There’s an intensity to festivals, a spillover effect where one event leads to another as if the whole town were participating in one long, articulated show.

It’s not just the proximity of multiple works in space and time. It’s the conversations, the shared experiences, and the ways in which the concerns of one work amplify or contest those of another.

While the dance works of this year’s Lyon Dance Biennale were largely European – especially French – in origin, 2025 is the “Brazil–France Cultural Year”.

Several Brazilian companies unlikely to travel otherwise were able to make their mark within the choreographic space of Europe’s largest dance festival.

‘Broken dance’

The difference of origin and resources from a European context was particularly evident in Original Bomber Crew’s Vapor, Ocupação Infiltravel (Vapor, Infiltrable Occupation).

The work uses a host of everyday, gathered materials – cardboard, plastic, tape, paint, container, wood, skateboard and shopping trolley – to create a powerful evocation of Northeastern Brazilian culture.

Cardboard is secured to create a dance floor, a shopping trolley serves as a ship’s figurehead, skateboards are used as a surface for video projection.

Vapor, Ocupação Infiltravel combines shamanistic ritual with breakdance, capoeira martial art, real-time painting, live and recorded music, sounds, and images, a style they call dança quebrada or broken dance.

Roosters crow as we watch video of motorbikes travelling gravel roads. The dancers are strong and loose, each moving in their own way, individual but together.

Two performers paint a large fish on a cardboard wall, improvising layer upon layer of colour and shape. Another writes on the floor, while the musical composer enters the space to beat a makeshift, plastic drum.

Although myriad activities occur simultaneously, the group functions as a precisely organised whole. Dancers run the gamut then gather to form tableaux, snapshot formations, and serial processions.

The air is thick with sensation, offering an intimate feeling of place, community and culture. The end of the work is achieved with a group embrace, an expression of communal connection later extended to all and sundry.

A living monument

Dance has this capacity to create a form of community between the group, offering a mode of social experiment through movement.

Eszter Salamon’s Monument 0.10, The Living Monument, commissioned by Norway’s national company Carte Blanche, is a two-hour work consisting of a series of slow-moving group formations, barely discernible in low light.

Staged in a large theatre space, the feeling is historic: as if we are witness to the entirety of human time. Whatever happens within this epic timeframe matters little in this zoomed-out scheme of things.

The sound and fury of humanity is reduced to a kind of dogged sameness. If you look carefully, though, you can discern individual dancers who wear fantastical costumes, beautifully wrought from lace, crochet, feathers and sticks.

We know these to be individuals but they are not marked according to any recognisable identity. Salamon refuses any divide between citizens, migrants, ethnicities and sexualities.

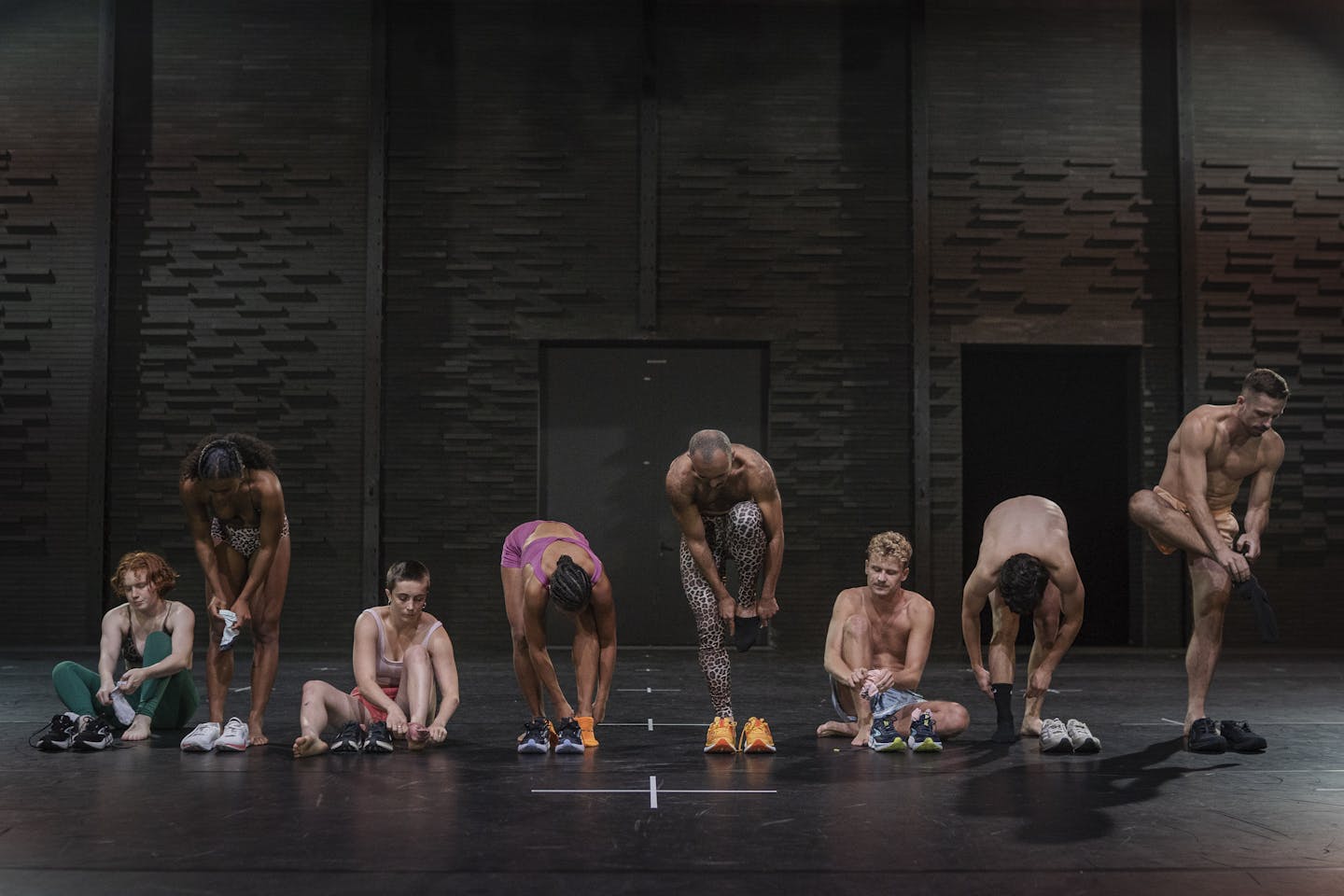

The abstracted humanity of the piece is ultimately undone, with the dancers undressing onstage before finishing up. Monument 0.10, The Living Monument offers a sweeping account of human destiny.

Through sustaining a sense of distance, it refuses judgement, preferring to offer us an experience of temporal infinitude.

Within the crowd

How different, then, is Gisèle Vienne’s Crowd, equally a form of social compact but with a deep investment in human interaction.

Crowd is a party piece, a techno-rave held in a former public transport maintenance building. A giant warehouse perfect for a real/unreal all-night gathering.

Two cars arrive with blinding headlights to deposit 18 young people in a great variety of outfits: street, leisurewear, jeans, lurex, casual, party.

As the group advances, a young man in a hoodie settles into position, a hostile man in black crosses the space, a young woman in a shiny top asserts her presence. Another arrives with blood issuing from her nose. Is she a victim of something, or just overdoing the drugs?

Over time, these individuals interact, nicely, not so nice, fumbling sexual advances, suffering rejection, creating and resolving conflict. The dancers look like real young people. They have been given a history, a backstory created by Dennis Cooper along with Vienne, which allows for a variety of not-that-great momentary relationships.

We’ve all been there. In fact, we are there, if not participating, then witnessing the drama alongside the rest of the partygoers. Although the audience is seated, there isn’t a sense of separation from the action: things happen close-up, with protagonists coming to the fore before melting into the crowd to reveal yet another vignette.

Crowd is a kind of modern-day War and Peace, a cast of individuals seeking love, status, power and connection. The incestuous hothouse of Russian aristocracy reinvented through the medium of youth culture. Crowd is a tale of fallible humanity told over the course of one long night.

Community

Several other works created a sense of community through conformity to a movement script which inevitably and ultimately admits of difference. Alejandro Ahmed’s Eunão Sousó Euemmim, I’m not just me in myself – State of Nature – Procedure 0.1 begins with the group repeating the same simple movement, over time giving way to a series of individual cameos.

Many of the works in the Biennale featured solos of one kind or another, as if we can only appreciate the individual when acting alone.

I want to suggest an alternative: that unison group activity is quite able to establish difference. The early section of Ahmed’s work allowed for contemplation of the very palpable differences between the performers, their energy, approach and technical prowess.

This sense of difference through conformity was amplified in Jan Marten’s The Dog Days Are Over, 2.0, in which eight dancers repeat the same movement over and over again.

Slight variations emerge, but the group stays together over myriad repetitions. They shout to synchronise – “count” – changing formation while maintaining the same moves.

At one point, for a few short beats, everyone is allowed to insert a signature movement. These are banal and unimportant in the greater scheme of things, quite different from the solo as an expression of individual virtuosity. The sheer length of repetition enables an appreciation of each dancer as a person conforming to a demanding, collective agenda.

So many ways to be who we are, together.

A place for discussion

This year the Biennale also featured a week-long forum of discussion and discourse.

Its opening ceremony was witness to First Nations artists from Australia, Brazil, Taiwan, the United States and Mozambique evoking the centrality of place and belonging within their artistic practice.

These Indigenous artists spoke of the responsibilities and protocols of making work, including the importance of heritage and ancestral relationships. This is not to downplay the creative possibilities of dance-making.

Inspired by corroboree, Wiradjuri artist Joel Bray spoke of his work Garabari as a form of new culture, suggesting Indigenous artforms can simultaneously follow protocol and respect heritage while creating cultural forms anew.

Australian guests of the forum, Marrugeku, are a case in point having made many works on Country, drawing upon a diversity of intercultural influences, while respecting and benefitting from cultural protocol and mentorship.

The evocation of group dynamics within the work speaks to the power of dance to enact a form of society beyond the idea of art as mere mimesis (reflection of that which already exists).

Dance is, in that sense, able to offer new perspectives on society and our place within it.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Philipa Margaret Rothfield, La Trobe University; University of Southern Denmark

Read more:

- The Australian Ballet’s flawless, breathtaking Prism is a significant coming of age for the company

- Two profound but different ballet legacies: vale Colin Peasley and Garth Welch

- Getting young and old people to dance together boosts health and reduces age discrimination – new research

Philipa Margaret Rothfield does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The Conversation

The Conversation

The Spectator

The Spectator Raw Story

Raw Story AlterNet

AlterNet New York Post

New York Post The Daily Beast

The Daily Beast Atlanta Black Star Entertainment

Atlanta Black Star Entertainment