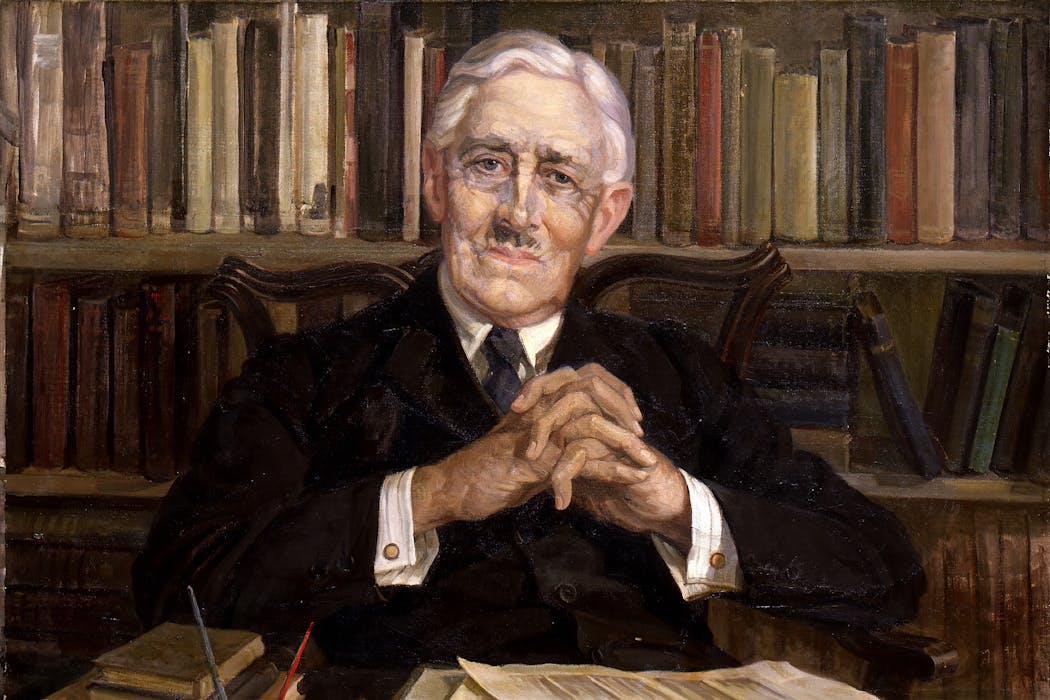

Four days after Plunket founder Sir Truby King’s funeral on February 12 1938, the Auckland Weekly News printed a montage of photographs showing the scale of the event.

Women members of the Plunket Society are shown keeping guard over his coffin. Men and women lined Wellington’s Lambton Quay to see his funeral cortège pass, while others thronged to Mt Melrose to see his casket being borne to the vault at the Karitane Hospital.

Every newspaper in the country noted his death and printed accolades about his service to the nation and the wider world. Prime Minister Michael Joseph Savage described him as a “zealous humanitarian”.

Yet 80 years later, King’s reputation has taken a battering due to his apparent association with now discredited ideas about eugenics. As one 2019 headline put it: “Plunket’s founder was an awful person obsessed with eugenics”.

The article suggested Plunket should apologise for the views of its founder, and has been used as a source for evaluating King in the NCEA level three history curriculum. Separately, I was asked to revise my entry in the Dictionary of New Zealand Biography (I declined).

So the question is, were those New Zealanders who celebrated the life and achievements of Truby King deluded?

The origins of Plunket

Eugenics is commonly used now as a term of opprobrium to describe selective breeding on the basis of “desirable” genetic traits and the weeding out of the “undesirable”.

Originally it simply meant “good in birth”, derived from the Greek eugenes. To understand how the term and the ideas it represents evolved so markedly, and how this applies to Truby King, we need to understand his historical context.

Consider the date he died: February 10 1938. He did not live to see the horror of genocide committed by the Nazi regime which has come to be associated with the term eugenics.

He lived before the establishment of the welfare state by the first Labour government, which instituted free maternity care, state-subsidised doctor’s visits and free hospital care.

There were no antibiotics to miraculously cure infections. There was no readily available and effective contraception.

In 1907, when the Society for the Health of Women and Children was founded (it was renamed the Plunket Society in 1914 after its patron, Lady Victoria Plunket), the infant mortality rate stood at 89 deaths per 1,000 infants. In 2024, the comparable figure was 5.8.

We are far less likely today to experience infant death, whereas in 1907 there was a good chance someone related to us would have.

Plunket offered a free service to urban-based new mothers at a time when doctor’s visits were expensive. Plunket trained Karitane nurses who helped stressed mothers, and provided Karitane Hospitals where they and their babies received care and support.

Women throughout New Zealand joined the organisation and were indefatigable fundraisers to help mothers and save babies.

Early eugenic ideas

If Truby King did think well of some forms of eugenics, he was far from alone. The Otago Daily Times reported that a preliminary meeting of the proposed Dunedin branch of the Eugenics Education Society drew “a large number of medical and university men, ministers, headmasters of schools [and] philanthropic workers…”.

Truby King’s name does not appear in the list of officers or members of the Eugenics Education Society council. But while his name is also absent from any reports in its first year, the society was pleased to receive a letter from Āpirana Ngata, cofounder of the Young Māori Party and MP for Eastern Māori.

Ngata wrote that the party believed its own policies would be enhanced by “scientific principles, based on practical research” which he evidently believed to be the aim of the society.

In May 1911, the Society for the Health of Women and Children invited distinguished University of Otago professor William Benham to address its annual meeting.

Benham had recently become president of the Eugenics Education Society and used his platform to insist that “heredity is more important than environment”, and that if the right people didn’t reproduce, the “race” would deteriorate.

Truby King was quick to repudiate this argument and emphasise the importance of environment. If the public were led to believe heredity counted for everything and the environment for nothing, he suggested, it would lead to “masterly inactivity”.

By this he meant that while you could not alter an individual’s heredity, you could control the environment into which they were born. The best thing was to make that environment conducive to good health for every baby.

In the book Eugenics at the Edges of Empire, historian Diane Paul discusses how we can trace King’s concern about the differential birthrate between the “fit” and the “unfit”, and the “best sources” of population, in his speeches and written works.

But he did not regard “unfitness” as an unalterable trait. Rather, with the best start in life, all children would become “fit”. And there is no evidence he ever joined the Eugenics Education Society.

The past in context

Eugenic theories have to be viewed through the lens of history. It might help to think of these ideas in the early 20th century as being like water – flowing everywhere and adopted for different uses by different constituencies.

It would have been hard not to be caught in the tide of what was then thought of as a frontier of scientific knowledge. But Truby King was determined to swim against the tide of indifference to the social conditions he feared might be the result of an emphasis on heredity.

He wanted action to improve outcomes for infants and mothers. And those New Zealanders who lined the streets to mark his death believed he had succeeded.

Science, of course, advances. And there have been dramatic improvements in the understanding of genetics. These days, Te Whatu Ora-Health New Zealand offers fully funded prenatal screening to determine the risk of the fetus having certain chromosomal abnormalities, in order to allow women to make their own decisions about continuing a pregnancy.

To describe this as “eugenics”, a word now freighted with the horrors of Nazi state policy, would no doubt cause an outcry from those who have benefited from such screening.

In the contemporary condemnation of Truby King, I think we can see a failure of historical imagination of the kind prominent British historian E.P. Thomson called the “enormous condescension of posterity”.

Diane Paul suggests the term “eugenics” had such a wide compass in King’s era that it does no useful analytical work, but has become merely an emotive term.

One of New Zealand’s early women doctors, Frances Preston, once related the story of when Truby King, as Inspector of Asylums, paid a visit to the Seacliff Lunatic Asylum. He was given rooms near the entrance for his overnight stay. A conscientious night watchman noticed a sleeping man and locked the door.

When he found himself imprisoned in the morning, a furious King cried “Let me out, Let me out! I’m Sir Truby King.” The morning attendant assumed this was the raving of a patient and replied soothingly, “Yes, yes, we’ve got two more Sir Trubys upstairs.”

Just like the attendant who failed to recognise Truby King, it seems current criticism fails to discern the extremely broad meaning of the term eugenics a century ago, and King’s genuine motivations in founding what became Plunket.

New ideas about raising children, and the cushion of free hospital and maternity care, have made his ideas seem outdated. But we should not uncritically associate him (or besmirch his reputation) with a term that has come to stand for something else, the most extreme and appalling applications of which took place after his time.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Barbara Brookes, University of Otago

Read more:

- Progressive eugenics is hardly history – the science and politics have just evolved

- How Trump’s racist talk of immigrant ‘bad genes’ echoes some of the last century’s darkest ideas about eugenics

- Uninformed comments on autism are resonant of dangerous ideas about eugenics

Barbara Brookes does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The Conversation

The Conversation

America News

America News CBS News

CBS News Ars Technica Science

Ars Technica Science The Daily Beast

The Daily Beast Akron Beacon Journal Sports

Akron Beacon Journal Sports CNN

CNN RadarOnline

RadarOnline PBS NewsHour Politics

PBS NewsHour Politics Raw Story

Raw Story