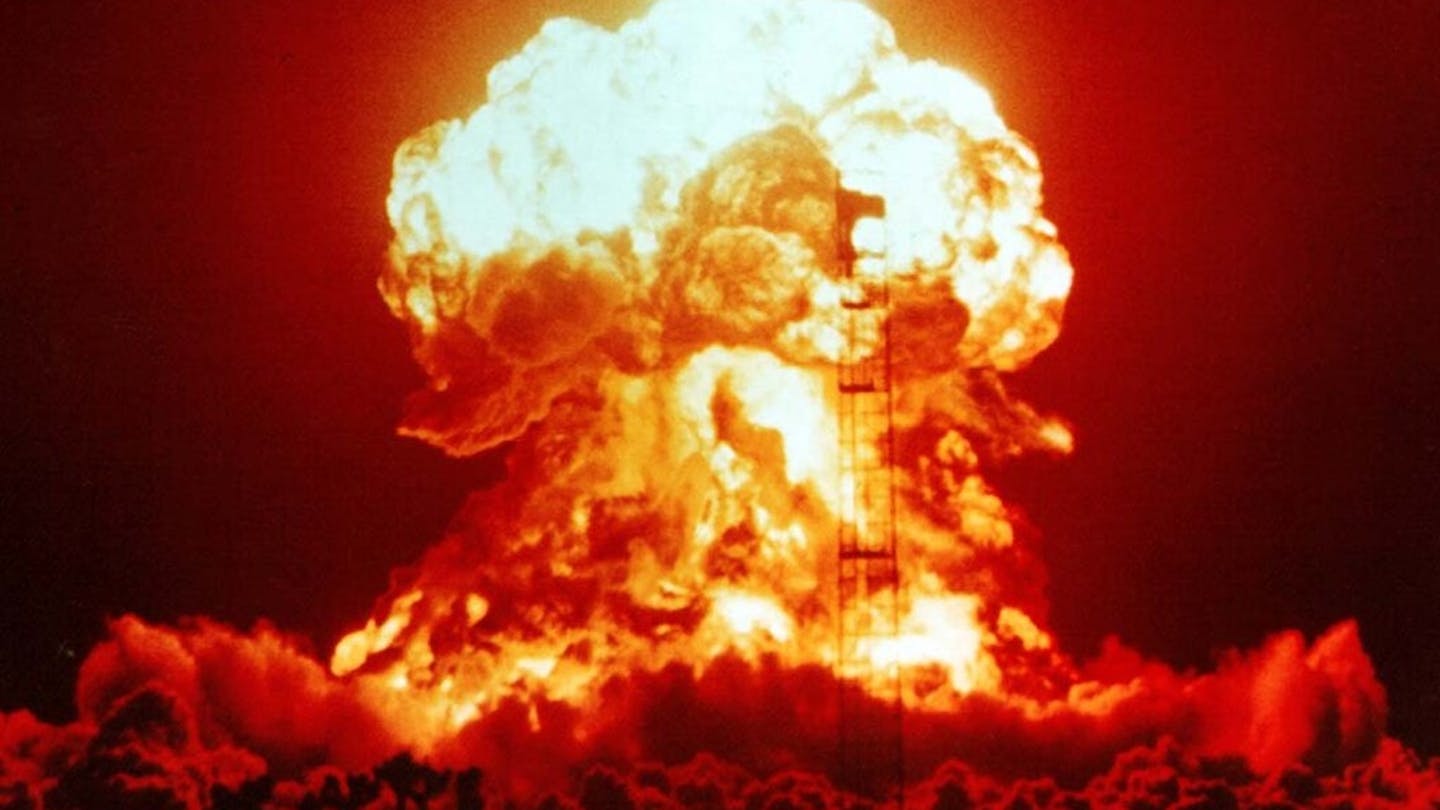

In August 1945 the United States dropped atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, killing more than 200,000 people, overwhelmingly civilians. Eighty years on from this slaughter – which the then US army commander and later president Dwight D. Eisenhower called “completely unnecessary” – is an apt time to ask how the world has changed since Japan’s skies lit up with atomic fire.

Many in the military as well as academics and nuclear theorists argue that a “third nuclear age” has begun. By this they mean that a new and different set of nuclear threats are emerging which fundamentally challenge the existing tenets of nuclear “deterrence”. The response, some argue, is to invest heavily in our nuclear weapons systems to secure ourselves against this new age of uncertainty.

To understand this claim, it’s worth looking back at the history of the nuclear era. Most (but not all) scholars working on “nuclear ages” accept that the first nuclear age, between 1945 and 1991, was characterised by the cold war nuclear stand-off between the world’s two nuclear armed superpowers: the US and the Soviet Union.

The second nuclear age, from 1991 to 2014, is usually understood to have started when the cold war ended. Policymakers worried about “proliferation” – the spread of nuclear weapons to new states and even non-state terrorist groups. Western policy focused on countering this process, often through military means.

The third nuclear age, which is thought to have begun in 2014, it thought to reflect a new set of challenges. This will involve the entry of more nuclear-armed states into the fray, erosion of longstanding non-proliferation and arms control agreements and the development of so-called “strategic non-nuclear weapons”. This term refers to non-nuclear technologies, including artificial intelligence (AI) command and control networks, hypersonic missiles and advanced missile defence systems.

There are fears that non-nuclear armed “adversaries” might use these systems to directly attack other states’ nuclear arsenals, undermining their ability to deliver a retaliatory nuclear strike. This is likely to pose a challenge to established practices on which the doctrine of nuclear deterrence is based.

But how much has really changed in the past decade? No new nuclear powers have emerged – the most recent was North Korea in 2006. China, often seen as the bogeyman of the third nuclear age, has had a nuclear weapons capability since 1964. AI integration into nuclear command and control systems, while extremely risky, has yet to happen.

Reliable missile defence against modern nuclear warheads is still widely considered to be technologically impossible. The impact of hypersonic missiles on the calculus of nuclear deterrence is debated, since intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) are already very fast.

In short, what’s different this time around?

Western-centric thinking

A more penetrating line of questioning is to ask about the politics underlying the idea of a third nuclear age. Ideas are never neutral, and they shape our understanding of the world. The third nuclear age concept (like that of the second nuclear age before it) came out of the US defence establishment, which was trying to understand how it could remain globally dominant against challenges to its supremacy from China.

The idea has since been filtered through academia and back into the policy world, where it has started to gain “common sense status”: as night follows day, the dawn of the third nuclear age is around the corner. But this is neither objective nor inevitable. It’s a conceptual tool for thinking about nuclear politics in a particular way.

It’s a US-centric perspective reflecting a fear that western dominance of the nuclear arena is under threat. US and allied militaries need to progressively integrate new technologies into their nuclear systems and modernise their arsenals to deal with a “more uncertain” world, ignoring the fact that massive risk and uncertainty have always been a built-in feature of nuclear deterrence strategies.

Here, the biggest threats to nuclear stability come not from the thousands of nuclear warheads held by the established nuclear weapons states, but from would-be disruptors who can threaten nuclear arsenals with non-nuclear systems – echoing old second nuclear age fears about proliferation.

This is why Iran remains a villain of the story alongside China, as we can see from the hyperbole about Iran’s “hypersonic” missile capabilities and how its behaviour gave Israel and the US the excuse to launch “counter-proliferation” strikes against its nuclear facilities in June this year.

It bears repeating that Iran is still not a nuclear-armed state. But the new emphasis placed on non-nuclear technologies in third nuclear age thinking also puts states which don’t even have nuclear programmes in the crosshairs of Iraq-style wars of aggression in the name of “counter-proliferation”.

New arms race

To be crystal clear: the nuclear world is as dangerous as ever. The problem is that third nuclear age thinking, with its focus on supposedly unprecedented disruptions, leads us to think that new solutions are necessary. “Old” ideas about nuclear disarmament become irrelevant, because the instabilities introduced by new technologies supposedly make it impossible for nuclear weapons states to give up their arsenals.

The third nuclear age becomes a conceptual stalking horse for a fresh nuclear arms race.

When the British armed forces chief Admiral Sir Tony Radakin warned of a dawning third nuclear age in December 2024, he was not making a neutral observation. He was arguing for resources to be funnelled into nuclear modernisation at the expense of welfare and healthcare programmes. Today, before any modernisation, Britain maintains a first-strike deliverable total of 31 megatons of nuclear explosive power. That’s more than 2,000 Hiroshimas’ worth of destruction.

So we should be sceptical of this concept. The threat of nuclear annihilation has been with us since August 1945 and comes – as always – from nuclear weapons and the states who operate them.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Tom Vaughan, University of Leeds

Read more:

- The nuclear threat: reflections on the atomic age

- Russia is sparking new nuclear threats – understanding nonproliferation history helps place this in context

- ‘Then the city started to burn, the fires were chasing me’ – 80 years on, Hiroshima survivors describe how the atomic blast echoed down generations

Tom Vaughan does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The Conversation

The Conversation

America News

America News CBS News World

CBS News World AP Breaking News

AP Breaking News Raw Story

Raw Story Reuters US Business

Reuters US Business Associated Press Top News

Associated Press Top News Reuters US Top

Reuters US Top FOX News

FOX News