In recent decades, the number and severity of wildfires across Canada has increased due to climate change and a more wildfire-prone landscape.

While wildfires can wreak havoc in their immediate area, wildfire smoke can travel thousands of kilometres, putting millions more people at risk from the adverse impacts.

Research on wildfire smoke and health shows that smoke is more than just an irritant. It is increasingly clear that older adults, pregnant people and young children face higher risks to their health, including premature birth, hospitalization and premature death.

One way to reduce smoke exposure is to stay indoors and create a “clean air shelter” by closing the doors, windows and using an air cleaner to remove smoke and other particles from the air.

However, that is easier said than done for many people. While effective, store-bought air cleaners can be expensive and require pricey replacement filters.

In addition, many homes don’t have air conditioners and easily trap heat. Closing all windows means reducing ventilation, and can make hot summer days even more unpleasant. Another option, popularized during the COVID-19 pandemic, is the idea of building your own air cleaner, using easily sourced parts from local hardware stores.

Do-it-yourself air cleaners

In British Columbia, we started The BREATHE Project to study the impacts of wildfires and distribute information about DIY air cleaners.

A 2023 article by the National Collaborating Centre for Environmental Health compiled evidence on the effectiveness of do-it-yourself (DIY) air cleaners as an alternative to store-bought units.

The results showed that DIY air cleaners are not only more affordable and accessible, but are equally as effective, as long as the correct parts are used and the room size is taken into consideration.

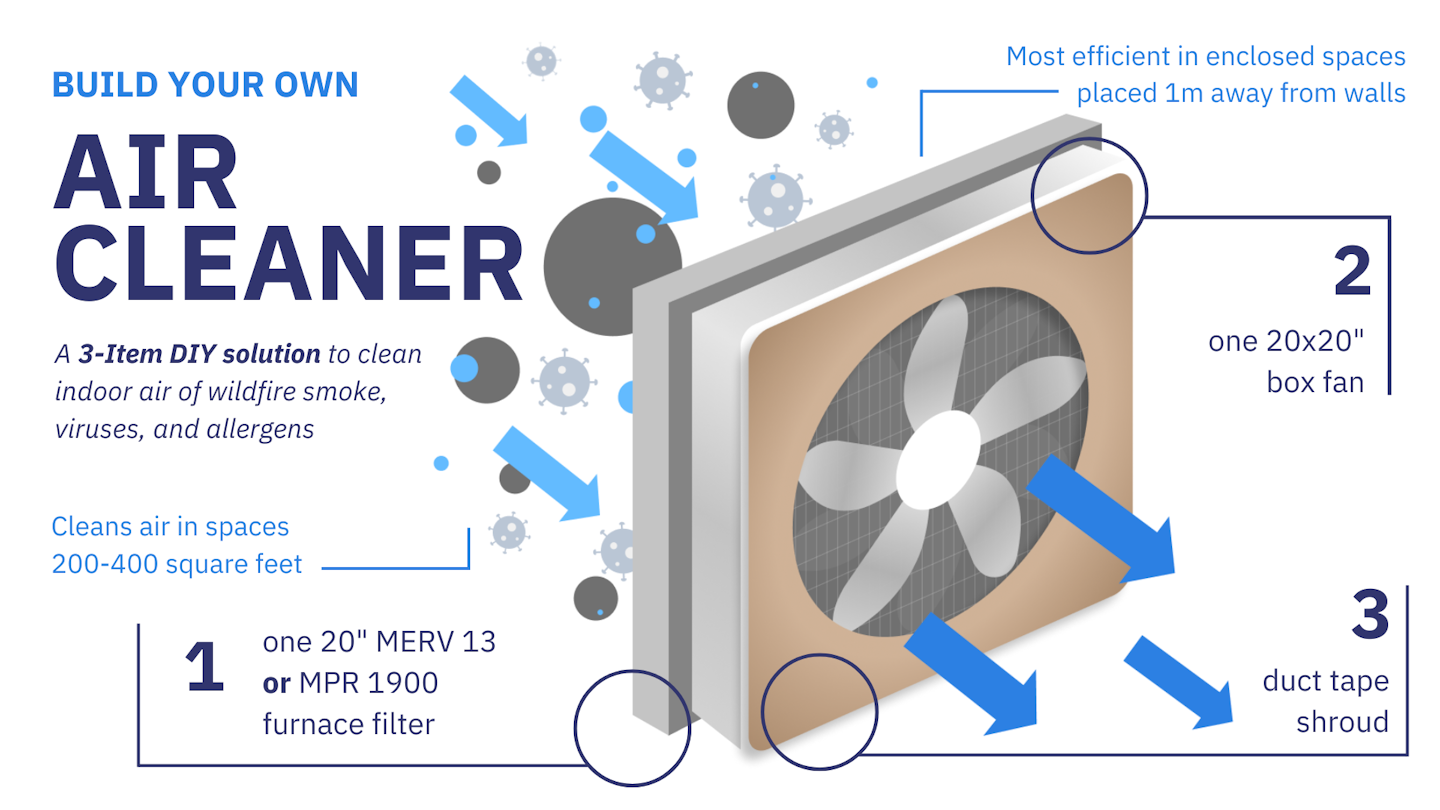

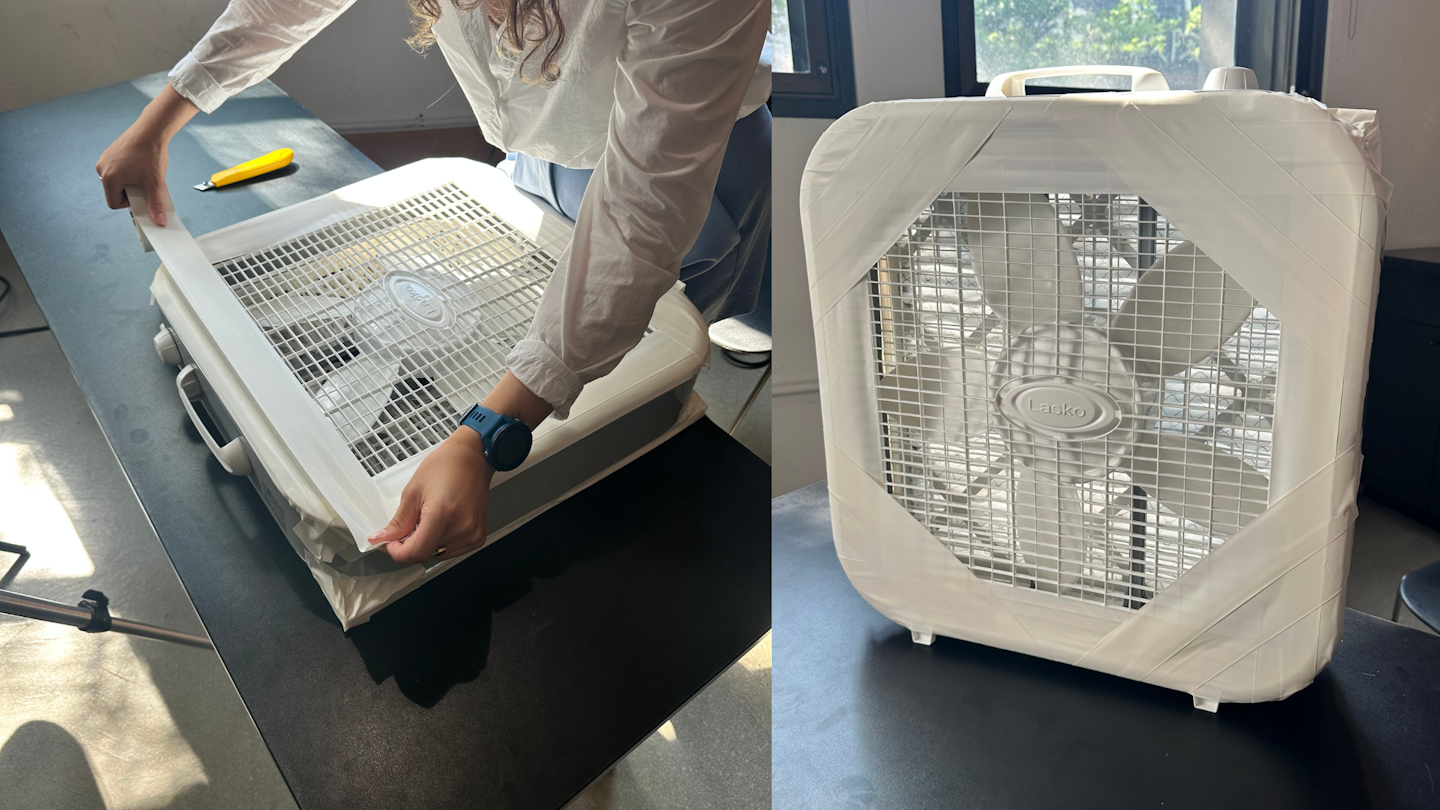

This includes the use of a MERV-13 filter, a minimum 75-watt box fan, duct tape and a shroud cover on the front corners of the fan. One unit can clean a small room, and multiple units can be used for larger spaces.

DIY air cleaners also help reduce other air contaminants including allergens, mold spores, emissions from woodstoves, respiratory pathogens, dust, and traffic related air pollutants.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency found similar results in their analysis of DIY air cleaners and determined that the units are safe to use as built.

The BREATHE Project

Our team at Simon Fraser University partnered with the BC Lung Foundation to share this knowledge about cleaner indoor air with communities across British Columbia.

In 2023, we launched a pilot project in the Lower Mainland to find out if workshops about making DIY air cleaners could be feasible. These workshops were held in community centers, libraries, seniors’ centers and neighbourhood houses, with the average participant being over 70 years old and with at least one medical condition.

We were surprised to find that our workshops were fully booked within days of advertising, and that news of our project was quickly spreading by word of mouth within communities.

We used participant feedback to fine-tune our materials and created instructional videos, and a train-the-trainer manual to guide other organizations on how to host similar workshops.

In 2024, we took the project into B.C.’s Interior Health Authority region, where fires were more frequent and more severe.

We named our project BREATHE: Building Resilience to Emerging Airborne Threats and Heat Events and have since added additional resources for communities grappling with the co-exposure of wildfire smoke and extreme heat.

BREATHE has now partnered with all of B.C.’s health authorities. We have hosted over 90 workshops so far this year, many in northern, rural and remote regions. Workshops have been held in the Cowichan Valley, Lower Mainland, Central Okanagan, the Kootenays and the Northern Rockies.

The project has helped build over 2,500 air cleaners and brought important information about community resilience to people directly impacted by these exposures.

BREATHE also serves as a launchpad for research on the impacts of wildfire smoke on at-risk populations across the province.

Everyone can take steps to protect their health when it is smoky outside. Our resources, including our train-the-Trainer guides and step-by-step videos are free and available on our website. If you are interested in hosting your own workshops, or seeking a collaboration, please reach out through our website.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Anne-Marie Nicol, Simon Fraser University and Prem Gundarah, Simon Fraser University

Read more:

- Is that wildfire smoke plume hazardous? New satellite tech can map smoke plumes in 3D for better air quality alerts at neighborhood scale

- Wildfire smoke and extreme heat can occur together: Preparing for the combined health effects of a hot, smoky future

- Dealing with wildfires requires a whole-of-society approach

Anne-Marie Nicol is a Knowledge Mobilization Specialist at the BC Centre for Disease Control.

Prem Gundarah does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The Conversation

The Conversation

KSL Utah

KSL Utah The Grand Rapids Press

The Grand Rapids Press KQED Politics

KQED Politics KTNV Channel 13 Las Vegas

KTNV Channel 13 Las Vegas The Hard Times

The Hard Times Lynnwood Today

Lynnwood Today The Columbian Business

The Columbian Business ABC News Video

ABC News Video The Hill

The Hill