The Trump administration’s mass deportation campaign has not spared the U.S. agricultural industry, with agents from Immigration and Customs Enforcement frequently raiding farms across the country in search of undocumented workers.

Now, farmers are facing a crisis the administration has helped create: not enough people to pick crops.

On a recent call to CNBC, President Donald Trump said, “We can’t let our farmers not have anybody.” To assure farmers that he had their back despite the immigration raids, he sought to distinguish immigrants he called “criminals” and “murderers” from nonthreatening farm laborers who have been picking crops for years.

To do so, Trump used an old stereotype for farmworkers: “These people do it naturally, naturally.” Trump recounted asking a farmer: “What happens if they get a bad back? He said, ‘They don’t get a bad back, sir, because if they get a bad back, they die.’”

“In many ways, they’re very, very special people,” said Trump, referring to undocumented farmworkers.

Trump is labeling some of the people his administration has targeted for deportation as naturals.

As a historian of American agriculture and labor, I think the Trump administration’s contradictions on farmworkers are part of a long history of idealizing farming in America. It’s a history in which race, nature, exploitation and the very identity of America itself have all been involved.

From Jefferson to Sunkist

Thomas Jefferson, most famous for writing the Declaration of Independence, also declared, “Those who labour in the earth are the chosen people of God.”

Jefferson thought America’s true calling was to be an agrarian nation, for virtuous and independent farmers would also be perfect citizens. But Jefferson didn’t actually get his own hands dirty. He told John Quincy Adams that he “knew nothing” about farming.

The Founding Father Alexander Hamilton, in the musical “Hamilton,” crystallized the critiques against what came to be called “Jeffersonian agrarianism,” which praises agricultural life and the virtues of farmers, but fails to acknowledge it was not the planters who did the backbreaking work: “‘We plant seeds in the South. We create.’ Yeah, keep ranting: We know who’s really doing the planting.”

The image of America built up by white farmers contrasted with a reality that “those who labour in the earth” were often enslaved people. As the cotton empire expanded, so did slavery.

Apologists for this system of inequality argued that the “natural station” of Black people was to be enslaved. Black people were portrayed as natural manual laborers – and by extension, the institution of slavery itself was defended as natural, rather than an abrogation of the “natural rights” promised to all men in the Declaration of Independence.

American agricultural leaders in the early 20th century, as I document in my book “Orange Empire,” adapted these forms of “naturalization” – the process, as developed by cultural theorists, through which man-made things such as racial hierarchies are made to appear natural.

In this naturalizing mode, the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce argued in 1929 that “much of California’s agricultural labor requirements consist of those tasks to which the oriental and Mexican due to their crouching and bending habits are fully adapted, while the white is physically unable to adapt himself to them.”

As I describe in my book, the president of the citrus growers cooperative Sunkist insisted in 1944 that Mexicans “are naturally adapted to agricultural work, particularly in the handling of fruits and vegetables.”

Through this naturalization, racism appeared to be made in nature. Everything in farming – all of the food grown in what author Carey McWilliams called “factories in the field” in his 1939 exposé – was carefully constructed by farmers, their lobbyists and their advertisers to appear natural. That includes the racism and labor exploitation at the heart of it.

While naturalizing workers as evolutionarily adapted to stoop labor, this system all but denied undocumented farmworkers legal access to the other kind of naturalization: becoming full citizens.

So when anti-immigrant ideology sparks ICE raids and deportations, the nation’s farms end up losing the labor they have long relied on.

Whose homeland?

On X, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security has been presenting itself as if it’s on a mission to secure a white homeland. It has posted videos of white people enjoying America’s natural wonders to the tune of Woody Guthrie’s “This Land is Your Land” and paintings that propagandize manifest destiny, the idea that the U.S. is destined to extend its dominion across North America.

Homeland Security recently posted John Gast’s 1872 painting “American Progress” as a “Heritage to be proud of.” It depicts a luminous white goddess flying west over the American landscape, with white farmers plowing the soil beneath, while petrified Native Americans, shrouded in darkness, are being chased from their homelands.

As I and others have pointed out, Homeland Security is using coded messages to affirm white supremacists’ vision of turning America into a white homeland.

On the ground in America today, nonwhite immigrants are fleeing from immigration agents, as if the Gast painting is coming to life. The United Farm Workers union, referring to “videos of agents chasing farm workers thru the field,” says that “workers are terrorized.” One worker said they are “being hunted like animals.”

‘Grounds for dreaming’

Trump told CNBC that he does not believe that “inner city” people can come to the rescue of farmers, whose source of labor has been decimated.

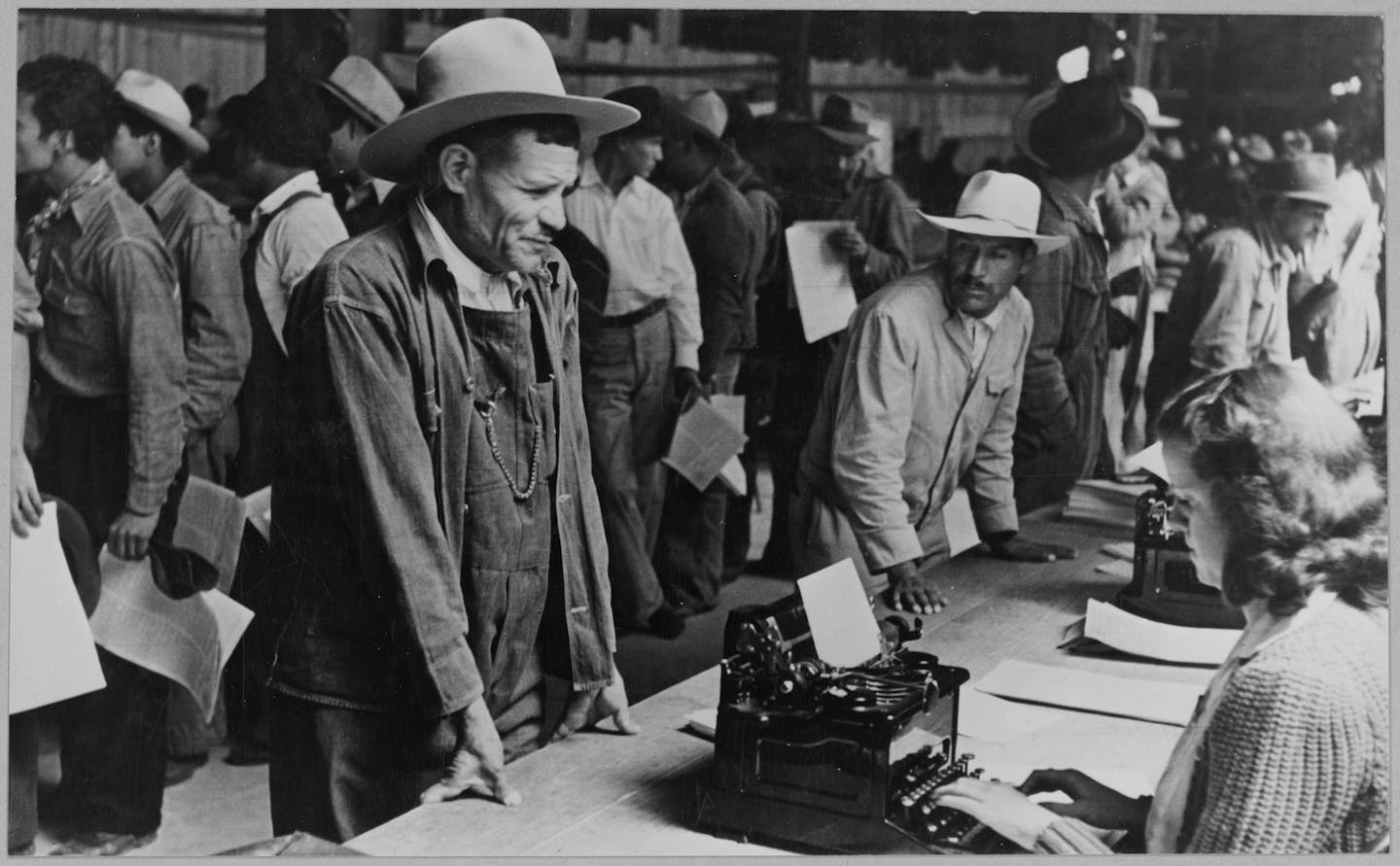

As Politico reports, Trump is now floating the idea of expanding an existing visa program for temporary agricultural workers and creating a new program that requires them to leave the U.S. before reentering legally. If so, he would essentially be reinventing the Bracero Program – the U.S. guest worker program with Mexico created at the behest of California growers during World War II that lasted until the 1960s.

Ian Chandler is an Oregon farmer whose cherries are rotting on the trees because he’s lost the farmworkers who normally pick them. He recently told CNN that these people “are part of our community, just like my arm is connected to my body, they are part of us. So it’s not just a matter of like cutting them off … if we lose them we lose part of who we are as well.”

The Spanish word bracero roughly translates to someone who works with their arms, but the earlier guest worker program didn’t have the same inclusive meaning Chandler intends. Instead, it racialized Mexicans as natural farmworkers, as mere brawn extracted from human beings who were otherwise excluded from the community.

As historian S. Deborah Kang notes, “Sumner Welles, former under secretary of state to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, excoriated the ‘poisoning discriminations’ faced by bracero workers and equated their experiences with the ‘Juan Crow’ racism.”

Over the course of its history, many Americans have held out hope that the U.S. would create a farming nation that lives up to the original promise of an organic democracy – the democracy Jefferson mythologized and one where all Americans are included – built from the ground up.

As historians Camille Guerin-Gonzales and Lori Flores have shown, farmworkers, whatever their official status, have worked hard to find “grounds for dreaming” in America.

Making that American dream a reality involves seeing farmworkers for who they are, I believe: vital members of the body politic who reconnect all Americans to nature through the foods they eat.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Doug Sackman, University of Puget Sound

Read more:

- Providing farmworkers with health insurance is worth it for their employers − new research

- Trump’s push for more deportations could boost demand for foreign farmworkers with ‘guest worker’ visas

- Deporting millions of immigrants would shock the US economy, increasing housing, food and other prices

Doug Sackman does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The Conversation

The Conversation

America News

America News AlterNet

AlterNet Reuters US Top

Reuters US Top Raw Story

Raw Story Cover Media

Cover Media