Gee I am lonely sweetheart, it may sound silly having so many men and cobbers around me, but when I say lonely I don’t mean lack of company, I am lonely for you, only you can fill the gap in my heart dearest, as each moment passes I seem to miss you and love you more, I shall never get used to living without you […] in fact I am sure we were meant to be together all the time.

My great-grandfather Bill Wiseman wrote this to my great-grandmother Florence in a letter dated October 20 1944.

Aside from when Bill briefly returned on leave from his service for the 2/48 Battalion of the Australian Imperial Force (AIF), he had been separated from Florence since September 1941. Bill would not permanently return to Florence and their children until his discharge from the military on November 8 1945.

It was a long time to be away from his family, and Bill often reflected on the emotional toll their separation had on him.

Loneliness is a common emotion in letters written by Australian service personnel and their loved ones. Rather than a complete physical isolation from others, this situational loneliness was characterised by the absence of a certain person: one’s partner, parents or children.

As Bill acknowledged, while he was surrounded by “cobbers”, it was Florence who he was “lonely for”.

Separations over oceans

Like other historical events that caused mass displacement and separation, the second world war fostered an almost universal sense of situational loneliness.

Emotional experiences and expressions were often dictated by real physical distance. Methods of travel and communication were significantly limited. It could take months for a letter to reach its destination.

Other circumstances influenced how separated families felt and articulated their loneliness in wartime. This could include factors such as how long they had been apart, whether personnel could return home on leave, the intensity of military campaigns which might restrict mail exchanges, and if personnel were injured or captured by enemy forces.

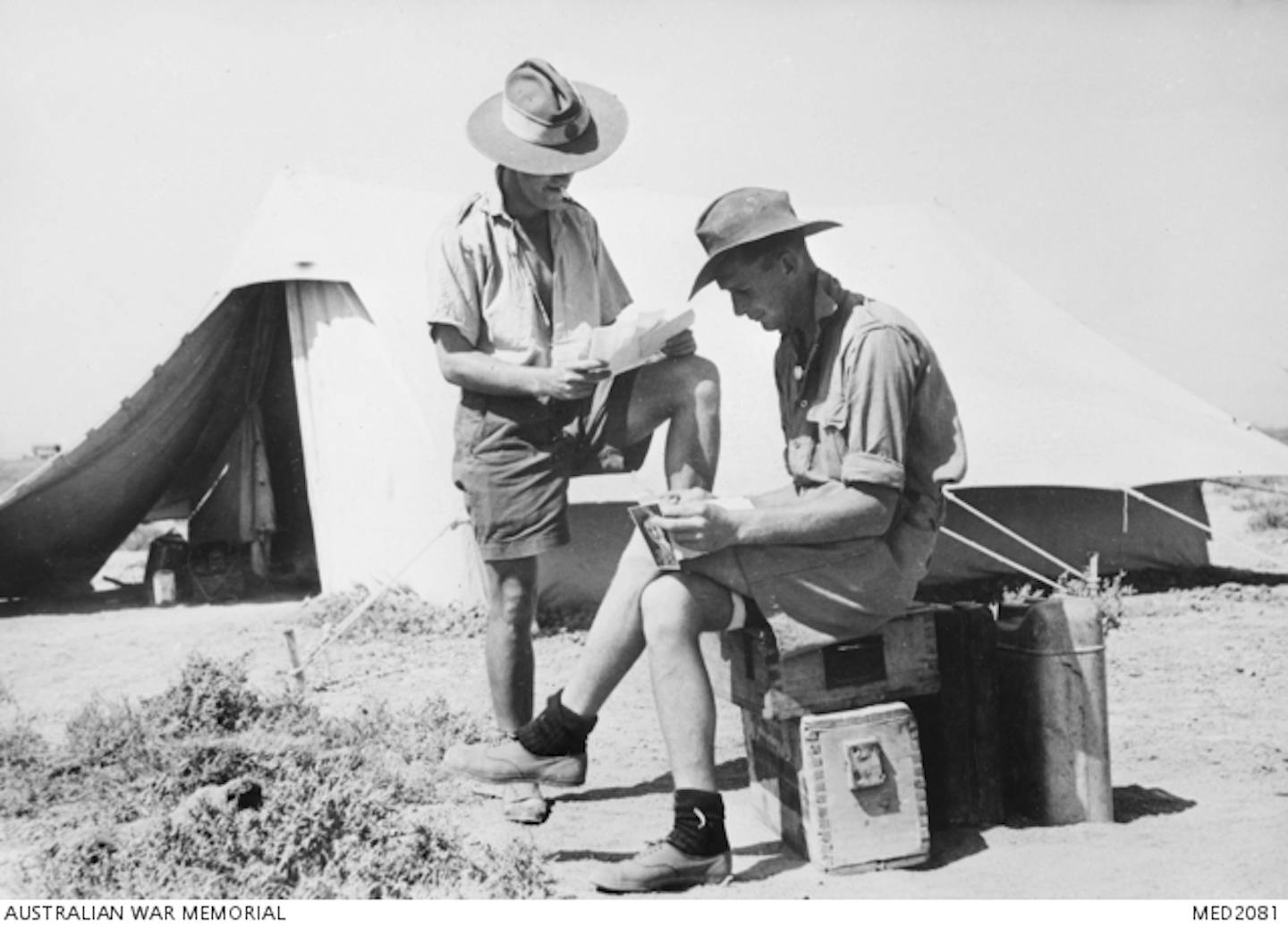

While letters could never completely substitute for the absent person, Australian military personnel and their loved ones recognised the importance of exchanging correspondence to ease their loneliness.

AIF Sergeant Robert Graham implored his fiancée Jane Melrose to write more regularly, as it improved his morale:

I received your ever welcomed and much needed letter yesterday and it made me feel a lot better + miles happier too. Jane whatever you do pleased write as often as you can […] I feel so depressed when mail comes in and I don’t get any from you. It doesn’t matter who I get mail from I’m still not happy unless I recognise your handwriting on the envelope.

Barbara Welbourn, a soil scientist at the University of Adelaide, wrote to her fiancé, Sergeant David Sheppard, about the “renewal” his letters provided when she was lonely:

Your [76th letter] was waiting for me last night; such a blessed end to the day + so longed for […] I am so dependent, my sweet David on your love, its constant renewal, even more wonderful by letters that I will be adrift in sad seas without them.

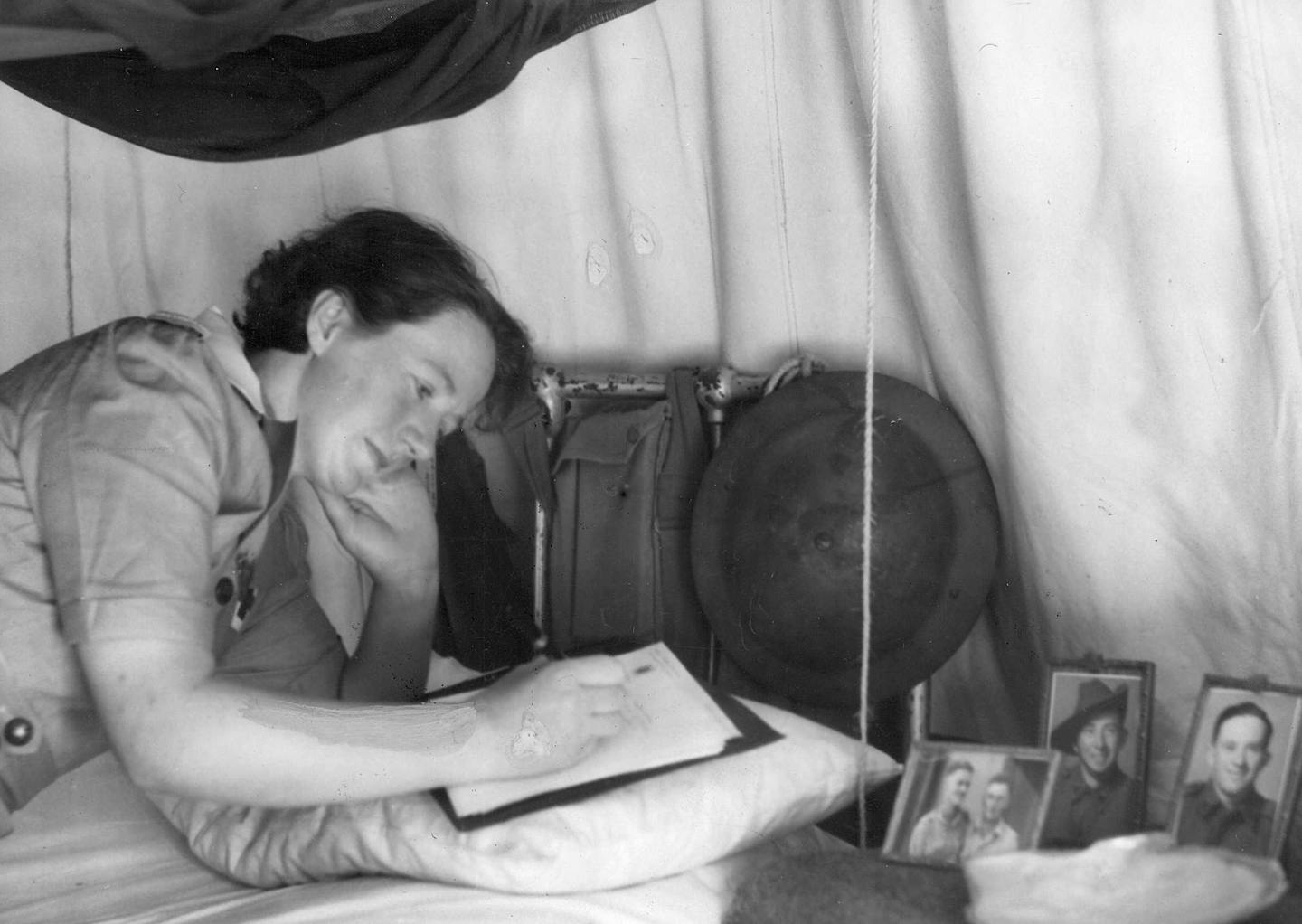

Women’s Auxiliary Australian Air Force Aircraftwoman Doris Plummer wrote she was “dying” for news from her husband Private Walter Plummer, who served in the Volunteer Defence Corps.

She wanted to hear about his Christmas, because as it would make her feel closer their family:

Hope you tell me everyone you saw everything you said and did. How many fish you caught, how many times you swam and missing no details. They are the little unimportant things that make me feel I am not so far away.

Patience and perseverance

While loneliness was (and still often is) perceived as a negative emotion, characterised by mental pain and absence, letter writers from the war often discussed how experiencing these uncomfortable feelings ultimately transformed their relationships for the better.

Albert Gerrard, a private in the Australian Army Medical Corps, assured Margaret James that he believed separation ultimately prepared them for marriage:

Three years have not been wasted, I think we’ve both learned a lot. I have anyway, patience, perseverance, and over + above all else, what a loyal little darling you are. It has also knocked a lot of conceit + selfishness out of me. Generally speaking, I’m better for it.

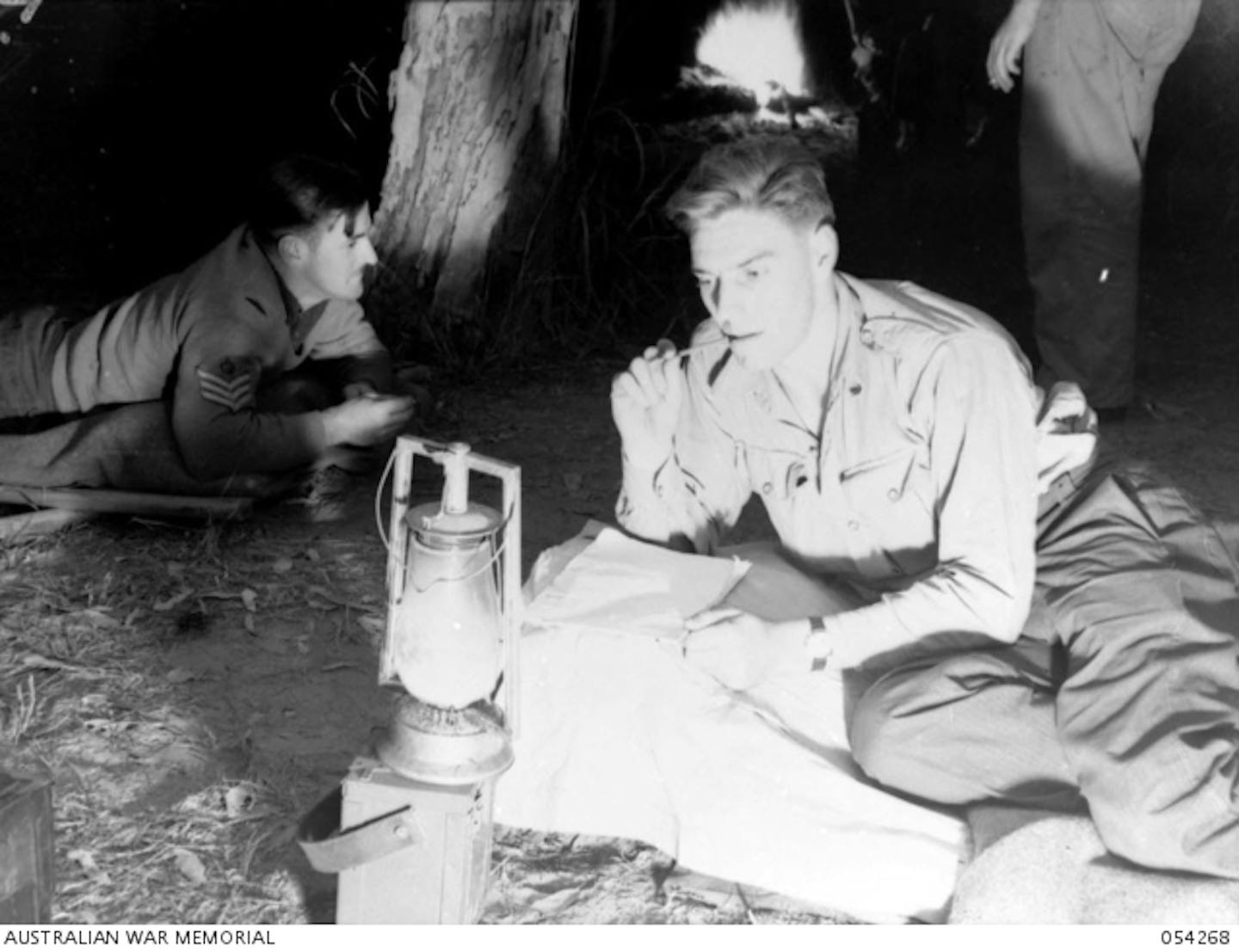

Lance Corporal George Seagrove outlined how he believed the longing he felt for his wife Marjorie made him appreciate the joy she brought him.

In one such letter, George wrote:

This parting, more than anything else, has made me realise how big you have been in my life […] It’s like a soul split in two. When I see anything I always want to rush to my pen and tell you about it. If it is something funny I can hear you laughing because I know you laugh at the same things as I do […] Every day when the mail comes my heart beats a little bit quicker and your familiar handwriting brings a big smile to my face.

Letter writers on the home and battle fronts showed a great capacity to express vulnerability by describing their loneliness.

Through their heartache and anxiety about the uncertainty of their futures, separated spouses realised their love for one another was undeniable.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Emma Carson, University of Adelaide

Read more:

- 80 years since the end of World War II, a dangerous legacy lingers in the Pacific

- How a 300-year-old Scottish country estate escaped the wrecking ball

- The First King of England: Æthelstan and the Birth of a Kingdom – a deep and nuanced analysis of a complex monarch

Emma Carson does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The Conversation

The Conversation

NBC News

NBC News WSAZ NewsChannel 3

WSAZ NewsChannel 3 KCRA News

KCRA News KPLC

KPLC Cowboy State Daily

Cowboy State Daily West Virginia Daily News

West Virginia Daily News San Bernardino Sun

San Bernardino Sun The Takeout

The Takeout Loveland Reporter-Herald

Loveland Reporter-Herald KCRG Iowa

KCRG Iowa