When Russian president Vladimir Putin visited Beijing in September 2025, he told Chinese leader Xi Jinping that repeated organ transplants might make a person “get younger” and even live to 150. The remark was widely dismissed as science fiction.

Yet it coincided with genuine scientific progress. Just days earlier, researchers had identified a molecular “switch” that could reduce one of the most common complications in liver transplants, helping donated organs survive longer.

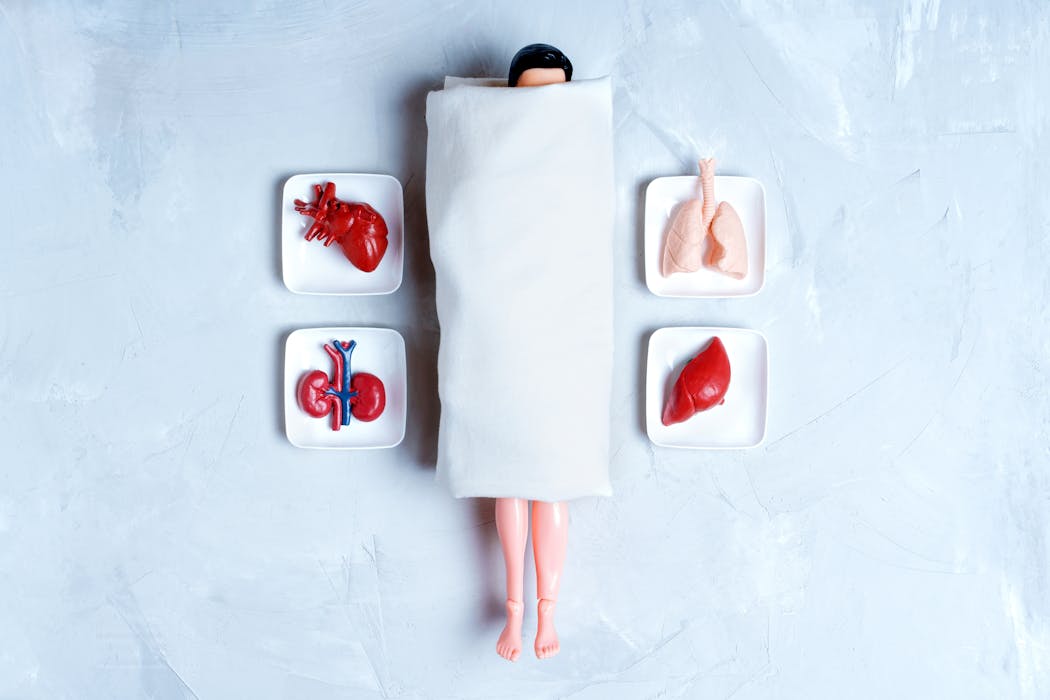

That breakthrough highlights both the promise and limits of transplant medicine. While science continues to improve the odds of saving lives by replacing failing organs, the idea of swapping body parts to slow ageing remains closer to gothic horror than medical reality.

The dream of replacing body parts to restore youth is not new. In the early 20th century, “monkey gland” transplants – grafts of monkey testicles – briefly became fashionable among wealthy men chasing renewed virility.

A century later, tech entrepreneur and self-described biohacker Bryan Johnson has revived that quest for eternal youth through blood-based treatments such as blood plasma transfusion. This involves injecting blood plasma concentrated with platelets to promote healing and regeneration, or transfusing “young blood” – plasma taken from healthy younger donors – into older recipients in the hope of slowing ageing.

The idea stems from parabiosis experiments in mice, where the circulatory systems of young and old animals were surgically joined. In these studies, older mice showed short-term improvements in muscle tone, tissue repair and cognitive function. But these effects have not translated to humans.

Clinical trials using plasma from young donors have produced no meaningful anti-ageing results, and the practice has drawn criticism for its ethical implications. In 2019, the US Food and Drug Administration warned against commercial “young blood” transfusions, calling them “unproven and potentially harmful”. Still, the fantasy persists: that youth might be extracted, bottled and sold to those rich enough to afford it.

Transplants save lives but they cannot reset them

Today, legitimate organ and tissue transplants are used to save lives when a vital organ fails completely. Donor organs are carefully matched to recipients based on tissue compatibility and screened for diseases, tumours and viruses to give the best chance of long-term survival. Yet this life-saving therapy still carries major risks.

As Katie Mitchell, the UK’s longest-living heart-and-lung transplant patient, has shown, success requires lifelong care and resilience. The body’s immune system naturally views a transplanted organ as a foreign invader. Without powerful immunosuppressant drugs, it will destroy the new organ within weeks.

Suppressing this immune response allows the host body to tolerate the transplant, but it also leaves the recipient more vulnerable to infections and some cancers. Over time, the immune system’s constant low-level attack on the transplanted tissue causes inflammation and scarring, eventually leading to chronic rejection. Even the most advanced drugs cannot always prevent this process, and lifelong treatment takes a heavy toll on the patient’s overall health.

These complications become more severe with age. Older patients have weaker immune systems, slower tissue repair and greater baseline inflammation, all of which make recovery from major surgery harder and rejection more likely. Studies show that survival rates after repeated or multi-organ transplants decline sharply in older adults, as ageing tissues struggle to heal and adapt.

One thing is clear. Transplants can extend life, but they cannot reset it. The biological cost of surgery and the strain of lifelong immunosuppression mean there is no simple upgrade for the human body.

Scarcity, ethics and the dark market for organs

Organs suitable for transplanting are scarce. The waiting list for donor organs is long in almost every country, with demand far exceeding supply. This imbalance fuels a dangerous black market, with a global trade in trafficked organs taken from vulnerable populations in poorer regions and sold illegally to wealthier buyers.

Read more: Prisoners donating organs to get time off raises thorny ethical questions

The scarcity of donor organs does not just cost lives – it shapes the ethics of innovation itself. To overcome shortages, scientists have explored xenotransplantation, the transplantation of animal organs into humans – most often from pigs or baboons because of their anatomical similarities. While promising in theory, xenotransplants face severe immune rejection, with most organs failing within days or weeks.

Cloned or lab-grown organs offer another path forward. Researchers can now cultivate miniature organoids – simplified versions of human organs – but creating full-sized, fully functional, transplant-ready organs remains beyond current technology.

This scarcity raises difficult ethical questions. If a healthy, tissue-matched organ became available, who should receive it: a child or an elderly patient? Using a rare donor organ for someone whose existing organ still functions, albeit less efficiently, would be hard to justify.

These dilemmas matter because they strike at the heart of medical ethics. The guiding principle in transplant medicine is to allocate organs to the recipient who would gain the greatest benefit – the person most likely to live longest and with the best quality of life. Using scarce donor organs for elective “anti-ageing” surgery would not only violate this principle, but risk undermining public trust in the entire transplant system.

Finally, not all organs can be replaced. The brain, which defines consciousness and identity, remains uniquely fragile and irreplaceable. It is prone to age-related decline including memory loss, inflammation and degenerative diseases.

Unlike the heart or kidneys, brains cannot simply be swapped out or rejuvenated. Even if scientists one day learn to replace every other organ in the body, the brain’s complexity and its role in defining who we are ensure that true immortality will remain out of reach.

The dream of eternal youth through transplants is not medicine’s next frontier. It is a mirror reflecting our refusal to accept that ageing is not a mechanical fault to be fixed, but a vital part of what it means to be human.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Dan Stratton, The Open University

Read more:

- What medical history can teach us about reports of personality changes after organ transplants

- First UK birth after womb transplant is a medical breakthrough – but raises important ethical questions

- Lab-grown ‘ghost hearts’ work to solve organ transplant shortage by combining a cleaned-out pig heart with a patient’s own stem cells

Dan Stratton does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The Conversation

The Conversation

Local News in Florida

Local News in Florida People Top Story

People Top Story Southfield Sun

Southfield Sun Raw Story

Raw Story Sun Sentinel

Sun Sentinel Sarasota Herald-Tribune

Sarasota Herald-Tribune NBC News

NBC News FOX 13 News

FOX 13 News IndyStarSports

IndyStarSports