Across Jamaica, streets are littered with torn-off roofs, splintered wood and other debris left in the wake of Hurricane Melissa. Downed power lines have left communities in the dark, and many flooded and wind-damaged homes are unlivable.

Recovering from the devastation of one of the Atlantic’s most powerful storms, which struck on Oct. 28, 2025, will take months and likely years in some areas. That work is made much harder by the isolation of being an island.

As a researcher who has extensively studied disaster recovery in Puerto Rico after Hurricane María in 2017, I know that the decisions Jamaica makes in the days and weeks following the disaster will shape its recovery for years to come. Puerto Rico’s mistakes hold some important lessons.

Why island recovery is different

Islands face obstacles that most mainland communities don’t experience. Geographic isolation compounds every problem in ways that make both the emergency response and the long-term recovery fundamentally harder.

Communities can easily be cut off by damaged roads, particularly in rugged areas like Jamaica’s Blue Mountains. Every damaged port facility, every closed airport, every blocked road multiplies isolation in both the short and long term.

As Puerto Rico saw after Hurricane Maria, in the early days after a disaster, basic emergency supplies like tarps, batteries, fresh food and water and generators can become scarce.

Weeks and months later, reconstruction materials can still take a long time to arrive, extending the recovery time far beyond what most mainland communities would experience. This isn’t just a price-gouging ploy; it’s the reality of island supply chains and shipping infrastructure under stress.

Research on Hurricane Maria’s impact on Puerto Rico has shown how an island’s isolation, limited port capacity and dependence on imports create unique vulnerabilities that slow disaster recovery.

Local organizations: From response to recovery

One of the most important lessons I saw in Puerto Rico is that local nonprofits and community organizations are essential first responders in the emergency phase and then transition into recovery leaders.

These organizations know their communities intimately: who is elderly and homebound, which neighborhoods will have the greatest need, and how to navigate local conditions.

Right now, Jamaican churches, community groups and local organizations are in emergency response mode — checking on residents, distributing water and providing shelter. For example, the Jamaica Council of Churches, which has extensive disaster response experience, has started to coordinate relief efforts though its community networks.

Over the long term, my research shows that local organizations are crucial for helping families recover. They help to navigate insurance claims, organize rebuilding efforts, provide mental health support, and advocate for community needs in recovery planning, among many roles.

However, many disaster recovery funding sources favor larger, international nonprofits over local groups, even for distribution once supplies have arrived. In Puerto Rico after Hurricane María, only 10% of the nearly US$5 billion in federal contracts went to Puerto Rico-based groups, while 90% flowed to mainland contractors.

Jamaica will face similar dynamics as international funding arrives from sources such as the World Bank and Inter-American Development Bank. Ensuring the recovery funding goes through established Jamaican organizations can help the recovery.

The diaspora: Urgent help, long-term support

When institutional systems such as the Federal Emergency Management Agency and the government of Puerto Rico could not offer aid fast enough after Hurricane Maria, diaspora communities became crucial lifelines. Puerto Ricans in Chicago, New York and Florida organized relief efforts, raised funds and shipped supplies within days.

Months later, Puerto Ricans living on the U.S. mainland continued providing financial support. They hosted displaced family members and advocated for federal aid. As my co-author Maura I. Toro-Morn and I document in our book “Puerto Ricans in Illinois,” diaspora communities that mobilized statewide in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria demonstrated how Puerto Ricans supported the island during crisis.

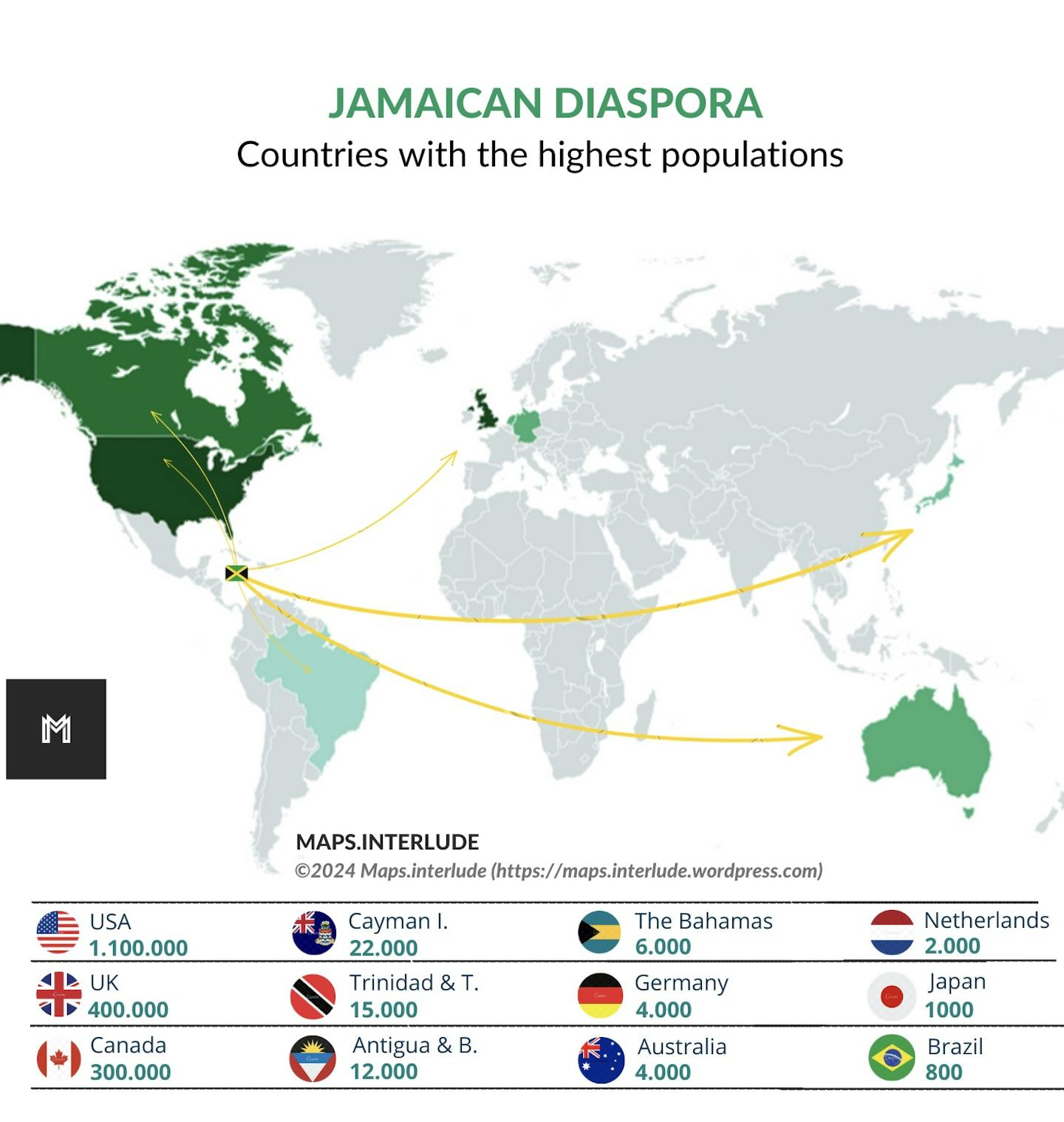

The Jamaican diaspora in London, Toronto, New York and Miami represents a massive potential resource for both immediate relief and long-term recovery.

In the hours after Melissa made landfall, these communities were already trying to reach family members and organize help. In Florida, Jamaican American student associations at several universities set up a GoFundMe page for relief efforts in Jamaica. In Connecticut, Caribbean social groups were gathering their communities to send support.

Jamaica’s government has multiple diaspora engagement platforms, such as JA Diaspora Engage, the Global Jamaica Diaspora Council and JAMPRO. But these primarily focus on economic development and investment rather than disaster response coordination. In contrast, Haiti established the Haitian Diaspora Emergency Response Unit in 2010 specifically for disaster coordination. After the 2021 earthquake, it coordinated relief efforts across more than 200 organizations, raising $1.5 million within weeks.

Jamaica could adapt its existing diaspora infrastructure to include an emergency response component. It could provide regular updates on community needs during disasters, verify trusted local partners for aid distribution, and facilitate logistics for shipping supplies over the years of recovery.

The out-migration risk: When emergencies becomes permanent

Perhaps the most devastating long-term impact of Hurricane María was massive population loss — a recovery failure that began with emergency response decisions.

Of Puerto Ricans who applied for federal assistance, approximately 50% had new addresses on the U.S. mainland. Their displacement that began as a temporary evacuation became permanent when Puerto Rico couldn’t restore viable living conditions quickly enough.

Without housing, employment or basic services for months, families had little choice but to leave. About a quarter of Puerto Rico’s schools were closed by the storm damage. I saw similar patterns in Maui, Hawaii, as it recovered from devastating wildfires in 2023. Limited lodging and high costs made it impossible for many displaced residents to stay.

Researchers estimated that of the nearly 400,000 people who left Puerto Rico in 2017 and 2018 after María, maybe 50,000 had returned by 2019.

Jamaica faces similar risks. The out-migration crisis doesn’t happen all at once – it’s a slow bleed that accelerates as emergency response transitions into prolonged recovery.

The time to prevent that pressure to leave is now. The government can help by communicating realistic timelines for service restoration and prioritizing school reopening. Every week increases the risk that temporary displacement becomes permanent emigration.

Building back better: Recovery, not just response

Disasters create opportunities to build back better, but that requires thinking about the future rather than simply recreating what existed before.

Jamaica can prioritize speed in emergency response by rebuilding the old system, or it can invest in a recovery that also builds resilience for the future. Climate change is fueling more intense and destructive hurricanes, leaving Caribbean islands at growing risk of damage.

Hurricane Maria revealed serious infrastructure vulnerabilities as the aging power grid collapsed under Category 4 winds. Puerto Rico could have rebuilt with more modern, resilient infrastructure. However, RAND Corporation research found that reconstruction largely restored the old, vulnerable centralized power system, rather than transforming it with distributed renewable energy, hardened transmission lines and microgrids that could withstand future storms.

Water systems, roads, schools and hospitals could also be rebuilt to better withstand storms and with redundancy – such as backup power sources and distributed water systems – to help the island recover faster in future hurricanes.

These improvements are expensive, and Jamaica will need international donors to help fund the recovery, not just the immediate emergency response.

The decisions made today will echo for years. Jamaica’s recovery doesn’t have to repeat Puerto Rico’s mistakes.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Ivis García, Texas A&M University

Read more:

- Hurricane Melissa turned sharply to devastate Jamaica − how forecasters knew where it was headed

- Colonialism’s legacy has left Caribbean nations much more vulnerable to hurricanes

- Military mission in Puerto Rico after hurricane was better than critics say but suffered flaws

Ivis García receives funding from National Science Foundation, U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Ford Foundation, National Academy of Sciences, Fundación Comunitaria de Puerto Rico, UNIDOS, Texas Appleseed, Natural Hazard Center, Chicago Community Trust, American Planning Association, and Salt Lake City Corporation.

The Conversation

The Conversation

ABC30 Fresno World

ABC30 Fresno World The Weather Channel

The Weather Channel The Daily Sentinel

The Daily Sentinel KNAU

KNAU Reuters US Top

Reuters US Top CNN Climate

CNN Climate CNN

CNN New York Post

New York Post CBS News

CBS News The Daily Beast

The Daily Beast Bozeman Daily Chronicle Sports

Bozeman Daily Chronicle Sports