More than 280,000 people have voted for the Top 100 Books of the 21st Century in a Radio National poll, with Trent Dalton’s Boy Swallows Universe taking the top spot. The vote considered books by Australian and overseas authors (fiction and non-fiction), with four of the top 10 and 26 of the top 100 being works written by Australians.

According to the ABC, the poll shows “Australian bookworms love a local writer”. Yet this list lacked the diversity reflecting our country. In particular, it gave little sense of the breadth, creativity and experience of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander writers.

Bruce Pascoe’s Dark Emu was the only Indigenous book to make the top 50 (number 18). Miles Franklin award-winners Carpentaria by Alexis Wright and Too Much Lip by Melissa Lucashenko came in at numbers 82 and 81, respectively.

There is a growing body of First Nations titles being published every year. The massive success of authors such as Wright and Lucashenko – Wright alone has won two Miles Franklin awards and two Stella prizes – signals a long-overdue recognition of First Nations literary excellence.

Given this, here are ten First Nations books from the past 25 years (in no particular order) I would nominate for the books of the century.

1. Terra Nullius by Claire G. Coleman (Hachette, 2017)

When non-Indigenous folks ask for Blak book recommendations, Terra Nullius is almost always my first choice. I can’t tell you much about the actual story because the twist – which comes in the middle rather than the end – is integral to the impact the book will have on readers, but it is one of the most striking works of fiction I have ever read. Coleman has knack for turning a narrative on its head and forcing readers to take stock of their worldview.

2. Heat and Light by Ellen Van Neerven (UQP, 2014)

Ellen van Neerven has an impressive catalogue of works spanning genres and forms. Though it’s difficult to choose just one book from their impressive back catalogue, Heat and Light stands out. While it’s Van Neerven’s debut, there’s something to be celebrated about a first book this mature, elegant and well-crafted. Presented under three thematic motifs, the book (re-released as a First Nations Classic in 2024) is not quite a novel, not quite a short story collection, and defies so-called traditional publishing conventions to span realism, spirituality, connection to Country and futurism.

3. The Yield by Tara June Winch (HarperCollins, 2019)

The Yield is a special work of fiction. Winner of the 2020 Miles Franklin award, this book literally invites readers to take the Wiradjuri language into their mouths – an invitation that feels like a gift when you consider the impacts of colonisation on Aboriginal languages. The story follows Albert “Poppy” Gondiwindi who, dying of pancreatic cancer, has been compiling a dictionary of Wiradjuri words so his knowledge will not be lost. But the language is more than just words on the page – it is connection, Country, culture. It is the taste of words on the tongue, linking to family and history. This is one of those books that benefits from multiple reads as there is always more to discover.

4. Ghost Bird by Lisa Fuller (UQP, 2019)

Like many books in this list, Ghost Bird is one that publishers, reviewers and readers have struggled to “assign” a genre to — a symptom of trying to squeeze cultural writing into narrow marketing categories. This YA book about a sister searching for her missing twin has been described as myth, legend, speculative fiction, magical realism, but it is none of these things. It’s a story that draws from our beliefs, our cultures and the stories that are passed through our families. It’s one of the scariest books I’ve ever read and that’s because I know Fuller’s work is full of truths.

5. That Deadman Dance by Kim Scott (Picador, 2010)

In 2000, Kim Scott became the first Aboriginal person in the prize’s 43 years to win the Miles Franklin literary award with Benang. In 2011, he became the first to receive the award twice with this book, a work of historical fiction set in an 1800s Western Australian community. Scott is a clever storyteller, showing moments where the “first contact” narrative might not have gone the way of colonisation, how things could have turned out differently, but also, importantly, offering hope.

6. The Cherry Picker’s Daughter: A Childhood Memoir by Aunty Kerry Reed-Gilbert (Wild Dingo Press, 2019)

Published in the year of her passing, Aunty Kerry’s memoir is a story of love, community, culture and fierceness. A Wiradjuri elder, Reed-Gilbert tells the story of being raised by her paternal Aunt after her father killed her mother. Despite the difficult subject matter, Aunty writes with love and care for her family and story. As a writer, educator, activist, editor (and more), Aunty Kerry’s impact on Blak writing is immense, with many – like myself – who didn’t have the chance to meet her still benefiting both from reading her incredible body of writing, and the organisations, structures and places she created for us.

7. Harvest Lingo by Lionel Fogarty (Giramondo, 2022)

In his 14th collection of poetry, Lionel Fogarty draws from his work as an activist to examine themes of poverty, class division, politics, history and culture. The writing is challenging and confronting, but this has always been a hallmark of his style. As author Jackie Huggins has noted, Fogarty writes “intentionally” in an Aboriginal way whites can find “alien” and “confusing” that is “digestible, meaningful, accessible and wordly to Aboriginal readers”.

8. Inside My Mother by Ali Cobby Eckermann (Giramondo, 2015)

There is no shortage of talented First Nations poets in this country, but Eckermann, who won the world’s richest literary prize, Yale University’s A$215,000 Windham Campbell prize, in 2017, is one of the best. In this autobiographical collection, she writes through her grief for her birth mother and explores reunion, separation, ritual and connection. Her work is evocative and fierce and she doesn’t shy away from her anger or from gross and terrible things, but at the same time it’s sweet and intimate, as though readers are being invited into some of Eckermann’s most private moments.

9. Took the Children Away by Archie Roach with illustrations by Ruby Hunter (Simon & Schuster, 2010)

If the picture book Where is the Green Sheep by Mem Fox and Judy Horacek can take a place in the ABC’s countdown, then Took the Children Away should definitely be on the list. Adapted from Roach’s very personal song about being taken from his family at two years old, this book revisits the song with illustrations by Ruby Hunter, Roach’s soulmate and musical collaborator. While it doesn’t carry the silliness of The Green Sheep, this book is an important piece of writing that, in picture-book form, can teach young people about the impacts of colonisation and the stolen generations.

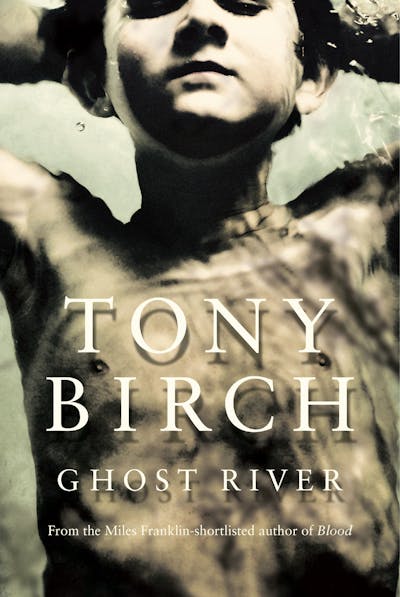

10. Ghost River by Tony Birch (UQP, 2015)

This might prove a surprising choice from Birch’s catalogue of works, which spans fiction and short stories, non-fiction and poetry, but Ghost River is the book that made me fall in love with his writing. Teenage boys seeking freedom and adventure, a daughter raised in a cult, and a group of storytelling vagrants are all brought together by a river that holds secrets and history. This novel explores how difficult childhoods affect adulthood.

If you’re looking to explore the vast history of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander writing from this century and before, searching on AustLit’s BlackWords database offers a great starting point.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Melanie Saward, The University of Queensland

Read more:

- Jamie Oliver wrote First Nations characters the wrong way. Non-Indigenous writers need to listen to Indigenous writers first

- 20 best New Zealand books of the 21st century: as chosen by experts

- 5 First Nations picture books for Australian children to read during NAIDOC week – or any time

Melanie Saward works for the University of Queensland, where the BlackWords database is run. She is an Aboriginal writer, and as such, has connections with many of the authors mentioned in this piece.

The Conversation

The Conversation

Local News in New York

Local News in New York Local News in D.C.

Local News in D.C. America News

America News Raw Story

Raw Story Reuters US Politics

Reuters US Politics Cover Media

Cover Media AlterNet

AlterNet The radio station 99.5 The Apple

The radio station 99.5 The Apple Just Jared

Just Jared