In the 1950s and 1960s, Elizabeth Harrower wrote some of the most intense and highly praised “psychological fiction” of the 20th century. Mysteriously, she stopped writing after shelving a manuscript for her last novel, In Certain Circles, in 1971. Her comeback story in the final decade of her life captured the public imagination and set two new biographies in motion.

Helen Trinca and Susan Wyndham both interviewed Harrower during her literary “renaissance”, before her death in 2020 at the age of 92. Their respective encounters with the elderly Harrower prompted them to write different versions of her life story.

Review: Elizabeth Harrower: The Woman in the Watch Tower – Susan Wyndham (New South), Looking for Elizabeth: The Life of Elizabeth Harrower – Helen Trinca (Black Inc)

Wyndham, a former literary editor of The Sydney Morning Herald and New York correspondent for The Australian, interviewed both Harrower and her friend, the late writer Shirley Hazzard. Along with Brigitta Olubus, she edited 400,000 words of their decades-long correspondence into a book.

Helen Trinca was a co-winner of the Prime Minister’s Prize for nonfiction in 2014 for a biography of Madeleine St John. She has co-written two other works of nonfiction and also worked for The Australian over many years, as a European correspondent and managing editor.

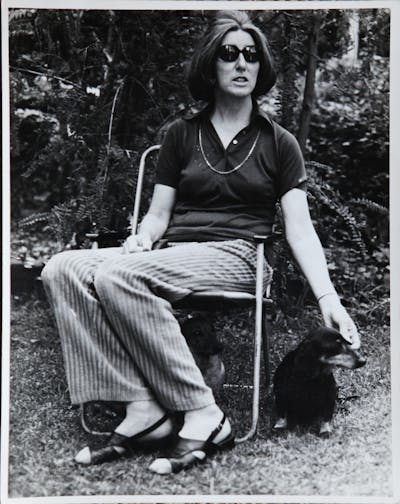

Trinca and Wyndham’s concurrent biographies pivot around the question of why Harrower stopped writing. Inevitably they must account for a long dry period between significant literary events but Harrower’s social life provides colourful material. Trinca’s biography contains some well chosen black and white photos, which complement the life stages she describes.

Early years

Born in 1928, Harrower’s childhood was an emotionally turbulent one – a key moment, when she lay down in the road hoping to be run over, indicates her level of desperation.

Her stepfather Richard Kempley was a monstrous figure, providing inspiration for the tyrannical Felix in her 1966 novel The Watch Tower. “Anger, discipline, rebellion, violence and self pity were built into Richard Kempley by nature and example,” Wyndham writes. He inflicted his sadistic personality on those in his orbit, especially Elizabeth and her mother Margaret.

Critic and writer Ramona Koval has drawn attention to Wyndham’s close identification with Harrower as a childless writer, the only child of divorced parents.

“From her earliest years,” Wyndham writes, “Elizabeth had a strong sense of the value of her mind and her work. People might let her down but words would always save her.”

Harrower’s prolific letter writing began in childhood when she wrote frequent letters of complaint to her divorced parents. These letters are a vital source of information for biographers, given her reticence to talk about her personal life.

By all accounts, she was particularly guarded about her early years, saving up the details for fiction. Harrower’s friend Sally McInerney told Trinca,

there was always a feeling that although her life was like a very welcoming house with many rooms, there were some rooms which visitors should not try to enter.

A blackbird

Harrower lived in the United Kingdom from 1951-1959. Her four novels came out in a flurry from 1957 onwards. Down in the City was initially submitted under the authorial name of Antonia Field, possibly because it was partly inspired by Harrower’s personal history. In 1956 when Harrower signed a contract with Cassell, the name Antonia Field was replaced by her own. Reviewers, writes Trinca, expressed surprise that Harrower could evoke the streets of Sydney from a London council flat.

The Long Prospect, her second novel, which also drew on her Newcastle childhood, was compared to D.H. Lawrence and Katherine Mansfield but there were few local points of comparison. Notably, Harrower was not engaged with the Australian literary scene at all until she moved back to Sydney with her cousin Margaret Dick in 1959.

Harrower’s novels can be an acquired taste for many readers given their concern with difficult people doing damage to others. She clearly recognised the richness in repetition:

A blackbird always sings the same song. I just do have preoccupations, but you can come at them from so many different angles.

Wyndham connects the life with the work, showing ample evidence Harrower’s stepfather and others caused immense pain to the sensitive child and young woman. Later, Harrower reflected on the the way powerful personalities may not realise – or care – about the echoic effects of their words.

Uncontrolled, violent, negative emotions are intimidating. Many people don’t mind what they say, as if words had no meaning and no effect and their hearers no memories and no feelings …

The character Harrower is best known for is Felix, the gaslighting abuser of sisters Clare and Laura in The Watch Tower. They are trapped in a domestic prison (or watch tower) from which the younger Clare must free herself, since Laura has been brainwashed into total subjugation.

Poet Judith Wright praised Harrower for her “analysis of the forces that drive the awful Felix” arguing she shows what “really happens to women in such situations”.

The Watch Tower was acclaimed by reviewers from The Sydney Morning Herald and the ABC among others, however Harrower felt her publisher Macmillan did not promote or distribute the novel effectively enough, limiting the potential readership.

Harrower then went on to write In Certain Circles, which is set amid the “lush gardens and grand stone houses” on the north side of Sydney harbour, featuring two pairs of siblings who move in and out of each other’s lives.

She sent it to Macmillan, the company she worked for in Sydney, then to an agent for advice. Both offered very lukewarm appraisals, which reinforced her ambivalence: “I have never written a novel I liked less,” she wrote to her London agent. The correspondence suggests these publishing figures merely underlined her poor opinion of the novel, leading to its retraction.

As Trinca puts it, she “turned her back on her typewriter and her talent in the 1970s.” In a 2015 interview, Harrower described her decision to stop writing as “a total severing, as if someone had gone off to war and never returned.”

Wyndham determines that Harrower adapted a section of In Certain Circles into “A Few Days in the Country”, a self contained story about a character’s suicide, which was published in Overland in 1977. (The suicide of Cynthia Nolan, artist Sidney’s accomplished wife, may have been at the forefront of her mind when she submitted this story, even though it was derived from an earlier work.)

Inevitably, the biographies speculate about the reasons for her writer’s block but perhaps the miracle is that she wrote anything at all given the barren atmosphere of her childhood.

Trinca surmises that the unravelling of Harrower’s friendship with author Kylie Tennant was related to “the beginning of the end” of Harrower’s career. Yet it was more likely to have been caused by a combination of factors: poor responses to In Certain Circles, her failure to win the Miles Franklin Award with The Watch Tower in 1967 and her beloved mother’s premature death in 1970.

Her bifurcated career illuminates the question of whether you can still be considered a writer when your work is no longer being published. As Wyndham observes, Harrower clearly valued the “non-writing part of writing: the time spent thinking about things, people, the how, why […]”.

A Literature Board grant Harrower received in 1976 prompted her to write some shorter pieces and an unfinished novel set in the “Department of Information”, a television or film-making organisation resembling her previous workplaces Macmillan and the ABC.

Wyndham’s investigation of notes relating to this “lost novel” demonstrates her forensic attention to Harrower’s texts, both extant and “stillborn”.

A renaissance

Harrower had been optimistic about Angus & Robertson’s new edition of The Watch Tower in their “classics” series in 1977 but it featured an off-putting blurb suggesting Felix might be wicked because he “suffered a deprived childhood” or was a “homosexual”. She wrote to Hazzard: “A&R did me no favour with that tatty Australian Classics edition.”

From the mid 1970s Harrower slipped out of view and an image of neglect took hold. Anne Summers’ wrote in her 1975 feminist history Damned Whores and God’s Police,

Elizabeth Harrower must possess a very special strength and conviction to be able to continue to write her splendid books about women for a world that mostly fails even to acknowledge their [the books] existence.

While Harrower welcomed scholarly interest in her work, she disliked the label “feminist”. Notably, it was feminist critics who brought her back into the public eye from the 1980s onwards, along with Melbourne’s Text Publishing.

At the age of 83, Harrower received a letter from Text asking to republish The Watch Tower. As Trinca notes, it was the beginning of a strong friendship between Harrower and Text principals Michael Heywood and Penny Hueston and a “joyous publishing experience”, unlike some of her previous transactions.

Harrower has been characterised as reclusive, a label frequently applied to disappearing writers, but Wyndham explodes this idea, saying “reclusive was an odd description for this sociable woman”.

Both biographies grapple with the reasons for Harrower’s reluctance to “settle down”. Trinca infers she was a lesbian in love with her female friends. Since she lived with her cousin Margaret Dick for decades, they were often invited to events together, due to what Wyndham characterises as “familial symbiosis”.

Wyndham reflects that Harrower consciously avoided marriage and may have been “temperamentally unsuited” to motherhood. Evidently she had a few close male friends and a number of lovers who failed to measure up.

Because she didn’t have her own nuclear family, people repeatedly called her for help and support, which could be draining and distracting. One such person was Shirley Hazzard, who allowed Harrower to look after her mentally ill mother Kit in Sydney, while Hazzard and her husband lived in New York and Capri.

Harrower attracted a new readership in her final years, thanks to the republication of her oeuvre and release of her archived manuscript In Certain Circles by Text, four decades after she had put it aside.

Bittersweet

Trinca opens her biography with the 2015 Prime Ministers Literary Awards ceremony at Carriageworks in Sydney. Harrower, then 87, was in the running with In Certain Circles. She had missed out on the Miles Franklin with The Watch Tower in 1966, and on this occasion she was outshone by Joan London’s The Golden Age.

Trinca likes to describe Harrower’s physical appearance as a supportive friend might. When she was being interviewed by Heywood at the Mosman library in 2015, “she wore a terrific black pants suit and simple necklace. Her face was lined but she looked a decade younger than her 87 years”.

She reports a number of comments from other people present, who were amazed at Harrower’s ability to cope with all the attention at an advanced age. Trinca herself was present at the dinner after this event and attests to Harrower’s difficulty in hearing over the noise.

Throughout her Sydney years, Harrower was deeply involved with the literary scene. The fact that she was surrounded by other writers may have made her publishing drought more conspicuous. She was a close friend of Patrick White, Christina Stead, Cynthia Nolan and Kylie Tennant, amongst others.

Trinca suggests White inhibited her career and dominated her social world. However Wyndham shows Harrower was not a follower or “Lady Disciple” (White’s partner Manoly Lascaris’ term). It was a genuine, long-term friendship both valued.

Wyndham depicts the literary renaissance as bittersweet for Harrower. It had “come too late”. She was tired and mourning her cousin Margaret, who was blind and in a nursing home, when the new Text editions of her novels started being re-released in 2012. Wyndham notes that none of her old friends who had “pushed and appreciated” her writing could share her pleasure.

Harrower and Hazzard’s relationship had been heightened and adversely affected by Harrower’s extensive care for her mother Kit. Wyndham suggests Harrower’s care was partly driven by her own mother’s death and the guilt that she couldn’t do more to save her from her controlling husband.

Critic Susan Lever has observed that Harrower seems to have resented being treated as a kind of honorary “poor relation” by Hazzard who led a cosmopolitan existence in New York and ultimately failed to return for Kit’s funeral. Wyndham writes: “Elizabeth had been congratulating Shirley for decades, and when her own celebration came, Shirley didn’t know.” (Hazzard, who died in 2016, was suffering from dementia in the last few years of her life.)

As Wyndham notes, personality differences marked their careers and friendship – Hazzard encouraged compliments while Elizabeth often found it hard to hear them.

Complexity

Little is revealed in these biographies about Harrower’s relationships with men, but there is ample evidence of intense friendship dramas. Wyndham suggests that Tennant and Cynthia Nolan were “in a contest for Harrower’s soul” in the early 1970s.

She went above and beyond what is normally expected of a friend. Her support of people with challenging mental health, also including Tennant’s son Bim, shows she had a compassionate nature.

This care for others extended to firm support for the Whitlam government’s ambitious program of change. As a member of the Australian Labor Party, Harrower was horrified by the dismissal of Gough Whitlam, which she saw as the death of democracy. She had come to know Whitlam personally though Patrick White and enjoyed a friendship with the former’s sister Freda and wife Margaret.

She wrote to Hazzard about her trip to Parliament House in November 1975 after the dismissal:

People surged there from everywhere. It was so AWFUL. Everyone was outraged. Our votes meant nothing. Moderate reform is not allowed to take place here.

As she entered her 60s, there was a “season of loss” as her best friends passed on, leaving a social void. In the late 1980s and early 1990s she was popular with biographers wanting to talk about her writer friends White, Judah Waten and Christina Stead yet she worried about how much to expose. Wyndham drily comments that her friends demanded attention even when they were dead.

If she had written her own memoirs, perhaps she might have written something like British playwright John Osborne’s two-volume work, which tells of a lower-middle-class boy who hated his mother and loved his father, though the order was reversed for Harrower herself. Trinca infers that she was “emotionally dependent” on her mother and makes a link with her “crushes” on older women.

Trinca does not dwell on the end of Harrower’s life, noting

she did not have a good death in the orthodox sense of the term; she had dementia and was confused as she lay in her bed at the nursing home.

Wyndham offers more detail. Her friend Ferdi Nolte’s daughter Linda sat with her as she faded away.

Linda remembered:

When she had the shot of morphine she looked at me, she held my hand and said ‘That’s wonderful, thank you’. And then shortly after that she left.

Harrower disliked funerals therefore Linda respected her wishes. Her body was cremated and the ashes scattered in a stream that ran off a cliff edge in the Grose Valley, off Blackheath, where she had spent time with Tennant and her family. People who knew Harrower were outraged by the lack of ceremony, but obituaries referred to her as a “rock star writer”, a “genius” and “acclaimed novelist”.

Overall, Trinca is more preoccupied with tracing patterns in Harrower’s life, focusing on tumultuous moments, especially friendship crises. Wyndham offers more subtle readings of the texts and deftly steers away from lazy assumptions or overstatement, allowing Harrower’s complex character to emerge.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Brigid Magner, RMIT University

Read more:

- ‘We just have to be defiant’: irrepressible environmentalist Bob Brown reflects on a life of activism

- Mandy Sayer’s memoirs challenge the accepted boundaries of a father-daughter relationship

- Harper Lee’s unpublished stories are not ‘thrilling’ – but offer insight into a literary legend

Brigid Magner does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The Conversation

The Conversation

IMDb TV

IMDb TV The Daily Beast

The Daily Beast Truthout

Truthout New York Post

New York Post