You might think of Australia’s arid centre as a dry desert landscape devoid of aquatic life. But it’s actually dotted with thousands of rock holes – natural rainwater reservoirs that act as little oases for tiny freshwater animals and plants when they hold water.

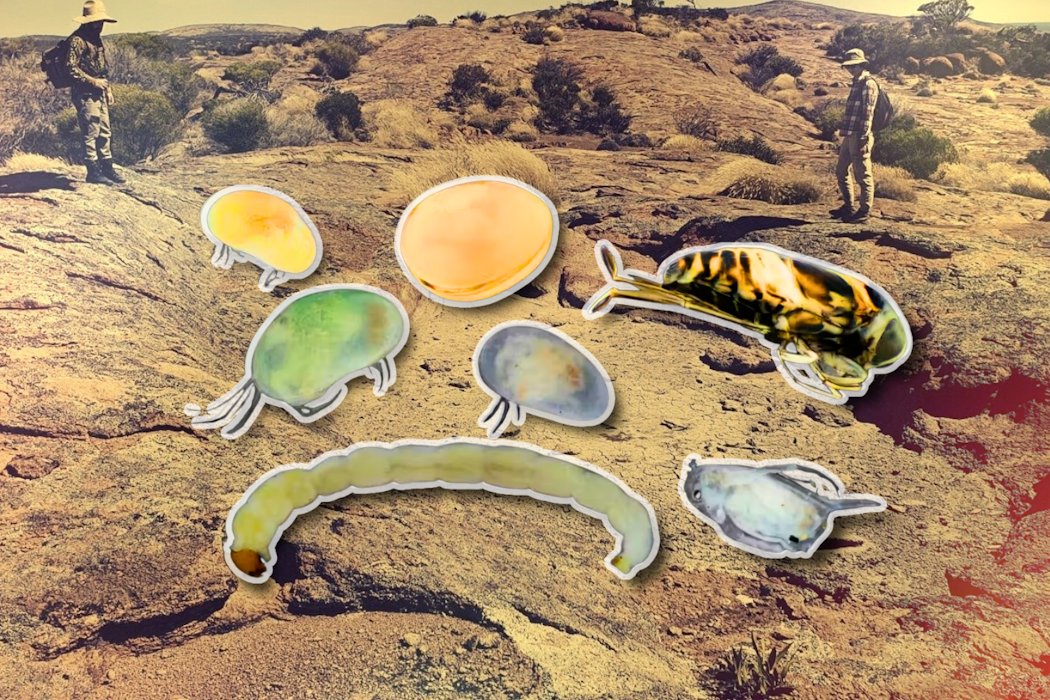

They aren’t teeming with fish, but are home to all sorts of weird and wonderful invertebrates, important to both First Nations peoples and desert animals. Predatory damselflies patrol the water in search of prey, while alien-like water fleas and seed shrimp float about feeding on algae.

Often overlooked in favour of more photogenic creatures, invertebrates make up more than 97% of all animal species, and are immensely important to the environment.

Our new research reveals 60 unique species live in Australia’s arid rock holes. We will need more knowledge to protect them in a warming climate.

Overlooked, but extraordinary

Invertebrates are animals without backbones. They include many different and beautiful organisms, such as butterflies, beetles, worms and spiders (though perhaps beauty is in the eye of the beholder!).

These creatures provide many benefits to Australian ecosystems (and people): pollinating plants, recycling nutrients in the soil, and acting as a food source for other animals. Yet despite their significance, invertebrates are usually forgotten in public discussions about climate change.

Freshwater invertebrates in arid Australia are rarely the focus of research, let alone media coverage. This is due to a combination of taxonomic bias, where better-known “charismatic” species are over-represented in scientific studies, and the commonly held misconception that dry deserts are less affected by climate change.

Oases of life

Arid rock-holes are small depressions that have been eroded into rock over time. They completely dry out during certain times of year, making them difficult environments to live in. But when rain fills them up, many animals rely on them for water.

When it is hot, water presence is brief, sometimes for only a few days. But during cooler months, they can remain wet for a few months. Eggs that have been lying dormant in the sediments hatch. Other invertebrates (particularly those with wings) seek them out, sometimes across very long distances. In the past, this variability has made ecological research extremely difficult.

Our new research explored the biodiversity in seven freshwater rock holes in South Australia’s Gawler Ranges. For the first time, we used environmental DNA techniques on water samples from these pools.

Similar to forensic DNA, environmental DNA refers to the traces of DNA left behind by animals in the environment. By sweeping an area for eDNA, we minimise disturbance to species, avoid having to collect the animals themselves, and get a clear snapshot of what is – or was – in an ecosystem. We assume that the capture window for eDNA goes back roughly two weeks.

These samples showed that not only were these isolated rock holes full of invertebrate life, but each individual rock hole had a unique combination of animals in it. These include tiny animals such as seed shrimp, water fleas, water boatman and midge larvae. Due to how dry the surrounding landscape is, these oases are often the only habitats where creatures like these can be seen.

Culturally significant

These arid rock holes are of great cultural significance to several Australian First Nations groups, including the Barngarla, Kokatha and Wirangu peoples. These are the three people and language groups in the Gawler Ranges Aboriginal Corporation, who hold native title in the region and actively manage the rock holes using traditional practices.

As reliable sources of freshwater in otherwise very dry landscapes, these locations provided valuable drinking water and resting places to many cultural groups. Some of the managed rock holes hold up to 500 litres of water, but elsewhere they are even deeper.

Diverse practices were traditionally developed to actively manage rock holes and reliably locate them. Some of these practices — such as regular cleaning and limiting access by animals — are still maintained today.

Threatened by climate change

Last year, Earth reached 1.5°C of warming above pre-industrial levels for the first time. Australia has seen the dramatic consequences of global climate change firsthand: increasingly deadly, costly and devastating bushfires, heatwaves, droughts and floods.

Climate change means less frequent and more unpredictable rainfall for Australia. There has been considerable discussion of what this means for Australia’s rivers, lakes and people. But smaller water sources, including rock holes in Australia’s deserts, don’t get much attention.

Australia is already seeing a shift: winter rainfall is becoming less reliable, and summer storms are more unpredictable. Water dries out quickly in the summer heat, so wildlife adapted to using rock holes will increasingly have to go without.

Drying out?

Climate change threatens the precious diversity supported by rock holes. Less rainfall and higher temperatures in southern and central Australia mean we expect they will fill less, dry more quickly, and might be empty during months when they were historically full.

This compounds the ongoing environmental change throughout arid Australia. Compared with iconic invasive species such as feral horses in Kosciuszko National Park, invasive species in arid Australia are overlooked. These include feral goats, camels and agricultural animal species that affect water quality. Foreign plants can invade freshwater systems.

Deeper understanding

Many gaps in our knowledge remain, despite the clear need to protect these unique invertebrates as their homes get drier. Without a deeper understanding of rock-hole biodiversity, governments and land managers are left without the right information to prevent further species loss.

Studies like this one are an important first step because they establish a baseline on freshwater biodiversity in desert rock holes. With a greater understanding of the unique animals that live in these remote habitats, we will be better equipped to conserve them.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Brock A. Hedges, University of Adelaide; James B. Dorey, University of Wollongong, and Perry G. Beasley-Hall, University of Adelaide

Read more:

- From the Miller’s Tale to King Lear’s roaring sea, a history of flooding in literature

- Sumatra’s flood crisis: How deforestation turned a cyclonic storm into a likely recurring tragedy

- Will the government’s new gas reservation plan bring down prices? Yes, if it works properly

Brock A. Hedges received funding from Nature Foundation, The Ecological Society of Australia and the Department of Agriculture, Water and Environment. Brock A. Hedges currently receives funding from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

James B. Dorey receives funding from the University of Wollongong.

Perry G. Beasley-Hall receives funding from the Australian Biological Resources Study.

The Conversation

The Conversation

The Gazette

The Gazette Click2Houston

Click2Houston Ocala Star-Banner

Ocala Star-Banner The Daily Beast

The Daily Beast America News

America News The Hollywood Gossip

The Hollywood Gossip Raw Story

Raw Story Associated Press US News

Associated Press US News