If you grew up in Australia any time between the 1960s and the late 1990s, chances are you knew a little man from the Moon with a pencil for a nose. His name was Mr Squiggle. Every week he would float down to Earth in his rocket to turn random scribbles into magical drawings.

Mr Squiggle was a ritual for Australian kids. He was a mix of creativity, patience and whimsy that made him one of television’s most unlikely treasures.

Now, more than six decades since his debut, Mr Squiggle is back in the spotlight.

The National Museum of Australia’s Mr Squiggle and Friends: The Creative World of Norman Hetherington is a heartwarming, family-friendly exhibition that pays tribute to one of Australia’s most beloved children’s television icons.

A collection for the National Museum

The 300 items on display are a nostalgic yet vibrant journey rooted in the museum’s 2024 acquisition of 800 items from Mr Squigggle’s creator, Norman Hetherington, donated by his daughter Rebecca.

Hetherington was born in New South Wales in 1921. After graduating high school, he entered art school. During the second world war, Hetherington worked with the Australian Army Entertainment Unit, creating puppets and sketches to entertain troops. This cemented his interest in puppetry as a way of combining humour, imagination and visual storytelling.

After the war, he performed puppet shows in Sydney and refined his craft, eventually blending it with his drawing ability.

Mr Squiggle evolved from short, improvised drawing sessions into a structured and ritualised children’s program, airing on the ABC from 1959.

In the early years, the focus was simply on transforming children’s squiggles into pictures. By the 1970s, supporting characters like Blackboard and Gus the Snail were introduced, giving the show recurring routines. The 1980s brought longer episodes, while the 1990s cemented the familiar sequence of rocket arrival, squiggle drawings, comic banter and return to the moon.

The newly acquired items at the museum include puppets, artworks, scripts, costumes, props, sets and audiovisual material.

A childhood companion

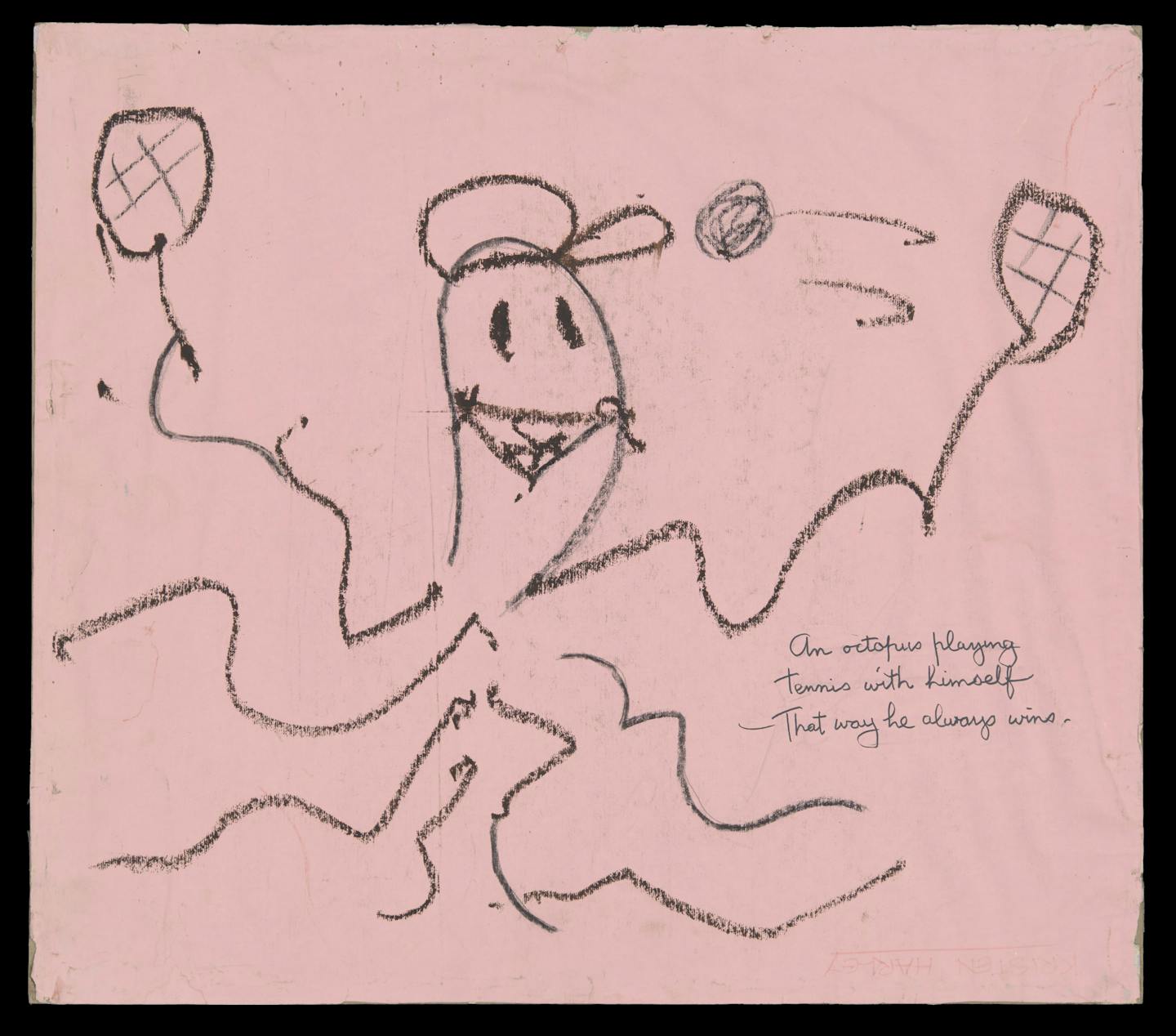

Mr Squiggle worked on a simple but enchanting premise: children mailed in their scribbles, and on air the puppet – controlled and voiced by Hetherington – used his pencil nose to transform them into recognisable drawings.

The exhibition taps directly into the nostalgia of Mr Squiggle. Curators have approached the collection with care, conserving and retouching items and using custom supports and lighting to preserve fragile puppets.

Visitors can view old episodes, try puppeteering and participate in a digital “squiggle” drawing activity that brings scribbles to life. These elements do more than entertain. They capture the ethos of the original program: creativity, play and transformation.

Many of the original sets, crafted from felt and cardboard, are on display along with a selection of the 10,000 squiggles that appeared on the show. The homemade, low-tech and imaginative puppets, sets and squiggles are a joyful reminder you don’t need big budgets or brash American styles to capture children’s imaginations.

A changing Australia

Mr Squiggle reflected Australia. In the 1960s, the country was changing rapidly – suburbs were growing, television was new, and Australians were beginning to have less sentimental attachment to Britain and shaping their own cultural identity.

Mr Squiggle fitted this moment perfectly. Here was a show which featured Australian accents, ideas and images.

Mr Squiggle celebrated imagination, patience and participation. Children weren’t passive viewers. By posting in their drawings, they became part of the show.

The show’s slow pace taught patience, its participatory format showed children their creativity was valued, and its absurd humour encouraged looking at the world from a different angle – sometimes literally upside down.

Seeing the world differently

More than 60 years since its debut, and over 25 years since the last episode aired in 1999, Mr Squiggle continues to encourage us to see the world differently.

For older Australians, he is a reminder of mid-afternoons in front of the television. The show’s afternoon broadcast was likely aimed at children returning from school. For younger ones who didn’t grow up with the show, this exhibition offers an introduction to a different kind of hero: not one who saves the world with superpowers, but one who teaches us to draw, imagine and delight in the ordinary.

Mr Squiggle and Friends: The Creative World of Norman Hetherington is a cultural celebration. It honours Hetherington’s artistry, reconnects Australians with a cherished childhood figure, and shows how a man from the Moon with a pencil nose became part of the nation’s cultural memory.

Mr Squiggle lives on because he occupies a special place in Australia’s cultural memory: a marker of creativity, community and childhood wonder. The National Museum’s exhibition is a celebration of how a lunar puppet with a pencil nose drew his way into Australia’s national story.

Mr Squiggle and Friends is at the National Museum of Australia, Canberra, until October 13.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Jo Coghlan, University of New England

Read more:

- Kangaroo Island is a quietly powerful Australian debut that explores family, grief and belonging

- Werewolf exes and billionaire CEOs: why cheesy short dramas are taking over our social media feeds

- David Stratton was always ‘doing it for the audience’. In this, he had a huge impact on Australian film

Jo Coghlan does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The Conversation

The Conversation

CBS News

CBS News RealClear Politics

RealClear Politics IMDb TV

IMDb TV Page Six

Page Six