Hobart’s Theatre Royal was packed to the rafters on a chilly October evening when the irrepressible nature warrior Bob Brown launched his latest book Defiance.

Given the state of the planet “we just have to be defiant”, Brown told the audience, as the image of activist Lisa Searle was projected onto the screen behind him.

Searle sat atop one of the world’s tallest flowering plants, a eucalyptus tree named Sentinel by its defenders, in Tasmania’s Styx Valley, perched there to prevent its destruction.

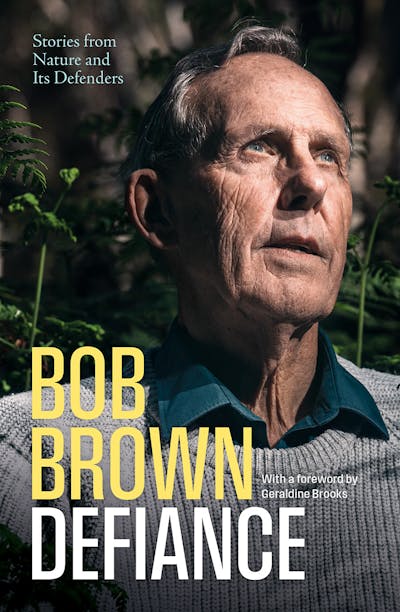

Review: Defiance: Stories from Nature and Its Defenders – Bob Brown (Black Inc.)

Writing is itself an act of defiance for Brown. Defiance is the latest and last in a long line of books. A collection of “musings about the human-induced plight of the planet”, it contains stories, calls to action, and odes to “our brilliant little planet”. It is written with thanks to “everyone who has ever lifted a finger to ward off its destruction”.

Some of these writings have appeared previously. Some are historical recollections. Many paint pictures of unique Australian environments and places, both protected and despoiled. But all of them decry “the escalating global overconsumption of Earth’s living resources”.

Communal action

Defiance calls for open resistance, taking the plunderers head on by “defying the laws that serve those who are exploiting the planet and its people”. But environmental activism is not just an act of defiance for Brown. It is also an antidote to depression.

He suffered from the “black dog” in the decade before he moved to Tasmania, where he fell in with local activists and, motivated by their ardour, soon found himself director of the nascent Tasmanian Wilderness Society. As history attests, Brown then plunged headlong into the ultimately successful campaign in the early 1980s to save southern Australia’s last great wild river, the Franklin.

Brown’s defiance began in the 1970s. As a young medical doctor visiting the United States, he protested in Chicago in support of students in Greece, who were opposing a military coup d’etat there. Two years later, he was camped out alone and fasting for a week atop kunanyi/Mount Wellington in Hobart in protest at the visit of the nuclear-armed aircraft carrier USS Enterprise.

It takes courage to be an environmentalist of Brown’s ilk. Over his activist years, which continue even today, he has been attacked physically and verbally, dragged from under bulldozers, arrested, jailed and shot at. But he has an uncanny way of shaking this off and seeing the upside.

When Brown found himself in Tasmania’s Risdon Prison for participating in the blockade against the flooding of the Franklin River, he played ping pong and volleyball and “enjoyed the features of jail which match the wilderness – no phones, no traffic, no slick advertising, and the early-to-bed, early-to-rise routine”.

Only defiant communal action, Brown argues, can keep the destruction of nature in check. If, as he writes, “materialism’s dream is of a virtual reality to replace the wild Earth”, we cannot stand by and do nothing. In Defiance, he evokes the great tradition of non-violent action, where “ordinary people take affairs into our own hands to overcome the power of corporate influence on governments”.

Brown intended Defiance to be a direct-action handbook, only to be overwhelmed by the stories of defiance and the good fights that needed telling. And there are many examples of communal action in his book.

Defiance is dedicated to Amrita Devi, the original tree-hugging activist, whose bravery has inspired forest defenders around the world. In 1730, Devi and her three daughters, along with 359 fellow Bishnoi people, were beheaded for obstructing the clearing of the Khejarli forest in Rajasthan, northern India.

Brown also celebrates “nature’s defenders” in Australia, including luminaries Melva and Olegas Truchanas, who tried to save Tasmania’s Lake Pedder, and Lionel Murphy, the High Court Justice who played a crucial role in saving the Franklin River.

He writes of Anmatyerr woman and globally renowned Indigenous artist Emily Kam Kngwarray, who believed the power of her work would protect her Country, and whose legacy includes the magnificent Earth’s Creation. Ordinary stories about local acts of defiance are equally acknowledged.

Dance, love, read a book

There is an element of being up against the impossible in such defiance. Today, the scales have tipped even further against activists, with laws in Australia curtailing civil disobedience.

Following its stories of collective action, Defiance turns to what activists are up against: the brutes in suits, “as rich in dollars as they are poor in spirit”.

Brown has no hesitation in denouncing their unrelenting pursuit of growth, because Earth’s living resources cannot sustain it. He delivers blistering broadsides against capitalism, corporations, plutocrats and “greenophobia”, which he calls “the fear or hatred of environmentalists”.

Brown has been staring down corporate power as an activist, green politician, state leader, Australian senator and environmental advocate for half a century. In Defiance, the conservative media, the egoists, the billionaires who rule the world, and the politicians who are too compromised or too feeble to resist corporate power are called out as complicit.

But Brown also makes it clear that having fun is not incongruent with saving the planet. Indeed, he warns that “angst at the imminence of Earth’s destruction isn’t helpful”. Anxiety shouldn’t trip you up on the path to action, he warns. There is always time on hand to turn things around. You can still “dance, love, be loved”, or read a book by the river.

This is not to treat environmental destruction lightly, but to sustain the human efforts to address it. After decades of activism, Brown remains full of optimism in Defiance.

Defiant people make things happen, author Geraldine Brooks observes in her foreword to the the book. Indeed, the arc of the moral universe only bends towards justice if brave people make it so.

There is no creeping conservatism about the octogenarian Brown; if anything, he is more infectiously defiant than ever. His book concludes with a series of odes to wild places that reveal his close, indeed transpersonal, connection with nature. He wants everyone to share how it feels to see a wedge-tailed eagle rise on thermals, or the sun break through the clouds and light up a patch of forest in a distant valley.

“We need natural beauty,” he writes, because “our minds and bodies are made for wildness”.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Kate Crowley, University of Tasmania

Read more:

- White elephant? Hardly – Snowy 2.0 will last 150 years and work with batteries to push out gas

- More whales are getting tangled in fishing gear and shark nets. Here’s what we can do

- View from The Hill: Liberals are now squabbling among themselves over Kevin Rudd

Kate Crowley does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The Conversation

The Conversation

CNN

CNN Arizona Daily Sun

Arizona Daily Sun Associated Press US News

Associated Press US News Reuters US Top

Reuters US Top AlterNet

AlterNet