When art historian Linda Nochlin famously asked “why have there been no great women artists?” in 1971, her point wasn’t that women lacked talent. It was that the art world had systematically excluded and erased them from history.

In the 50 years since, scholars and curators have worked to reclaim these forgotten women artists. But change has been slow.

The Guerrilla Girls’ activism in the 1980s, the Countess Report’s damning statistics on gender inequality in Australian galleries, and the National Gallery of Australia’s recent Know My Name initiative show the fight for recognition is ongoing.

Dangerously Modern: Australian Women Artists in Europe 1890–1940 marks an exciting new chapter in this project. The new exhibition, from the Art Gallery of South Australia and the Art Gallery of New South Wales, makes a groundbreaking contribution to recovering the stories of overlooked women artists.

Read more: Why weren't there any great women artists? In gratitude to Linda Nochlin

The global stage

With 222 works from 34 collections, Dangerously Modern celebrates the boldness and resilience of the first wave of professional Australian women artists who left for Europe between the turn of the 20th century and the second world war.

They went seeking advanced artistic training and the chance to compete on the global stage. Their time abroad was transformative.

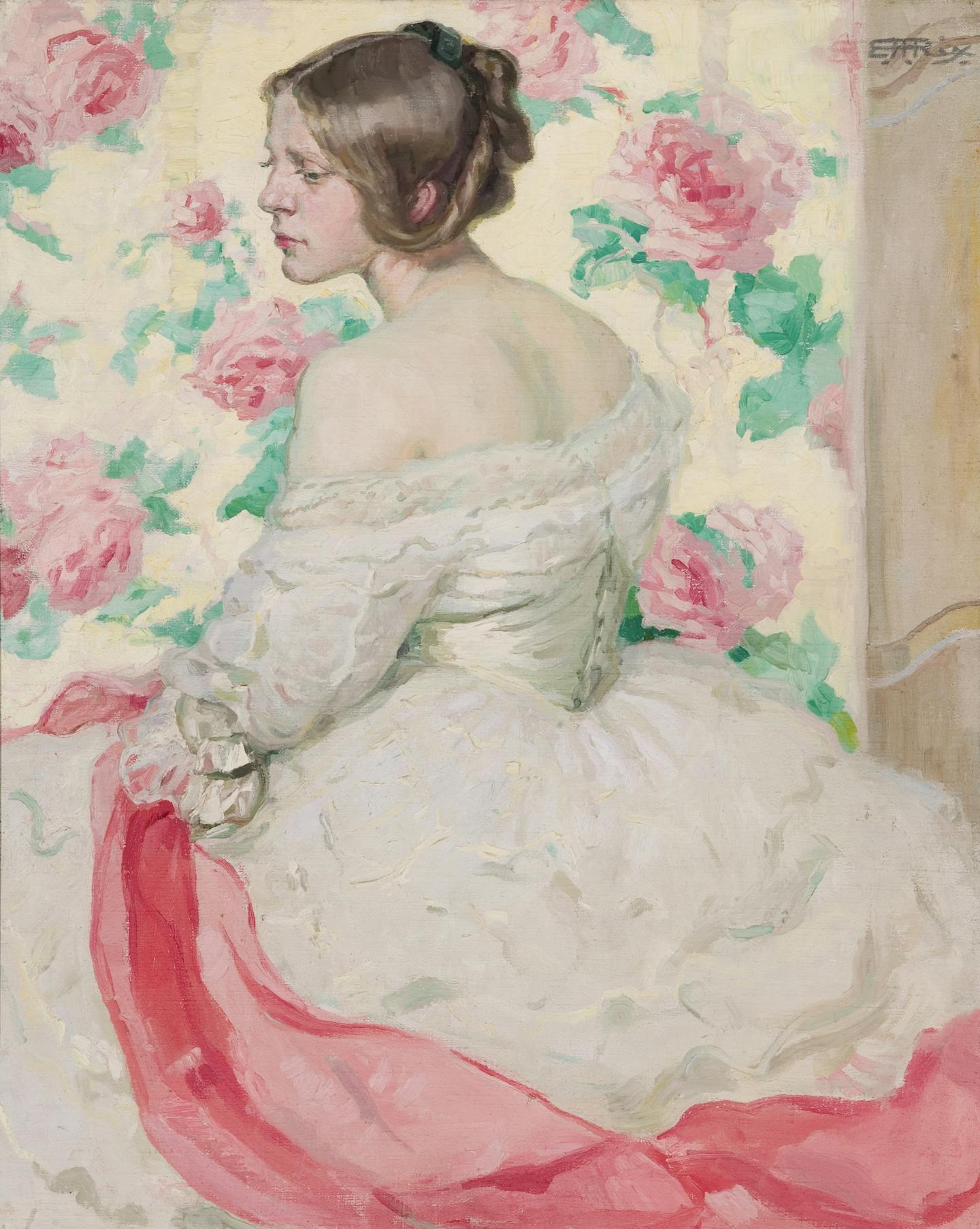

Intimate portraits and domestic interiors by Florence Fuller (1867–1946) and Bessie Davidson (1879–1965) capture moments of quiet reflection. These artists navigated unfamiliar cultures, engaged with cutting-edge artistic movements and built new creative networks.

They lived far from home and maintained connections across two continents – often celebrated in one and forgotten in the other.

The exhibition sheds light on these expatriate artists. They engaged in artistic communities from bustling cosmopolitan centres like Paris and London to regional France, England, Ireland and North Africa.

It reveals the variety of artistic styles in which they worked while weaving together five themes that explore human experience and artistic purpose.

Truly modern

Bold and vibrant paintings by artists like Iso Rae (1860–1940) show their engagement with modern artistic movements.

Through painting en plein air (outdoors) and post-impressionist techniques (using vivid colours and expressive brushstrokes), these women expressed their own experience of modern life. For some, this included portraying their female lovers.

Art can help heal personal trauma. Here, in particular, these women looked at the devastation of war.

The pairing of paintings by Hilda Rix Nicholas (1884–1961) is especially powerful: The Pink Scarf (1913) glows with light, texture and delicate beauty; These Gave the World Away (1917) depicts her husband’s lifeless body on the battlefield.

By retracing the achievements and journeys of 50 expatriate women artists, the exhibition presents works never seen before in Australia. From the celebrated New Zealand artist Edith Collier (1885–1964), Girl in the Sunshine (c.1915) is notable for its bold use of colour, flattened perspective and simplified forms.

It also features works that haven’t been seen in Australia for over a century. A winter morning on the coast of France (1888) by Eleanor Ritchie Harrison (1854–95) was recently rediscovered and donated to the Art Gallery of New South Wales.

The exhibition also reunites works by artist friends who painted side by side.

Women at the forefront

We are privy to moments of breakthrough in these artists’ creativity and careers.

The exhibition brings together landscapes Grace Crowley (1890–1979), Anne Dangar (1885–1951) and Dorrit Black (1891–1951) painted together in 1928 while studying under the French artist André Lhote (1885–1962) in the hilltop village of Mirmande in southeastern France.

These works, to which the artists applied cubist principles (breaking down forms into geometric shapes and showing multiple perspectives), testify to both artistic freedom and each woman’s individual vision and skill.

Though such works placed them at the forefront of French modern art movements, these artists were largely overlooked back in Australia.

Why? At the time, Australia’s conservative art establishment promoted a nationalist agenda. They favoured masculine depictions of labour and Australian landscapes painted by male artists working in Australia.

This elite group marginalised not only women artists but also expatriates who participated in international artistic developments. The resulting nationalist narrative long overlooked the themes this exhibition explores.

Nora Heysen (1911–2003), daughter of celebrated landscape painter Hans Heysen, exemplifies this dual marginalisation. Despite becoming the first woman and youngest artist to win the Archibald Prize in 1938, her self-portraits – which reveal her search for identity and assertion during her London years – remained hidden from public view until the 1990s.

When Thea Proctor (1879–1966) returned to Sydney from London in the 1920s, she wrote, as the catalogue quotes, “it seemed very funny to me to be regarded by some people here as dangerously modern”.

“Dangerously modern” perfectly captures the spirit of the exhibition. These expatriate women artists were seen as threats to tradition, gender roles and to the prevailing definition of what Australian art should be.

Beyond reclaiming the place of these women in the history of Australian art, the exhibition emphasises the importance of migration in shaping artistic identity.

By recognising works created abroad as integral to Australia’s artistic story, this exhibition transforms how we understand both Australian art and modernism as a global movement.

Dangerously Modern: Australian Women Artists in Europe 1890–1940 is at the Art Gallery of New South Wales until February 15 2026.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Victoria Souliman, University of Sydney

Read more:

- Le Carré, Bacchae and radical feminist punk art – what to see and watch this week

- Marie Antoinette Style at the V&A is a rare opportunity to see what survives of the queen’s closet

- Zimbabwean artist Portia Zvavahera turns her prayers into paintings

Victoria Souliman does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The Conversation

The Conversation

WMAR-2 News

WMAR-2 News Raw Story

Raw Story SOFREP

SOFREP FOX 32 Chicago Sports

FOX 32 Chicago Sports Daily Press Sports

Daily Press Sports AmoMama

AmoMama America News

America News AlterNet

AlterNet