More than 5,400 cases of malnutrition develop in Australian hospitals each year. This means a patient doesn’t get enough nutrients during their stay for their body’s needs.

Malnutrition delays recovery, increases the risk of complications and readmission, and ultimately pushes older adults into aged care. It’s estimated to cost the health-care system A$240 million each year.

In the community, malnutrition affects about 10% of adults aged 65 and older. But in hospitals, this jumps to around 30–40%.

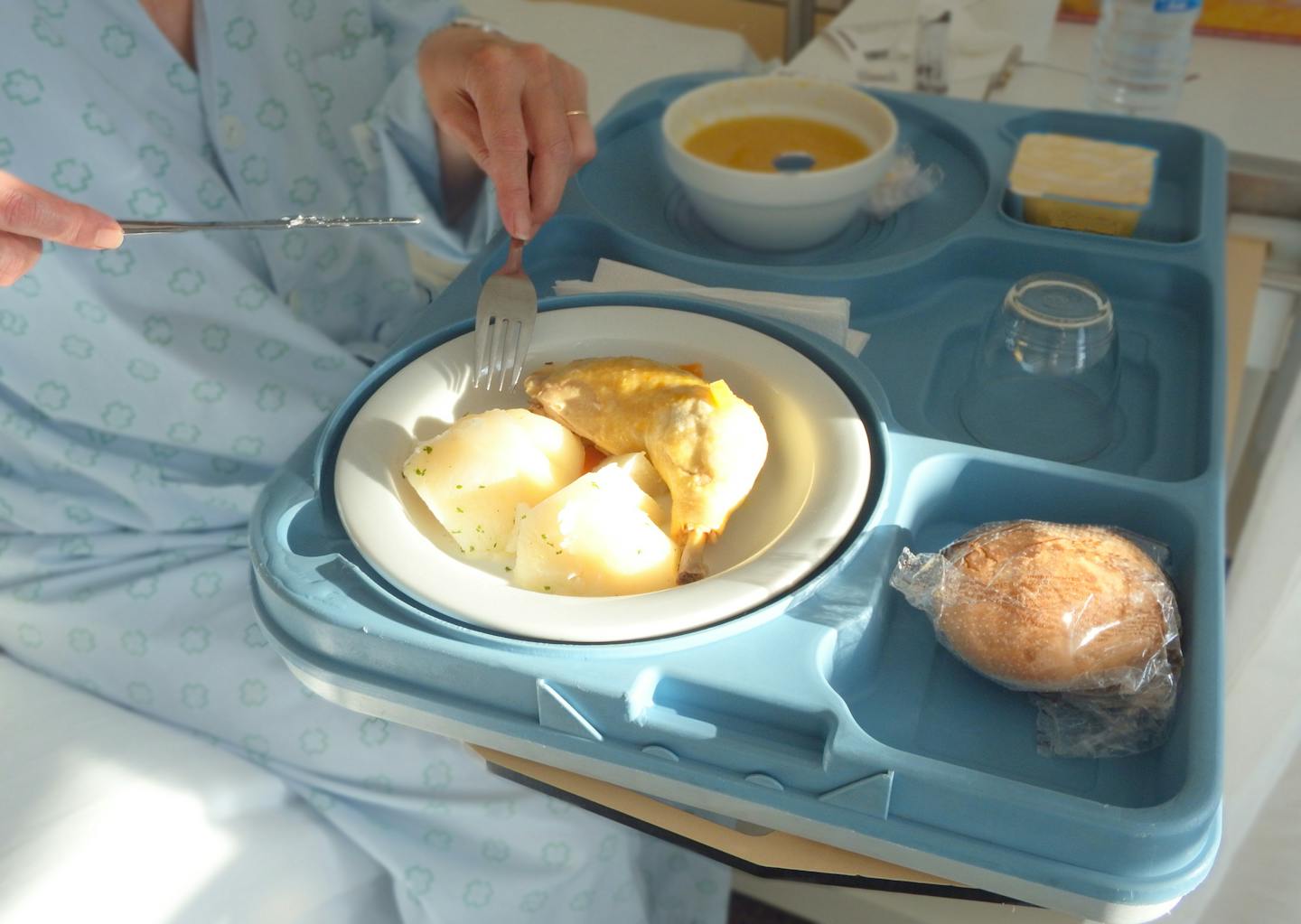

So, why does this happen? It may be because the food is low quality. But malnutrition can also develop when patients are dissatisfied with hospital meals and simply eat less.

In our recent study, we interviewed 30 older patients from Anglo and other cultural backgrounds about their experiences of hospital food.

We found a lack of familiar options can mean people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds don’t eat properly. Here’s why this matters, and what we can do about it.

Patients are diverse – but menus aren’t

Australia’s ageing population is growing fastest among migrants aged 65 and over, especially those from Asia, the Middle East and Sub-Saharan Africa.

Yet hospital meals often fail to reflect their cultural preferences. Australia’s national service standards for health care explicitly mention meeting patients’ nutritional needs, but don’t reference cultural differences.

Public hospital meals are typically “Western-style”: cereals, sandwiches, meat-based mains and desserts. Non-Anglo staples such as rice, pita bread, noodles and even pasta – as well as non-Anglo sauces and desserts – are often missing.

Given the scale of malnutrition in hospitals, understanding older patients’ cultural barriers to eating hospital food is crucial.

Here’s what older patients told us

We interviewed 30 older patients in a large public hospital in Adelaide. Of these, 15 were Anglo-Australian (with an average age of 83) and 15 came from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds (average age 78).

We found both groups shared a “no complaints” attitude and felt the food was “good enough”. People in both groups acknowledged the difficulties hospitals had catering for diverse groups.

But many from non-English speaking backgrounds expressed deeper cultural disconnects that affected how they ate:

Actually it is good. But the problem is that I am not used [to] it. (Ana*, 83, Indo-Fijian)

I just can’t swallow down the flavour. (Sam, 86, Greek)

I prefer if they give me some noodles, but they don’t have any noodles. (Susan, 73, Filipino)

English language barriers also made it hard for some to express dietary needs. Many relied on family members to bring in food from home.

Patients in both groups suggested adding options, rather than changing the whole menu, would help:

It would be nice, just have one option which is coming from different country […] because there’s plenty of people here, not born in Australia. (Jack, 75, Polish)

However some also told us they needed more help to eat:

It’s hard to carry up the food […] because my hand shaking and I lose the food. (Tom, 78, Congolese)

Food satisfaction affects how well you recover

In another study from 2024, we surveyed patients in New South Wales about hospital food and their health.

We spoke to 21,900 adults (with an average age of 60) across 75 public hospitals.

Those who rated hospital food poorly were:

-

2.7 times more likely to be dissatisfied with overall care

-

1.4 times more likely to develop medical complications

-

1.9 times more likely to have delayed discharge.

For non-English speaking patients from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds, the risks were even higher. They were:

-

ten times more likely to be dissatisfied with care

-

three times more likely to have delayed discharge.

So, what would help?

Based on our research, here are four practical steps that could improve care for people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds:

-

Offer more culturally familiar meals: rotate menus and include at least one culturally diverse option per meal.

-

Improve communication: include food service staff from similar cultural backgrounds as in-person interpreters or AI interpreting tools to help patients with limited English express their dietary needs.

-

Train staff to engage: encourage proactive, friendly communication to invite patient feedback and meet cultural and nutritional needs.

-

Screen older people: proactively identify who might be at risk – for example, at GP clinics and during hospital admission – to prevent rather than simply treat malnutrition.

The bottom line

Hospital food isn’t just about nutrition – it’s about care. Making meals more inclusive can improve recovery and reduce costs.

Importantly, it can also enhance quality of life. As one patient in Adelaide told us:

Even when you are in hospital, you are sick, you not only eat to be alive, but eat to have some pleasure. (Jack, 75, Polish)

*Names have been changed to protect patients’ privacy.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Zhaoli Dai-Keller, UNSW Sydney and Yogesh Sharma, Flinders University

Read more:

- More veg, less meat: the latest global update on a diet that’s good for people and the planet

- Reusing medical equipment is good for the planet. But is it safe?

- Australia’s new food security strategy: what’s on the table, and what’s missing?

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The Conversation

The Conversation

Local News in South Carolina

Local News in South Carolina Cover Media

Cover Media FOX 35 Orlando

FOX 35 Orlando America News

America News WKOW 27

WKOW 27 FOX 5 Atlanta Crime

FOX 5 Atlanta Crime Detroit News

Detroit News New York Daily News Snyde

New York Daily News Snyde Hollywood Life

Hollywood Life