preceded by the single “Deportee (Plane Wreck at Los Gatos),” a song that had long been known, but whose original recording by Guthrie had never been released. The artist wrote it in reference to an event that occurred on January 28, 1948, when a plane carrying Mexican seasonal workers crashed in Los Gatos Canyon, California, killing everyone on board.

This choice was not accidental, as explained by Nora Guthrie – one of the folksinger’s daughters and long-time curator of her father’s political and artistic legacy – in an interview with The Guardian, where she emphasized how his message remains current, given the deportations carried out by the President Donald Trump’s administration.

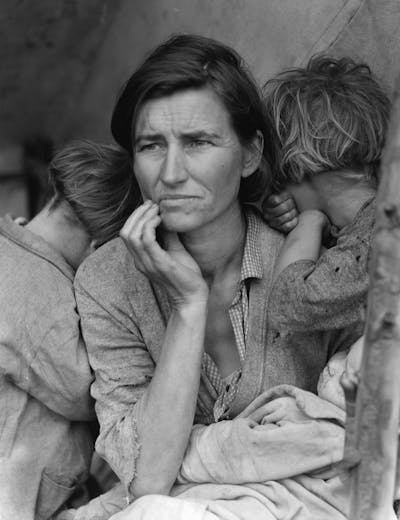

Woody Guthrie read the account of the tragic plane crash in a newspaper, and was horrified to find that the workers were not referred to by name, but by the pejorative term “deportees”. In their story, he saw parallels with the experiences of the 1930s “Okies” from the state of Oklahoma, impoverished by dust storms and years of socioeconomic crisis, who moved to California in search of a better future. It was a “Goin’ Down The Road,” according to the title of another Guthrie song, in which the word “down” also conveyed the sadness of having to hit the road, with all the uncertainties and hardships that lay ahead, because there was no alternative – indeed, the full title ended with “Feeling Bad”.

The Okies and the Mexican migrant workers faced racism and poverty amid the abundance of the fruit fields. Mexicans found themselves picking fruit that was rotting on the trees – “the crops are all in and the peaches are rotting” – for wages that barely allowed them to survive – “to pay all their money to wade back again”. In “Deportee,” in which these two lyrics appear, Guthrie provocatively asked:

Is this the best way we can grow our big orchards?

Is this the best way we can grow our good fruit?

To fall like dry leaves to rot on my topsoil

And be called by no name except “deportees”?

Visions of America and radicalism

“We come with the dust and we go with the wind,” sang Guthrie in “Pastures of Plenty” (1941, and also included in Woody at Home), the anthem he wrote for the migrants of the US southwest, denouncing the indifference and invisibility that enabled the exploitation of workers. In this way, Guthrie measured the gap separating the US’s reality from the fulfillment of its promises and aspirations. For him, tragedies were also a collective issue that allowed him to denounce the way in which a minority (the wealthy capitalists) deprived the majority (the workers) of their rights and well-being.

The artist’s political vision owed much to the fact that he grew up in Oklahoma in the 1920s and 30s, where the influence of Jeffersonian agrarian populism – the vision of an agrarian republic inspired by president Thomas Jefferson, based on the equitable distribution of land among citizens – remained deeply rooted. It is within this framework that Guthrie’s radicalism, which took shape in the 30s and 40s, must be situated. These periods were marked by intense debate over the health of US democracy, when Roosevelt’s New Deal sought to address years of economic crisis and profound social change.

Against racial discrimination

Guthrie’s activism sought to overcome racial discrimination. This was no small feat for the son of a man said to have been a member of the Ku Klux Klan and a fervent anti-communist, who may have taken part in a lynching in 1911.

Moreover, Woody himself, upon arriving in California in the latter half of the 1930s, carried with him a racist legacy reflected in certain songs – such as his performance of the racist version of “Run, Nigger Run”, a popular song in the South, which he sang on his own radio show in 1937. Afterward, the artist received a letter from a Black listener expressing her deep resentment over the singer’s use of the word “nigger”. Guthrie was so moved that he read the letter on the air and apologized.

He then began a process of questioning himself and what he believed the United States to be, going so far as to denounce segregation and the distortions of the judicial system that protected white people while readily imprisoning Black people. These themes appear in “Buoy Bells from Trenton”, also included in Woody at Home. The song refers to the case of the Trenton Six: in 1948, six Black men from Trenton, New Jersey were convicted of murdering a white man by an all-white jury, despite the testimony of several witnesses who had seen other individuals at the scene of the crime.

“Buoy Bells from Trenton” was probably included on the album because of the interpretation it invites concerning abuses of power and the “New Jim Crow”, an expression that echoes the Jim Crow laws (late 19th century to 1965) that imposed racial segregation in the Southern states. These laws were legitimized by the Supreme Court ruling Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), which established the principle of “separate but equal”, before being abolished by Brown v. Board of Education (1954), the Civil Rights Act (1964) and the Voting Rights Act (1965). Popularized by Michelle Alexander in her book, The New Jim Crow (2010), the contemporary term refers to the US system of racial control through penal policies and mass incarceration: in 2022, African Americans made up 32% of convicted state and federal prisoners, even though they represent only 12% of the US population, a figure highlighted by several recent studies.

Guthrie’s song can thus be reread as a critique of persistent racism, both in its institutional forms and in its more diffuse manifestations. Once again, this is an example of the enduring vitality of Woody Guthrie and of how art does not end at the moment of its publication, but becomes a long-term historical phenomenon.

A weekly e-mail in English featuring expertise from scholars and researchers. It provides an introduction to the diversity of research coming out of the continent and considers some of the key issues facing European countries. Get the newsletter!

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Daniele Curci, Università di Siena

Read more:

- With Riot Women, Sally Wainwright is turning menopause into punk rebellion

- What role did music play in Trump and MAGA’s electoral appeal?

- How Russia’s musicians are taking a stand against the war in Ukraine

Daniele Curci ne travaille pas, ne conseille pas, ne possède pas de parts, ne reçoit pas de fonds d'une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n'a déclaré aucune autre affiliation que son organisme de recherche.

The Conversation

The Conversation

WAND TV

WAND TV America News

America News Raw Story

Raw Story Reuters US Top

Reuters US Top The radio station 99.5 The Apple

The radio station 99.5 The Apple Action News 5 Crime

Action News 5 Crime Cover Media

Cover Media AlterNet

AlterNet MENZMAG

MENZMAG