If you’ve been following recent debates about health, you’ve been hearing a lot about vaccines, diet, measles, Medicaid cuts and health insurance costs – but much less about one of the greatest threats to global public health: climate change.

Anybody who’s fallen ill during a heat wave, struggled while breathing wildfire smoke or been injured cleaning up from a hurricane knows that climate change can threaten human health. Studies show that heat, air pollution, disease spread and food insecurity linked to climate change are worsening and costing millions of lives around the world each year.

The U.S. government formally recognized these risks in 2009 when it determined that climate change endangers public health and welfare.

However, the Trump administration is now moving to rescind that 2009 endangerment finding so it can reverse U.S. climate progress and help boost fossil fuel industries, including lifting limits on greenhouse gas emissions from vehicles and power plants. The administration’s arguments for doing so are not only factually wrong, they’re deeply dangerous to Americans’ health and safety.

As physicians, epidemiologists and environmental health scientists who study these effects, we’ve seen growing evidence of the connections between climate change and harm to people’s health. More importantly, we see ways humanity can improve health by tackling climate change.

Here’s a look at the risks and some of the steps individuals and governments can take to reduce them.

Extreme heat

Greenhouse gases from vehicles, power plants and other sources accumulate in the atmosphere, trapping heat and holding it close to Earth’s surface like a blanket. Too much of it causes global temperatures to rise, leaving more people exposed to dangerous heat more often.

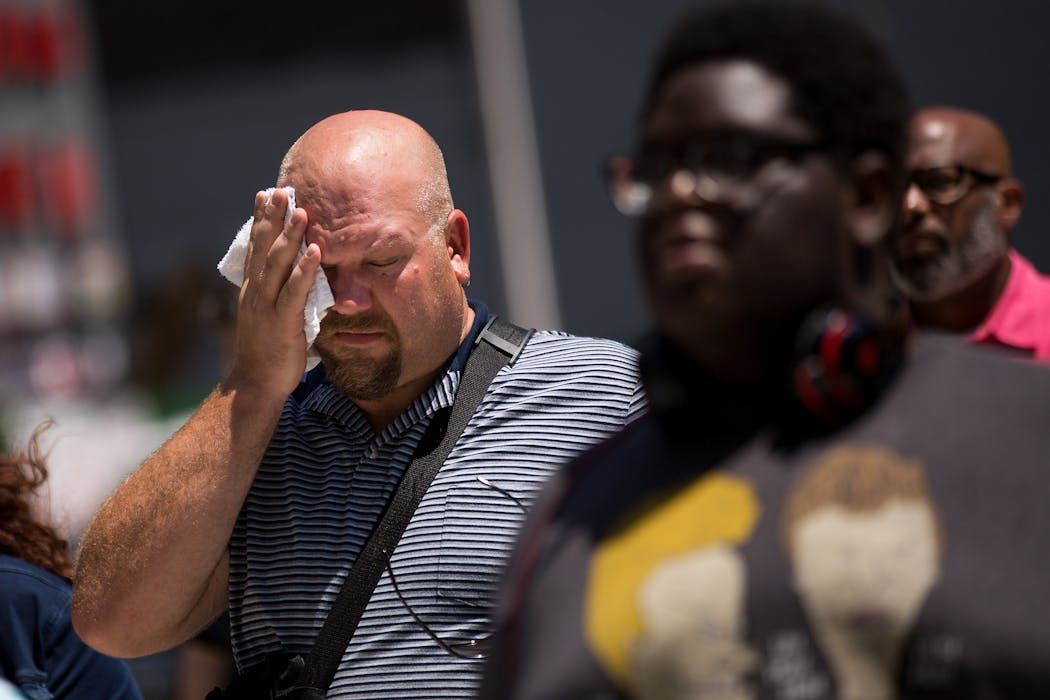

Most people who get minor heat illnesses will recover, but more extreme exposure, especially without enough hydration and a way to cool off, can be fatal. People who work outside, are elderly or have underlying illnesses such as heart, lung or kidney diseases are often at the greatest risk.

Heat deaths have been rising globally, up 23% from the 1990s to the 2010s, when the average year saw more than half a million heat-related deaths. Even in the U.S., the Pacific Northwest heat dome in 2021 killed hundreds of people.

Climate scientists predict that with advancing climate change, many areas of the world, including U.S. cities such as Miami, Houston, Phoenix and Las Vegas, will confront many more days each year hot enough to threaten human survival.

Extreme weather

Warmer air holds more moisture, so climate change brings increasing rainfall and storm intensity, worsening flooding, as many U.S. communities have experienced in recent years. Warm ocean water also fuels more powerful hurricanes.

Increased flooding carries health risks, including drownings, electrocution and water contamination from human pathogens and toxic chemicals. People cleaning out flooded homes also face risks from mold exposure, injuries and mental distress.

Climate change also worsens droughts, disrupting food supplies and causing respiratory illness from dust and dry conditions as well as wildfires. And rising temperatures and aridity dry out forest and grasslands, making them more vulnerable to catching fire, which creates other health risks.

Air pollution

Wildfires, along with other climate effects, are also worsening air quality around the country.

Wildfire smoke is a toxic soup of microscopic particles (known as fine particulate matter, or PM2.5) that can penetrate deep in the lungs and hazardous compounds such as lead, formaldehyde and dioxins generated when homes, cars and other materials burn at high temperatures. Smoke plumes can travel thousands of miles downwind and trigger heart attacks and elevate lung cancer risks, among other harms.

Meanwhile, warmer conditions favor the formation of ground-level ozone, a heart and lung irritant. Burning of fossil fuels also generates dangerous air pollutants that cause a host of health problems, including heart attacks, strokes, asthma flare-ups and lung cancer.

Infectious diseases

Because they are cold-blooded organisms, insects are directly influenced by temperature. So as temperatures have risen, mosquito biting rates have risen as well. Warming also shortens the development time of disease agents that mosquitoes transmit.

Mosquito-borne dengue fever has turned up in Florida, Texas, Hawaii, Arizona and California. New York state just saw its first locally acquired case of chikungunya virus, also transmitted by mosquitoes.

And it’s not just insect-borne infections. Warmer temperatures increase diarrhea and foodborne illness from Vibrio cholerae and other bacteria and heavy rainfall increases sewage-contaminated stormwater overflows into lakes and streams. At the other water extreme, drought in the desert Southwest increases the risk of coccidioidomycosis, a fungal infection known as valley fever.

Other impacts

Climate change can threaten health in numerous other ways. Longer pollen seasons can increase allergen exposures. Lower crop yields can reduce access to nutritious foods.

Mental health can also suffer, with anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress following disasters, and increased rates of violent crime and suicide tied to high-temperature days.

Young children, older adults, pregnant women and people with preexisting medical conditions are among the highest-risk groups. Often, lower-income people are also at greater risk because of higher rates of chronic disease, higher exposures to climate hazards and fewer resources for protection, medical care and recovery from disasters.

What can people and governments do?

As an individual, you can reduce your risk by following public health advice during heat waves, storms and wildfires; protecting yourself against tick and mosquito bites; and spending time in green space that improves your mental health.

You can also make healthy choices that reduce your carbon footprint, such as:

-

Walking, biking or using public transit instead of driving, since more physical activity reduces chronic disease risks.

-

Rebalancing your diet from meat-heavy to plant-forward, which can cut your risk of heart disease and lower greenhouse gas emissions from meat production.

-

Making your home more energy-efficient and opting for electric rather than gas- or oil-powered heating and cooking, which can reduce emissions while improving indoor air quality.

However, there are limits to what individuals can do alone.

Actions by governments and companies are also necessary to protect people from a warmer climate and stop the underlying causes of climate change.

Workplace safety can be addressed through rules to reduce heat exposure for people who work outdoors in industries such as agriculture and construction. Communities can open cooling centers during heat waves, provide early warning systems and design drinking water systems that can handle more intense rainfall and runoff, reducing contamination risks.

Governments can ensure that public transit is available and not overly expensive to reduce the number of vehicles on the road. They can promote clean energy rather than fossil fuels to cut emissions, which can also save money since the cost of solar energy has dropped spectacularly. In fact, both solar and wind energy are less expensive than fossil fuel energy.

Yet the U.S. government is currently going in the opposite direction, cutting support for renewable energy while subsidizing the fossil fuel industries that endanger public health.

To really make America healthy, in our view, the country can’t ignore climate change.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Jonathan Levy, Boston University; Howard Frumkin, University of Washington; Jonathan Patz, University of Wisconsin-Madison, and Vijay Limaye, Universi

- Extreme heat and air pollution can be deadly, with the health risk together worse than either alone

- 58% of human infectious diseases can be worsened by climate change – we scoured 77,000 studies to map the pathways

- West Nile virus season returns − a medical epidemiologist explains how it’s transmitted and how you can avoid it

Jonathan Levy receives funding from the National Institutes of Health, the Federal Aviation Administration, the City of Boston, and the Mosaic Foundation.

Howard Frumkin has no financial conflicts of interest to report. He is a member of advisory boards (or equivalent committees) for the Planetary Health Alliance; the Harvard Center for Climate, Health, and the Global Environment; the Medical Society Consortium on Climate Change and Health; the Global Consortium on Climate and Health Education; the Yale Center on Climate Change and Health; and EcoAmerica’s Climate for Health program—all voluntary unpaid positions.

Jonathan Patz receives funding from the National Institutes of Health. He is affiliated with the Medical Society Consortium for Climate and Health, and its affiliate Healthy Climate Wisconsin.

Vijay Limaye is affiliated with the Natural Resources Defense Council.

The Conversation

The Conversation The Texas Tribune Crime

The Texas Tribune Crime

Local News in North Carolina

Local News in North Carolina Local News in Iowa

Local News in Iowa AlterNet

AlterNet Associated Press US and World News Video

Associated Press US and World News Video WKOW 27

WKOW 27 Associated Press Top News

Associated Press Top News Gossip Cop

Gossip Cop Mediaite

Mediaite