This series of articles draws on a year of research conducted on board the Ocean Viking, the civilian search-and-rescue ship operated in the central Mediterranean by the NGO SOS Méditerranée. It explores the perspectives of exiled people based on testimonies from 110 survivors who were picked up while attempting the crossing from North Africa, as well as crew members’ experiences and the researcher’s creative collaborations on board the ship.

This is the second of a four-part series – read part one here and part three here, and explore an immersive French-language version of the series here.

Fragments of journeys

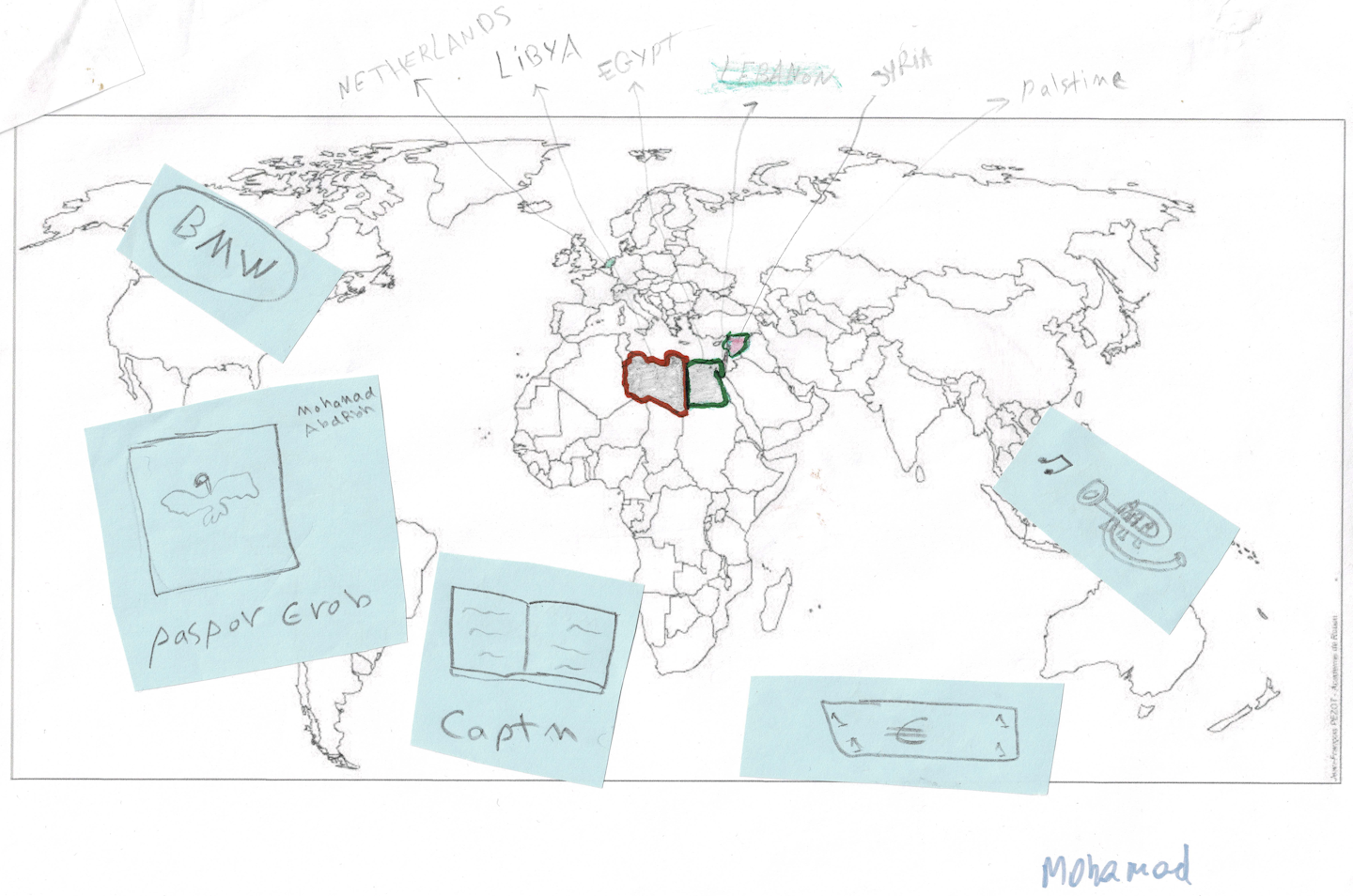

In all, 21 sketches were created in the workshops I conducted onboard the Ocean Viking. They tell fragments of journeys – routes that were sometimes smooth but often fraught, starting from Bangladesh, Pakistan, Syria, Palestine and Egypt.

Some journeys were very costly but quick and organised, such as those of some Bangladeshi individuals who had travelled from Dhaka to Zuwara via Dubai in just a few days. Others stretched and intertwined over several years, adapting to encounters, resources, dangers and the multiple wars and violence in those countries crossed.

Among 69 people who responded to the questionnaire, 37.6% had left their country of origin the same year. But 21.7% had been travelling for more than five years – and 11.5% for over ten years. The longest journeys began in countries as diverse as Nigeria, Sudan, Eritrea, Ethiopia and, in 60% of the cases studied, Syria. As one respondent explained:

I fled the Syrian army. I spent three years in prison and torture, saw terrible scenes. I was 18, I was not old enough to live or see such things.

2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015: the steady spread of departure dates for these journeys highlights the persistence of the conflicts that drive migration around the world. Motivations to continue these long journeys are often personal ambitions for a better life, such as being able to study or help family left behind – as was explained by a young Egyptian man: “I am the only son in my family. My parents are old and they are worried I won’t make it.”

The survey made it possible to outline the types of support received and the dangers encountered along the way. Alongside financial resources from personal savings or family loans, nearly 60% of respondents mentioned the importance of immaterial resources such as “advice from friends”, “psychological support from my husband”, or “information and emotional support from my niece”.

For some, the information received from loved ones seemed crucial at certain stages of the journey: as one respondent explained, it provided moral support to “survive in Libya”. Conversely, another participant confided it had been essential to hide the realities of their daily life in Libya from their family, in order “to hold on”.

Indeed, it was in this North African country that most difficulties were encountered: among the 136 situations of danger described, half were in Libya – compared with 35.3% at sea, 8.8% in the person’s country of origin, and 5.9% at other borders along their migration routes.

‘Inhumane acts’ against people in exile

The atrocities targeting people on the move in Libya are now well-documented. They appear in numerous sources including NGO reports and documentary films, as well as direct testimonies from those affected.

The findings of an independent UN Human Rights Council fact-finding mission, published in 2021, qualified these realities as crimes against humanity. The report described “reasonable grounds to believe that acts of murder, enslavement, torture, imprisonment, rape, persecution and other inhumane acts committed against migrants form part of a systematic and widespread attack directed at this population, in furtherance of a State policy. As such, these acts may amount to crimes against humanity.”

Through the study on board the OV, participants were able to define, in their own words, the nature of the dangers they had experienced there. Their quotes conveyed subjective, embodied experiences reshaped by emotions – yet they were numerous and convergent enough to reconstruct what has been happening in Libya. The mechanisms of the reported violence were systemic: punitive detention combined with torture, inhumane and degrading treatment, racial and sexual violence endured or witnessed. And these acts were often cumulative:

During my first period in Libya, I was imprisoned six times, tortured, beaten. I can’t even remember the exact details.

The acts of violence involved perpetrators who were, to a greater or lesser degree, institutionalised, including coast guards, prison guards, mafias, militias and employers. They occurred across the entire country (Benghazi, Misrata, Sabratha, Sirte, Tripoli, Zawiya and Zuwara were the most frequently cited cities), but also in the desert and in detention sites at unknown locations. Omnipresent was the prospect of violent and arbitrary detention, which generated a presumption of widespread racism against foreigners:

The racism I experienced as an Egyptian is just unimaginable: kidnapping, theft, imprisonment.

Black people felt particularly targeted by such attacks. Among those who testified, an Ethiopian man trapped for four years in Libya described his constant sense of terror, linked to the repeated racist arrests he had endured:

People get kidnapped in Libya. They catch us and put us in prison because we don’t have papers. Then we have to pay more than US$1,000 to be released. It happened to me four times: two weeks, then a month, then two months, and finally a year. All because of my skin colour – because I am black. It lasted so long that my mind is too stressed from fear.

Such racial discrimination was confirmed by the UN Human Rights Council report in 2021, which found “evidence that most of the migrants detained are sub-Saharan Africans, and that they are treated in a harsher manner than other nationalities, which suggests discriminatory treatment.”

However, the risks of kidnapping and ransom would appear to spare no one on Libyan soil. Koné described them as a generalised and systemic practice:

There’s a business that many Libyans run. They put you in a taxi which sells you to those who put you in prison. Then they demand a ransom from your family to get you out. If the ransom isn’t paid, you’re made to work for free. In the end, in Libya you’re like merchandise: they let you enter the country only to make you work.

Several study participants had been caught in these networks, and their analyses afterwards converged on one point: the Libyan experience amounts to a vast system of exploitation through forced labour.

The facts reported match the International Labour Organization’s definitions of “human trafficking” and “modern slavery”, and were again confirmed by the UN report, which noted: “The only practicable means of escape is by paying large sums of money to the guards or engaging in forced labour or sexual favours inside or outside the detention centre for the benefit of private individuals.”

Ultimately, what Koné remembered most painfully was the feeling of shame:

I pity myself, my story, but I pity the people who went to prison even more. If your family can’t pay the ransom, they must take on debts, so it’s a problem you put on your family. Some people went crazy because of it.

Mapping as testimony

While the accounts of time spent in Libya were always bitter and often horrifying, sometimes beyond words, the study revealed a strong desire to bear witness to what happens there – not only for the general public, but for those who might attempt the same journey:

I want to say that in Libya, there are many women like me who are in a very difficult situation.

I don’t have much to say, except that so many people are suffering even more than I did in Libya.

I don’t advise anyone to come by this route.

To accompany these stories, our mapping workshops aboard the OV served as an invitation – an opportunity to share experiences without having to put traumatic events into words.

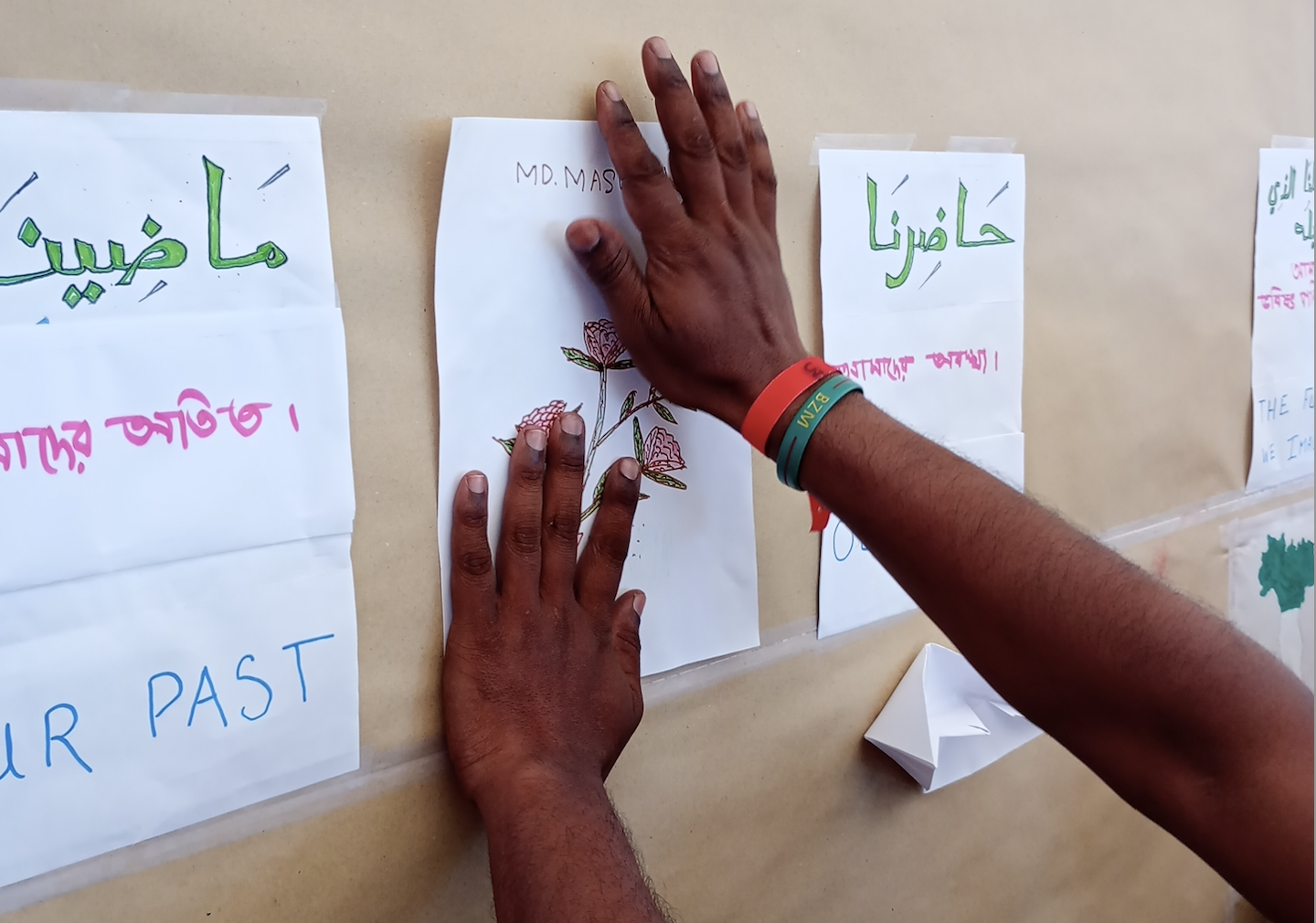

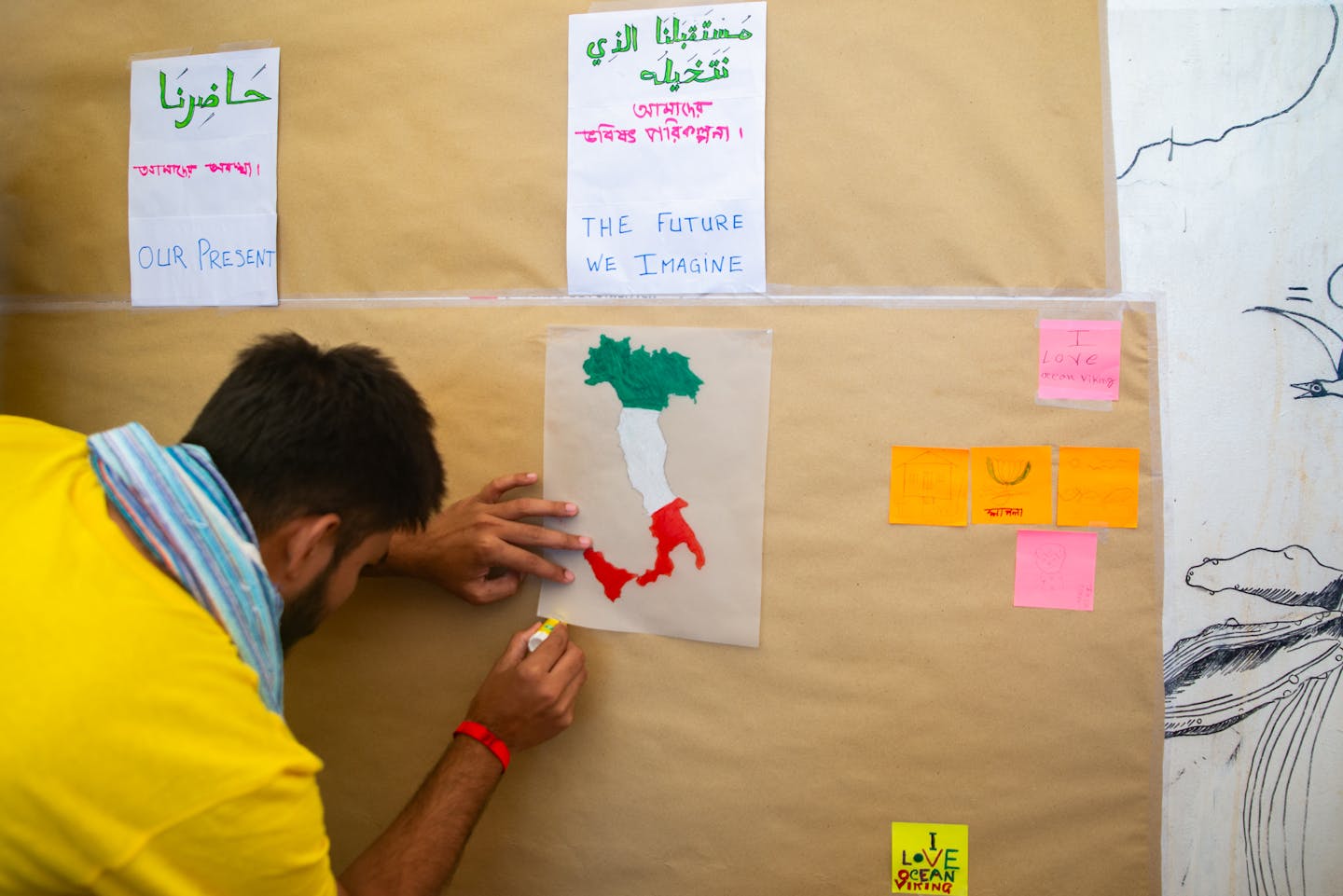

At first, the collective mappings organised on the OV’s deck allowed participants to bring out the main themes they wanted to address, according to three sequences: “our past”, “our present”, and “the future we imagine”. My role was to create an appropriate framework for expression, guide participants toward accessible graphic techniques, and enable the sharing of creations through their gradual display on the deck.

Workshops were then offered to small groups or individuals inside containers – spaces that were more conducive to the confidentiality of intimate stories.

One of the tasks suggested by participants was to represent the zones of danger felt throughout the migration journey — where Libya inevitably stood out. From these personal pathways, a second exercise was introduced: describing the experience of danger at the Libyan scale, building on the places already mentioned.

Participants were encouraged to enrich their sketched maps with personal illustrations and narrative legends in their native languages, which were later translated into English.

Ahmed’s experience of Libya

On his map, Ahmed, a Syrian-born participant, depicted “insecurity” in Tripoli, “bad treatment and extortion of money” in Benghazi, and “violation of rights” in Zuwara.

His illustration shows a scene of ordinary, widespread crime: “the Libyan” shooting at “foreigners” evokes the collective violence that Ahmed described as occurring all across Libya. This emotional and participatory method served as a language for sharing stories that were difficult to verbalise, and for mediating them.

Beyond what these drawings facilitated for those sharing their stories, they allowed myself and others observing these violent images to contextualise them within a complex web of factors across time and geographical space.

Now read part three in this four-part series, or explore an immersive French-language version here.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Morgane Dujmovic, Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS)

Read more:

- ‘We were treated like animals’: the full story of Britain’s deadliest small boat disaster

- Slave auctions in Libya are the latest evidence of a reality for migrants the EU prefers to ignore

- Migrants calling us in distress from the Mediterranean returned to Libya by deadly ‘refoulement’ industry

Morgane Dujmovic does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The Conversation

The Conversation

Reuters US Domestic

Reuters US Domestic KRWG Public Media

KRWG Public Media Reuters US Politics

Reuters US Politics El Paso Times

El Paso Times NBC News

NBC News AlterNet

AlterNet The Bay City Times

The Bay City Times Reuters US Top

Reuters US Top