In 1844, Berlin was struck by a cultural fever critics labelled Lisztomania.

The German poet Heinrich Heine coined the term after witnessing the almost delirious reception that greeted Hungarian pianist and composer Franz Liszt in concert halls across Europe.

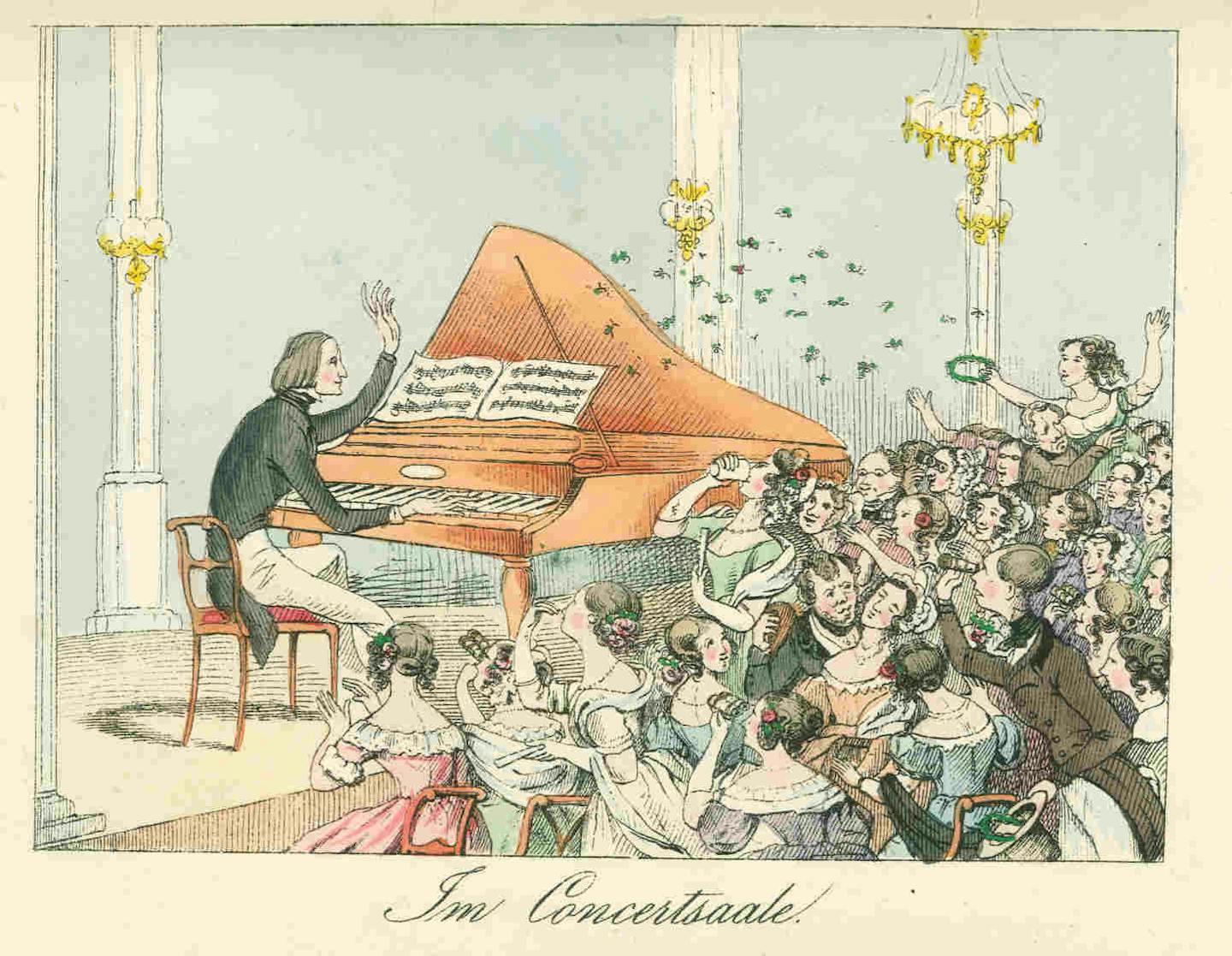

One widely circulated drawing from the 1840s crystallises the image. Women swoon or faint, others hurl flowers toward the stage. Men also appear to be struck by the pianist’s magnetic presence (or perhaps by the women’s reaction to it).

These caricatured depictions, when paired with antagonistic reviews from contemporary critics, may still shape our cultural memory of Liszt.

He is often depicted not simply as a musician but as the first modern celebrity to unleash mass hysteria.

What happened at Liszt’s concerts?

We know a great deal about Liszt’s hundreds of concerts during the 1830s and ‘40s, thanks to reviews, critiques, lithographs and Liszt’s own letters from the time.

His programs combined works by the great composers with his own inventive reworkings of pieces familiar to audiences. Virtuoso showpieces also demonstrated his command of the piano.

Beethoven’s Appassionata Sonata or Pathétique Sonata might appear alongside Bach’s Chromatic Fantasy and Fugue, performed in Liszt’s highly expressive style.

Schubert was represented through songs such as Erlkönig and Ave Maria, reworked for piano alone.

Liszt also turned to the most popular operatic works of his time. His Réminiscences de Norma (Bellini) and Réminiscences de Don Juan (Mozart) transformed familiar melodies into large-scale fantasies. These demanded both virtuosity and lyrical sensitivity.

In these works, Liszt created symphonic structures on the piano. He wove multiple themes into coherent musical dramas far more than simple medleys of well-known tunes.

Liszt often closed his concerts with the crowd-pleaser Grand Galop Chromatique. This encore demonstrated his showmanship and awareness of audience expectations.

As critic Paul Scudo wrote in 1850:

He is the sovereign master of his piano; he knows all its resources; he makes it speak, moan, cry, and roar under fingers of steel, which distil nervous fluid like Volta’s battery distils electrical fluid.

His audience’s response, it would seem, regularly spilled beyond the conventions of polite concert etiquette and social decorum.

Artist and showman

In a series of 1835 essays titled On the Situation of Artists, Liszt presents musicians such as himself as “tone artists”, condemned to be misunderstood. Nevertheless, they have a profound obligation to “reveal, exalt and deify all the tendencies of human consciousness”.

At the same time, a letter to the novelist George Sand reveals Liszt was acutely aware of the practicalities of concerts and the trappings of celebrity.

He jokes that Sand would be surprised to see his name in capital letters on a Paris concert bill. Liszt admits to the audacity of charging five francs for tickets instead of three, basks in glowing reviews, and notes the presence of aristocrats and high society in his audience.

He even describes his stage draped with flowers, and hints at the female attention following one performance, albeit directed toward his partner in a duet.

This letter shows an artist who is self-aware, sometimes amused, and sometimes ambivalent about the spectacle attached to his art.

Yes, Liszt engaged with his celebrity identity, but clearly also felt a measure of distance from it. He was aware the serious side of his art risked being overshadowed by the gossip-column version.

Much of the music criticism of the time functioned in exactly this way. It was little more than the work of gossip writers, many disgusted by the intensity of audience reactions to Liszt’s performances.

Gossip, poison pens, and the making of Lisztomania

Not everyone shared the enthusiasm of Liszt’s audiences. Some critics attacked both his playing and the adulation it provoked.

In 1842, a writer using the pseudonym Beta described the combined effect of Liszt’s performance and the public’s response, writing that:

the effect of his bizarre, substance-less, idea-less, sensually exciting, contrast-ridden, fragmented playing, and the diseased enthusiasm over it, is a depressing sign of the stupidity, the insensitivity, and the aesthetic emptiness of the public.

Similarly, poet Heinrich Heine suggested Liszt’s performance style was deliberately “stage managed” and designed to provoke audience mania:

For example, when he played a thunderstorm on the fortepiano, we saw the lightning bolts flicker over his face, his limbs shook as if in a gale, and his long tresses seemed to drip, as it were, from the downpour that was represented.

These and other accounts fed the mythology of Lisztomania, portraying women in his audience as irrational and hysterical.

The term mania carried a medicalised, pathologising tone, framing enthusiasm for Liszt as a form of cultural sickness.

Lithographs, caricatures, and anecdotal reports amplified these narratives, showing swooning figures, flowers hurled on stage, and crowds behaving in ways that exceeded polite social convention.

Yet these accounts are not entirely trustworthy; they were shaped by prejudice, moralising assumptions, and a desire to sensationalise.

Liszt’s concerts, therefore, existed at a fascinating intersection: extraordinary artistry and virtuosity, coupled with the theatre of audience reception, all filtered through a lens of gossip, exaggeration and gendered panic.

In this sense, the phenomenon of Lisztomania foreshadows the dynamics of modern celebrity. (It was also the subject of what one critic described as “the most embarrassing historical film ever made”.)

Just as performers like the Beatles, Beyoncé and Taylor Swift provoke intense public devotion while simultaneously facing slander and sensational reporting, Liszt’s fame was inseparable from both admiration and the poison pen of his critics.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Timothy McKenry, Australian Catholic University

Read more:

- Taylor Swift’s Father Figure isn’t a cover, but an ‘interpolation’. What that means – and why it matters

- Sacred texts and ‘little bells’: The building blocks of Arvo Pärt’s musical masterpieces

- How Australians are slowly dominating the K-pop music industry

Timothy McKenry does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The Conversation

The Conversation

America News

America News KCRG Iowa

KCRG Iowa FOX News Videos

FOX News Videos The List

The List Washington Examiner

Washington Examiner  Esquire

Esquire