Perennial Nobel Prize contender Thomas Pynchon’s fourth novel, Vineland (1990) has been loosely adapted by Paul Thomas Anderson as a new film, One Battle After Another. The film is already considered an Oscar contender.

Vineland, at its core, is preoccupied with the fate of America in the age of mass media and creeping authoritarianism. Pynchon’s novel is largely set in 1984, the year president Ronald Reagan was reelected in a landslide – a time when the idealism and revolutionary impulses of the American left had withered.

That sense of defeat speaks directly to now. Anderson’s adaptation lands in a year defined by Donald Trump’s decisive 2024 election victory and a MAGA-driven backlash against diversity and inclusion, trans rights and climate action.

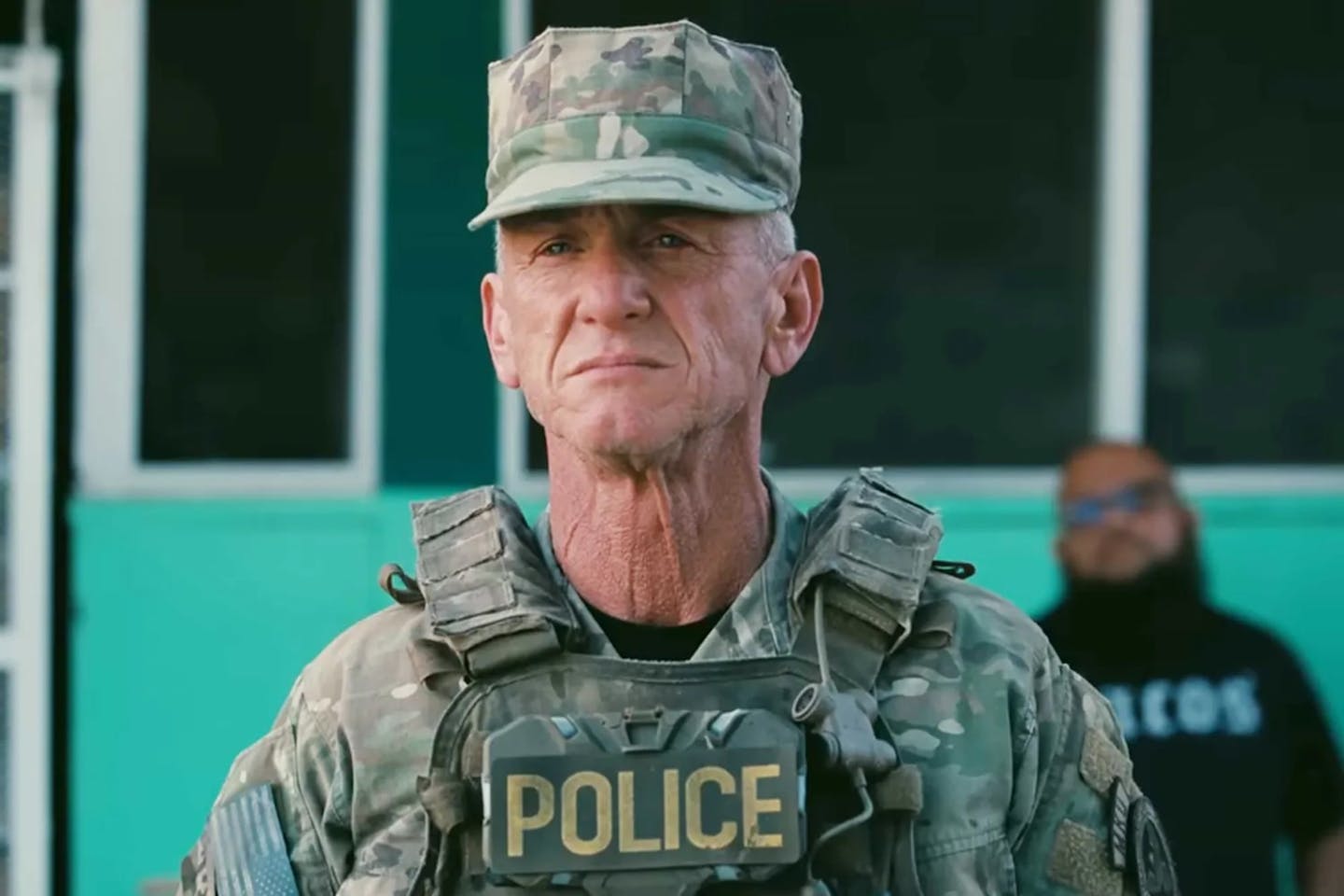

Anderson repurposes Pynchon for our present plight, plunging us into a familiar hellscape of immigration detention centres, white supremacist hideouts and so-called sanctuary cities. One of these cities is a central setting: engulfed in flames, thick with smoke and overrun by state-backed goons kitted out in combat gear – enforcers who seemingly answer to no one, itching to knock a semblance of sense into some “radical left” skulls.

Militarisation of American life

One review of the film points out how the escalation of immigration crackdowns and expansion of ICE under Trump’s second presidency “embodies the militarization of everyday American life” in a way that “feels, in a word, Pynchonian”.

The famously mysterious Pynchon’s last known paid job was a formative stint as a technical writer for Boeing. There, he was “a cog in the US war machine – closely involved in what was the most critical component of the military-industrial complex”, according to American Studies scholar Steven Weisenburger.

Over 100 pages of Pynchon’s Boeing prose survives, including detailed work on intercontinental ballistic missile systems. Tasked with translating the arcane dialect of rocket engineers into readable language for servicemen, Pynchon found himself writing at the very point when the Cuban Missile Crisis brought humanity to the brink of extinction.

This episode left him with a lifelong suspicion of the machinery of mass destruction and the technocratic rationalisations that sustain it.

Vineland: aftershocks of the 1960s

Vineland’s plot focuses on the fallout from the 1960s. It follows washed-up countercultural relic Zoyd Wheeler (Leonardo DiCaprio’s Bob Ferguson in the film) and his teenage daughter Prairie (Chase Infiniti’s Willa), as they navigate the legacy of past betrayals and try to avoid the vice-like grip of state power.

While he changes the names of the characters, Anderson’s film overflows with images and emblems of state repression. In a striking early shot, we see a vast steel wall in the desert, floodlit against the starless night sky. Anderson’s film demonstrates how the shortcomings and failures of past resistance are often replayed, almost note for note, in the present.

Making extensive use of flashbacks and featuring a dizzying array of major and minor characters, Vineland explores the lingering aftershocks of the 1960s and the way they continue to inform personal lives and public culture.

The pot-smoking, welfare-cheque-cashing Zoyd Wheeler is our guide. When we first meet him, Zoyd is scraping by on the margins of Reagan’s America, reminiscing about the old days and trying his best to bring up his daughter.

Looming over them is the absent figure of Frenesi Gates, Prairie’s mother and Zoyd’s former partner, whom they have not seen for years. (In the film, she is represented by the character Perfida Beverley Hills, played by Teyana Taylor.) Once a member of a militant film-making collective (yes, you read that correctly), her camera trained on the frontlines of protest, Frenesi snitched on her comrades and crossed to the dark side.

Her defection is bound up with Brock Vond, a ruthless federal prosecutor, to whom she is disastrously and inexorably drawn. (Sean Penn’s Colonel Steven J. Lockjaw, a detention centre commander, inhabits this role in the film.) Vond is no mere antagonist: seemingly omnipotent, he stands in for Vineland’s vision of state power. Amoral and obsessive, he is the embodiment of a system that brooks no deviation from predetermined norms.

His pursuit of Frenesi is more than a personal fixation; it is an allegory for how the state seduces, compromises and ultimately devours its subjects. This toxic dynamic animates the action of the novel. Pynchon’s point is not simply that the state corrupted Frenesi, but that the left’s own shortcomings and blind spots made such corruption possible in the first place.

In this sense, he is suggesting – correctly – that the seeds of the conservative ascendancy of the late 1970s and 80s were in fact sown in the failures of the radical movements that came before. It is an important, if bitter, pill to swallow – and we can identify comparisons with our own era.

MAGA’s rise has been abetted not only by right-wing mobilisation, but also by the left’s fragmentation: its internal conflicts weakening its ability to resist authoritarian drift in meaningful ways.

This, I think, is one of the reasons Vineland still matters today. Pynchon, to his credit, refuses readers the easy fiction of noble idealism set against the backdrop of a corrupt establishment. Instead, the novel collapses those binaries. Vineland reminds us radical energies can be turned against themselves – and that apparatuses of domination thrive on just such lapses.

In other words, the enduring power of the novel, which ends on a highly ambiguous note, has much to do with its unwillingness to let anyone – least of all those who once dreamed of revolution – off the hook.

Pynchon, conflict and coercion

Pynchon’s reputation rests, to a degree, on work that turns distrust and paranoia into a form of cultural critique. That distrust is already present in his exuberant, globetrotting first novel, V (1963). One of Pynchon’s instantly recognisable signatures – his compendious, darkly comedic writing style – was already present.

His second novel, The Crying of Lot 49 (1966), was shorter and, on the face of it, more accessible. With its paranoid vision of secret postal networks and shadowy conspiracies, it resonated with readers shaken by the turbulence of their historical predicament.

Vietnam. The civil rights struggle. Wave after wave of political assassinations. These were at the forefront of public consciousness, deepening the nagging suspicion that hidden networks of power were shaping events in manners ordinary citizens could neither perceive nor determine.

Published in 1973, Gravity’s Rainbow – a postmodern epic about war, rockets and metaphysics – confirmed Pynchon’s standing as one of the century’s most ambitious novelists. A vast World War II narrative, it centred on the German V-2 rocket as a symbol of technological domination.

For some critics, Vineland seemed like an unsatisfactory retreat from the encyclopaedic scale of Gravity’s Rainbow – into a more straightforward engagement with postwar American society.

But, in fact, it was pivotal in Pynchon’s career. Vineland turns from the manufactured cataclysms of mid-century conflict to more insidious forms of coercion. Personal freedom is drastically curtailed and social existence is managed at every level imaginable. Philosopher Theodor Adorno would describe this as the totally “administered world”.

Read more: Join the Counterforce: Thomas Pynchon's postmodern epic Gravity's Rainbow at 50

Numbed by slop

In Pynchon’s book, the radical upheavals of the 1960s and 1970s cast a long shadow, their energies sometimes tipping into outright political extremism. Yet by (the somewhat Orwellian) 1984, what remains is little more than a desiccated husk of ideological dissent.

It’s easily co-opted into the machinery of late capitalist society, numbed on a steady diet of televisual nothing piped into homes via a device known as the Tube. Meanwhile, an expansive security state relentlessly pursues anyone with the temerity to resist.

Today, instead of the Tube, we are bombarded with algorithmic feeds and AI-generated content, a continual flow of slop designed to pacify and distract us. At the same time, Trump’s return to office has brought renewed efforts to enforce censorship, restrict dissent and crack down on immigration: a 21st-century manifestation of the totalitarian reflex Pynchon outlined so presciently.

In a revealing moment late in Pynchon’s novel, we overhear old-timers somewhere in the background

arguing the perennial question of whether the United States still lingered in a prefascist twilight, or whether that darkness had fallen long stupefied years ago, and the light they thought they saw was coming only from millions of Tubes all showing the same bright-colored shadows.

The world Pynchon warned us about

Given the slow-motion catastrophe of contemporary life, these debates go a long way toward explaining the novel’s enduring relevance. Indeed, they could be lifted almost verbatim from today’s news headlines, where commentators continue to argue whether Trump represents a new sort of fascism or the culmination of an authoritarian tendency long embedded in the fabric of American political life.

One Battle After Another, approximately 20 years in the making, amplifies Pynchon’s concern with how power insinuates itself into every aspect of life. It presents us with a narrative about contemporary America that somehow feels both hyperbolic and, depressingly, only a small step removed from reality.

Unlike Pynchon, who had no problem referencing Reagan in Vineland, Anderson pointedly avoids naming Donald Trump.

Given the current political climate in America, it is probably a sensible choice. (One can only imagine the Truth Social tirade were Trump ever to sit through the film. If it happens, I’ll be online, waiting patiently, with a bag of popcorn and a few small beers.) Still, the event horizon of his second administration marks a gravitational pull too strong to ignore.

Welcome to the world Thomas Pynchon warned us about.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Alexander Howard, University of Sydney

Read more:

- Around the world, migrants are being deported at alarming rates – how did this become normalised?

- The American TikTok deal doesn’t address the platform’s potential for manipulation, only who profits

- How Paraguay became a bastion of conservatism in Latin America

Alexander Howard does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The Conversation

The Conversation

Reuters US Top

Reuters US Top America News

America News AlterNet

AlterNet Raw Story

Raw Story The Daily Beast

The Daily Beast