Content warning: this article includes graphic details about sexual assault some readers may find distressing.

Prince Andrew will be stripped of his royal titles, including prince, and will move out of his home, Royal Lodge, to a private residence. Buckingham Palace issued a statement today that King Charles has initiated a formal process to remove the “style, titles and honours of Prince Andrew”, who “will now be known as Andrew Mountbatten Windsor”.

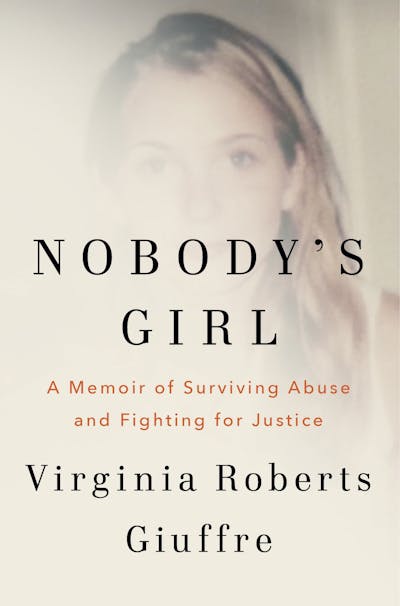

The decision comes in the wake of Virginia Giuffre’s posthumous memoir Nobody’s Girl, published this fortnight. The memoir includes an inside account of the two years Giuffre spent as a “sex slave” working for Jeffrey Epstein and co-conspirator Ghislaine Maxwell. Giuffre died by suicide in April this year, aged 41, on her farm in Western Australia.

Three weeks before she died, she emailed her co-author, journalist Amy Wallace, and longtime publicist Dini von Mueffling: “In the event of my passing, I would like to ensure that Nobody’s Girl is still released.”

“Today,” Giuffre’s family said, “she declares a victory. She has brought down a British prince with her truth and extraordinary courage”.

British historian and author Andrew Lownie (author of a book about Andrew and his ex-wife Sarah Ferguson, called Entitled), told Sky News earlier this month, “the only way the story will go away is if [Andrew] leaves Royal Lodge, goes into exile abroad with his ex-wife, and is basically stripped of all his honours, including Prince Andrew”. Sarah Ferguson will also move out of Royal Lodge.

As a trauma memoir, Nobody’s Girl forces us to bear witness to an uncomfortable truth: Giuffre’s abuse was hidden in plain sight.

“Don’t be fooled by those in Epstein’s circle who say they didn’t know what Epstein was doing,” she writes. “Anyone who spent any significant amount of time with Epstein saw him touching girls.” She continues: “They can say they didn’t know he was raping children. But they were not blind.”

Review: Nobody’s Girl: A memoir of surviving abuse and fighting for justice – Virginia Roberts Giuffre (Doubleday)

Four days before the memoir was published, Prince Andrew announced he would no longer use the titles conferred upon him, including Duke of York. Three days later, leaked emails from 2011 suggested he gave Giuffre’s date of birth and social security number to one of his protection officers, hours before the infamous photograph of him with her was published.

Maxwell’s brother, Ian Maxwell, published an article in the Spectator today, headlined “Don’t take Virginia Giuffre’s memoir at face value”. The memoir keeps his sister, who was convicted of charges including sex trafficking of a minor, in world headlines – at a time Donald Trump has said he will “take a look” at pardoning her. Earlier this year, Maxwell was moved to a lower security prison to continue her 20-year sentence.

Allegations of parental abuse

Giuffre writes that her father began molesting her at the age of seven. He “strenuously” denies this. While the memoir makes this public for the first time, Giuffre’s older brother Danny Wilson told ABC’s 7.30 he first heard the allegations years before the memoir was published – and confronted his father about it.

Giuffre regularly wet her pants at school – earning her the cruel nickname “Pee Girl”. She recalls: “I began to get painful urinary tract infections. My infections were so severe, I couldn’t hold my urine.”

After one (of several) medical examinations, a doctor told her mother her primary school aged daughter’s hymen was broken. Giuffre writes of this moment:

My mother didn’t hesitate. ‘Oh, she rides horses bareback,’ she explained. That was the end of that. I didn’t even know what a hymen was.

Later, she recalls her mother raising suspicions about her involvement with Epstein and “apex predator” Maxwell, questioning “what this older couple wanted with a teenage girl who had no credentials”.

Giuffre writes: “I guess I was glad she cared enough to have suspicions, but at the same time, wasn’t it a little late for that? I knew she couldn’t save me; she’d never saved me before.”

Around the time of her doctor’s visit, the memoir alleges, Giuffre’s father began “trading” his daughter to a friend – a tall, muscular man with “a military bearing” who was also abusing his own stepdaughter. In 2000, the man was convicted of molesting another girl in North Carolina. He spent 14 months in prison and a decade as a registered sex offender.

Giuffre writes that she was abused by these men for five years, from ages seven to eleven; it only stopped when she began menstruating.

Heartbreakingly, Giuffre discloses that at one point she imagined Maxwell (or “G-Max” as she wanted to be known) as her mother: “While I was hardly equipped to judge, it often seemed to me that Epstein and Maxwell behaved like actual parents.” Among other things, the pair gave Giuffre her first cell phone, whitened her teeth, and taught her how to hold a knife and fork “just so”.

‘The younger, the better’

Giuffre’s memoir is a courageous and clear-eyed account of what trauma takes – and what recovery demands.

Told in four chronological parts – “Daughter”, “Prisoner”, “Survivor” and “Warrior” – the memoir meticulously records the “sexual assaulting, battering, exploiting, and abusing” Giuffre endured throughout her life, most notably at the hands of Epstein and Maxwell.

The result is a devastating exposé of the fetishisation and abuse of girls – “the younger, the better”, Epstein said – and society’s failure to protect the most vulnerable.

It is also a damning indictment of everyone who knew and looked away.

‘Please don’t stop reading’

Giuffre was 16 and working as a locker-room attendant at Trump’s Mar-a-Lago resort when Ghislaine Maxwell recruited her to “service Epstein”, under the pretence of training as a masseuse. (In October 2007, Trump – who is portrayed favourably in the memoir – reportedly banned Epstein from his resort after Epstein hit on the teenage daughter of another member.)

Over the next two years, and roughly 350 pages, Giuffre tells how she was trafficked to “a multitude of powerful men”, including Prince Andrew, French modelling agent Jean-Luc Brunel, a prominent psychology professor and a respected United States senator.

Giuffre’s original memoir manuscript was titled “The Billionaire’s Playboy Club”.

In one of the most distressing scenes, Giuffre describes how she was trafficked to “a former minister”, who raped her so “savagely” she was left “bleeding from [her] mouth, vagina, and anus”. When Virginia told Epstein about the brutal attack, which made it hurt to breathe and swallow, he said, “You’ll get that sometimes.”

Eight weeks later, he returned Giuffre to the politician, who this time abused her on one of Epstein’s private jets. In the US version of the memoir, the politician is described not as a “former minister”, but as “a former Prime Minister”.

“I know this is a lot to take in,” Giuffre writes. “The violence. The neglect. The bad decisions. The self-harm. But please don’t stop reading.”

One of the most devastating revelations comes toward the end of the memoir. Giuffre – now in her forties – receives a phone call from a confidant claiming to have evidence that Epstein paid off her father when she was a girl. In 2000, when Epstein and Maxwell started abusing the teenager at El Brillo Way, it is alleged that her father accepted “a sum of money” from the paedophile.

According to Giuffre, when she confronted her father, there was “a brief silence” before “he started yelling at [her] for being an ungrateful daughter”.

Of all the betrayals she endured, this one stands alone: “I will never get over it”.

Girls no one cared about

“When a molester shows his face,” Giuffre writes, “many people tend to look the other way.”

In chapter 11, Giuffre describes how Epstein’s personal chef, the celebrity cook Adam Perry Lang, made her her favourite food – pizza. This, apparently, became something of a tradition – Lang feeding Giuffre, but never “ogl[ing]”, “even if I was standing naked in front of him, which was not unusual”. She wrote: “When I’d finished attending to Epstein or one of the other guests, Lang would have a cheesy hot pie waiting.”

In 2019, Lang issued a statement about working for Epstein: “My role was limited to meal preparation. I was unaware of the depraved behavior and have great sympathy and admiration for the brave women who have come forward.”

In another scene, Giuffre reveals that Epstein “never wore a condom”. After falling pregnant at the age of 17, she suffered an ectopic pregnancy.

On this day, Giuffre recalls how Epstein and Maxwell (“two halves of a wicked whole”) – with the help of Epstein’s New York butler – drove her to hospital after she woke in “a pool of blood”. Epstein lied to the doctor about her age, Giuffre alleges, and the two men seemed to enter “a gentlemen’s agreement” in which “whatever was going on between this middle-aged man and his teenage acquaintance […] would be kept quiet”.

“We were girls who no one cared about, and Epstein pretended to care,” Giuffre writes. “At times I think he even believed he cared.” She describes how Epstein “threw what looked like a lifeline to girls who were drowning, girls who had nothing, girls who wished to be and do better.” As a self-described “pleaser” who “survived by acquiescing”, Giuffre writes that Epstein and Maxwell “knew just how to tap into that same crooked vein” her childhood abusers had: abuse cloaked in “a fake mantle of ‘love’.”

Sex as birthright

In March 2001, at Maxwell’s upscale townhouse in London’s Belgravia – where Prince Andrew was famously pictured with his arm around the teenager – Giuffre recalls how Maxwell invited Andrew to guess her age. When the prince correctly guessed 17, he reportedly told her, “My daughters are just a little younger than you.”

Later that night, she writes, Prince Andrew bought the teenager cocktails at Tramp – an exclusive London nightclub – where she and the prince danced awkwardly and the prince “sweated profusely”. In the car, on the way home, Maxwell instructed Giuffre “to do for [Andy] what you do for Jeffrey”.

In November 2019, in his calamitous interview with BBC’s Newsnight, Prince Andrew denied any wrongdoing, claiming he had “no recollection of ever meeting this lady”. He told presenter Emily Maitlis he could not have danced sweatily at Tramp because he had “a peculiar medical condition” that prevented perspiration, caused by what he described as “an overdose of adrenaline” in the Falklands War.

In that interview, Andrew admitted his decision to stay at Epstein’s New York home in December 2010 – months after Epstein was released from jail for soliciting and procuring minors for prostitution – was “the wrong thing to do”. However, the prince claimed his decision was “probably coloured by [his] tendency to be too honourable”.

In her memoir, Giuffre describes Andrew as “friendly enough but entitled” – “as if he believed having sex with [her] was his birthright.” She alleges she had sex with the prince on two more occasions.

The last word

Publishing a book posthumously can be an ethical minefield. Critics often question whether posthumous publication is what the author would have wanted. They point to the author’s right to protect their work and their literary reputation – a right that cannot survive them.

However, Giuffre left no space for speculation. In the email she sent her co-author and publicist before her death, she made her wishes clear:

It is my heartfelt wish that this work be published, regardless of my circumstances at the time. The content of this book is crucial, as it aims to shed light on the systemic failures that allow the trafficking of vulnerable individuals.

As the memoir progresses, Giuffre’s health spirals. The physical, emotional and mental toll of trauma closes in on her. Epstein is dead. Maxwell is in prison. But Giuffre is still “trapped in an invisible cage”.

“From the start,” she says, “I was groomed to be complicit in my own devastation. Of all the terrible wounds they inflicted, that forced complicity was the most destructive.”

Before she died, Giuffre made a promise to her husband and children that she would try with “all her might” to believe her life mattered. Her final goal was to prevent “the emotional time-bomb” inside her from detonating.

While Giuffre may at last be beyond harm, the truth remains. She – like the hundreds of girls abused by Epstein and his associates – was wronged.

Her fight, like theirs, transcends death: release the Epstein files; hold abusers and their enablers accountable; expose the systems that protect predators; abolish statutes of limitations for the sexual abuse of minors. Ensure no other child suffers. This is what Giuffre wanted.

By publishing her memoir, she ensured the fight would survive her. She made certain her voice would outlast her pain.

In this way, she got the last word.

If this article has raised issues for you, or if you’re concerned about someone you know, call Lifeline on 13 11 14.

The National Sexual Assault, Family and Domestic Violence Counselling Line – 1800 RESPECT (1800 737 732) – is available 24 hours a day, seven days a week for any Australian who has experienced, or is at risk of, family and domestic violence and/or sexual assault.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Kate Cantrell, University of Southern Queensland

Read more:

- No longer ‘Prince Andrew’: an expert on how royals can be stripped of their titles

- Prince Andrew’s ‘one peppercorn’ lease exposes how little is known about royal finances

- Kiran Desai’s first novel in nearly 20 years is shortlisted for the Booker. Last time, she won it

Kate Cantrell does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The Conversation

The Conversation

Associated Press US News

Associated Press US News Law & Crime

Law & Crime The Fashion Spot

The Fashion Spot Raw Story

Raw Story ABC 7 Chicago Sports

ABC 7 Chicago Sports