From causing a major phone outage to shutting down street lights across parks, suburbs and roads, copper theft has become a clear public safety risk.

Last week, Optus said a phone and mobile data outage that affected more than 14,000 people across south-east Melbourne was triggered by thieves trying to steal copper – and accidentally cutting the wrong cable.

Across the border, last month the South Australia government introduced a bill to crack down on scrap metal theft, particularly copper. That followed more than 2,000 scrap metal thefts from building sites in 2023-24, costing an estimated A$70 million a year – just in one state.

But why are people stealing copper? And what’s being done to stop it?

Why copper is so attractive to thieves

Copper theft has become a multi-billion problem worldwide. In Australia, thieves have recently gone as far as stealing copper memorial plaques from cemeteries.

Back in 2011, an Australian Institute of Criminology tipsheet described scrap metal theft as

a lucrative and attractive venture for thieves and a significant issue for the construction industry.

Scrap metal theft covers a range of metals including copper, steel, lead and aluminium. For instance, catalytic converters are sometimes stolen from cars so criminals can access the palladium, rhodium and platinum in them.

Overseas, a 2024 report found metal theft was costing the United Kingdom’s economy around £480 million (A$970 million) a year.

Scrap metals are among the world’s most recycled materials because of their wide availability. They can be sold to a scrap metal dealer, who then arranges for the metal to be melted and moulded for different uses.

Copper can be recycled again and again, without degrading in the process.

How rising copper prices can drive up thefts

A 2022 systematic review of how changing prices affect the rates of theft for different goods found a 1% increase in the price of a metal can be associated with a 1.2% increase in its theft.

Other past research has also shown that link. For instance, a 2014 UK study showed changes in the price of copper led to more recorded thefts of copper cable from British railways between 2006 and 2012.

The price of copper crashed in 2017 due to factors including a Chinese ban on scrap copper imports. But it has been rising again over the last five years, making it a more attractive target for criminals looking for a quick profit.

Australia’s patchwork response to costly thefts

Police have different powers in different states to tackle copper theft. And this lack of national coordination is part of the problem, as a 2023 Queensland inquiry found.

New South Wales first introduced a Scrap Metal Industry Act in 2016 to target its “largely unregulated and undocumented” scrap metal trade, which it said was “extremely attractive to criminals as a way to make some quick cash”. NSW also tightened its rules and penalties last year.

Victorian scrap metal businesses must also be registered, though under different rules. As in NSW, they’re banned from paying or receiving cash for scrap metal.

Last month, South Australia passed its Scrap Metal Dealers Bill, though it’s yet to come into force. It will give new powers to authorised officers to search, seize and remove evidence – aiming to make it harder to trade in stolen scrap metal.

In Queensland, during the 2024 election campaign, the Liberal National leader (now premier) David Crisafulli promised a legislative crackdown on metal theft.

That’s yet to happen. But the LNP government told the ABC last month it was “committed to cracking down on metal theft and is progressing that work”.

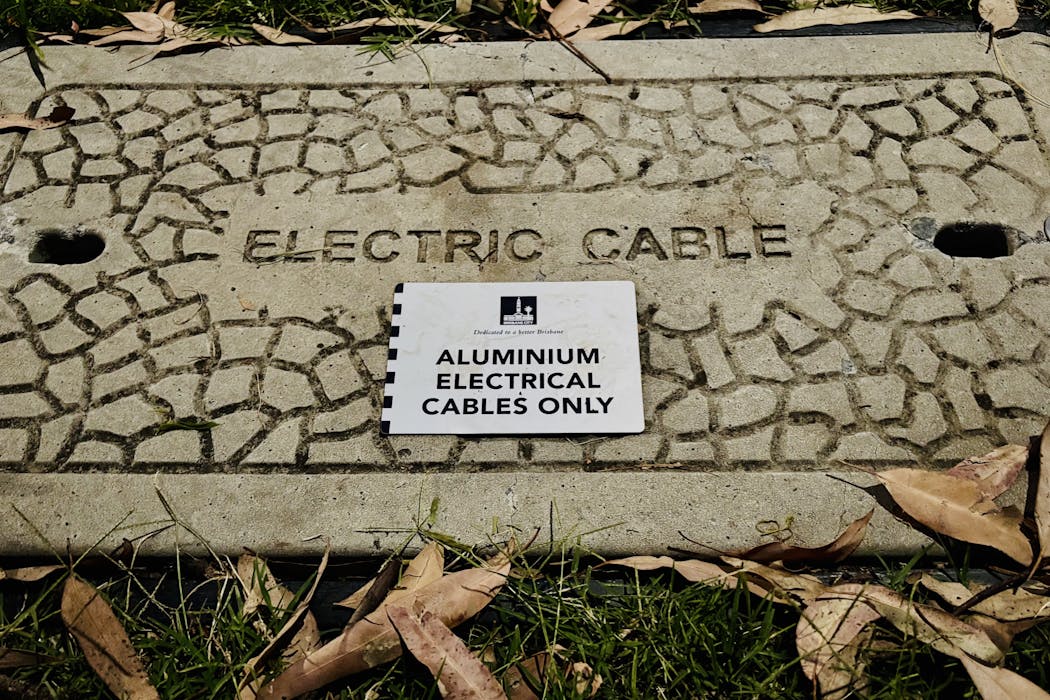

Copper theft has been costing Queensland’s state-owned electricity distribution operators about $4.5 million every year – prompting them to replace thousands of kilometres in underground and overhead copper cabling across southeast Queensland with less valuable aluminium.

A 2023 Queensland parliamentary committee inquiry into scrap metal theft heard that about 200 to 250 scrap metal and car wrecker businesses in Queensland had been operating illegally for years.

The inquiry concluded:

a coordinated approach by all Australian jurisdictions is the best method for combating scrap metal theft. For example, we have heard that stolen goods may be transported and sold interstate. Additionally, we have heard from industry stakeholders that stolen goods are being exported in shipping containers to international destinations where regulations are less prohibitive than in Australia.

Until we get a more coordinated approach, we can all play a role in stopping public thefts of scrap metal, particularly copper.

If you see someone acting suspiciously near electricity infrastructure or a building site, you can report it to police in your state or territory by calling 131 444.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Terry Goldsworthy, Bond University

Read more:

- Huge amounts of plastic waste goes unnoticed – here’s what to do about it

- How the plastics industry shifted responsibility for recycling onto you, the consumer

- Ecoball: how to turn picking up litter into a game for kids

Before joining Bond University, Dr Terry Goldsworthy served with the Queensland Police for 28 years, up to Detective Inspector, from 1985–2013.

The Conversation

The Conversation

Local News in D.C.

Local News in D.C. People Top Story

People Top Story Daily Voice

Daily Voice AlterNet

AlterNet CBS News

CBS News Healthcare Dive

Healthcare Dive IMDb TV

IMDb TV People Food

People Food