After the Great War, Australians made pilgrimages to distant battlefields of Gallipoli and northern France. They paid their respects to the fallen soldiers who shaped our national identity.

After the second world war, new places emerged such as the Kokoda Track, Papua New Guinea; Changi, Singapore; and the Thai-Burma railway. They became synonymous with Australia’s wartime sacrifices in Asia and the Pacific.

However, few know about Yokohama War Cemetery – the only Commonwealth war cemetery in mainland Japan. This unique site was collaboratively designed and built by Australian and Japanese architects, horticulturists and contractors in the years following the war.

It marks one of the first acts of reconciliation between the two nations after hostilities ceased.

Reimagining the cemetery

Yokohama War Cemetery was established as the final resting place for more than 1,500 Allied servicemen and women. Most had died as prisoners of war in Japan and China, including 280 Australians.

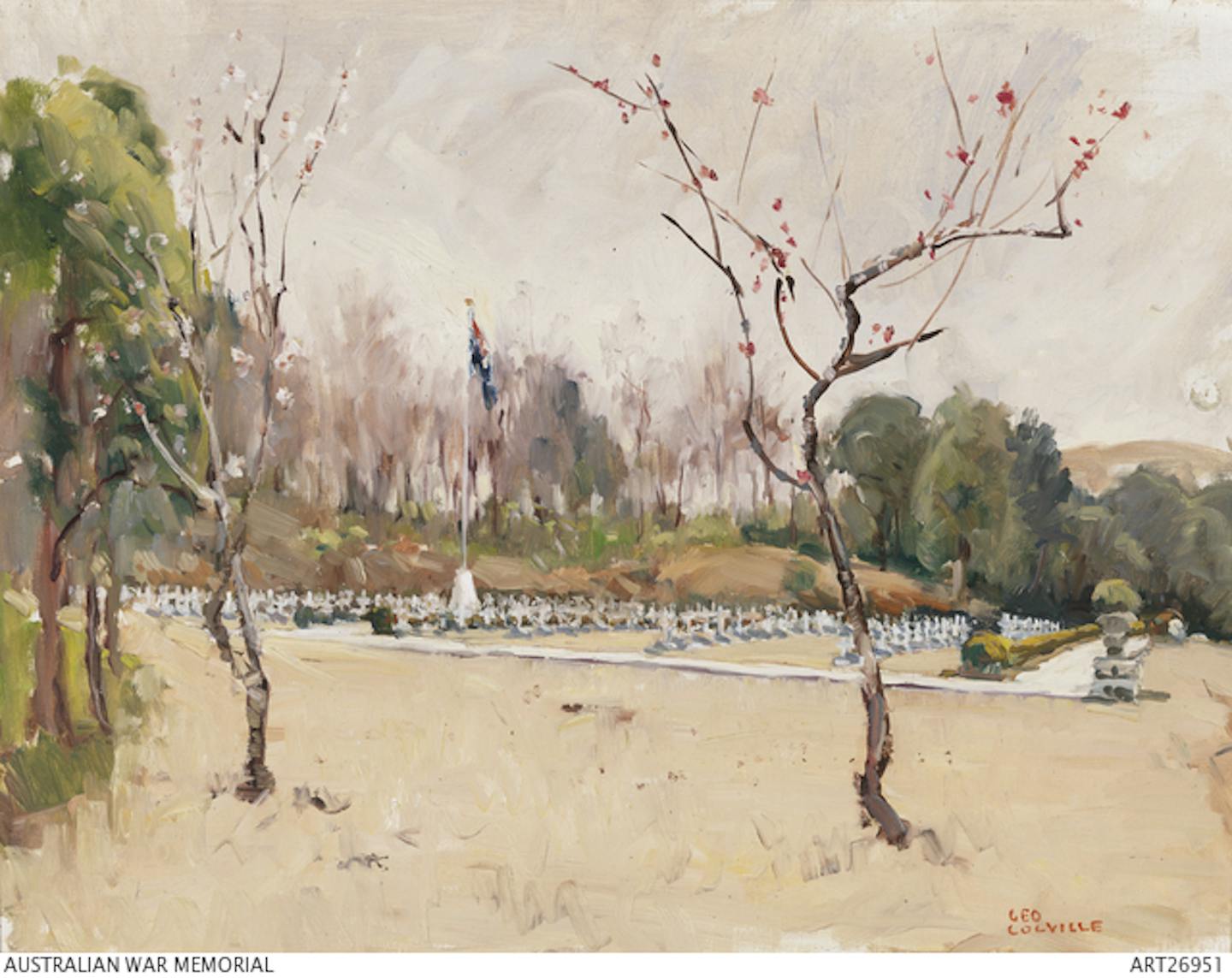

About six kilometres west of Yokohama’s historic port, the cemetery sits within a thick pine and cherry tree landscape. After the war ended, Australian and American war graves teams scoured Japan to locate and identify the remains of the fallen. They were often found in the care of local temples near prisoner-of-war camps.

Between 1946 and 1951, a small team of Australian architects and horticulturists designed and constructed the cemetery. They were from the Melbourne-based Anzac Agency of the Imperial War Graves Commission (now known as the Office of Australian War Graves).

Many of these designers were recently returned servicemen.

They include young architects Peter Spier, Robert Coxhead, Brett Finney and Clayton Vize. All trained at the University of Melbourne’s Architectural Atelier, their fledgling careers interrupted by years of war service and at the agency. Others, such as Alan Robertson, endured years as a prisoner of war in Singapore then Japan.

These architects reimagined the flat expanse of the traditional British war cemetery. They arranged a 27-acre former children’s amusement park into five national burial grounds: for the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand–Canada, pre-Partition India, and a post-war section.

Eucalyptus trees towering above the mature foliage clearly identify the cemetery as an Australian endeavour.

Another important contributor was Alec Maisey, a former merchant seaman and New Guinea veteran. Maisey took on the horticultural duties for the Anzac Agency’s numerous war cemeteries. In New Guinea, Borneo, Indonesia, New Caledonia, the South Pacific and across mainland Australia, he left behind a lasting landscape legacy for the thousands of visitors.

An international collaboration

Australian designers collaborated with their Japanese counterparts to create a memorial landscape. They embedded the commission’s established lawn cemetery template into a Japanese style “hide and reveal” garden that conceals and reveals the view as you walk through it.

Impressed by Frank Lloyd Wright’s use of native Oya stone at the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo, modernist architect Yoji Kasajima introduced it at the cemetery.

Japanese-American Michael Iwanaga was the principal local architect for the cemetery and introduced the Australians to the social and cultural norms of Japanese funerary architecture.

The main contractor on the project, Yabashi Marble, was associated with Japan’s modernist architecture renaissance. They installed the interior stone for Japan’s parliament building.

Tokio Nursery was initially an importer and exporter of seeds, bulbs and plants. They turned to landscaping after the war, becoming the cemetery’s principal gardening and maintenance contractor.

These tentative first steps towards reconciliation between Australia and Japan were made through design.

The result was a war cemetery unique to Asia, combining Asian and Western funereal features and aesthetics in its design.

Through these encounters, the Australian designers’ gained a deeper understanding of Japan’s materials, flora and landscape. Working closely with Japanese architects, nurseries and contractors, their approach to and perception of their profession and Japan was transformed.

Among many cemeteries they designed throughout Asia, Yokohama was the place they often returned to and drew inspiration from in their personal lives.

Enduring reminders

War does not end with a victory or a battle. Some of the most difficult tasks are carried out by the seemingly obscure units of the Australian army. The Australian war graves services, undertook the recovery of the war dead, providing for their dignified burial in designated cemeteries.

Many of these spaces were designed and created during the last stages of the conflict.

War cemeteries are often activated only during commemorative anniversaries. Yet, they persist in serving as enduring reminders of the futility of war and the scale of a nation’s sacrifice. They trigger intergenerational memories for Australians.

For many Asians, however, these sites often represent an unwelcome age of imperial conflicts in which their service and sacrifice was often overlooked.

Yokohama War Cemetery stands as a testament to the collaborative efforts of Australian and Japanese designers in the aftermath of the second world war. It offers a unique perspective on the journey towards reconciliation and the power of design to bridge cultural divides.

The exhibition Eucalypts of Hodogaya is at the Shrine of Remembrance, Melbourne, until August 2026.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Anoma Darshani Pieris, The University of Melbourne and Athanasios Tsakonas, The University of Melbourne

Read more:

- Postwar Japan at 80: 10 factors that changed the nation forever

- Ancient Incans of all classes used coded strings of hair for record keeping – new research

- How a Japanese museum project is passing on the testimony of the last atomic bomb survivors

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The Conversation

The Conversation

Newsweek Top

Newsweek Top Local News in D.C.

Local News in D.C. AlterNet

AlterNet Reuters US Top

Reuters US Top Rolling Stone

Rolling Stone Reuters US Domestic

Reuters US Domestic KUOW Public Radio

KUOW Public Radio Wyoming Tribune Eagle

Wyoming Tribune Eagle NBC 7 San Diego Sports

NBC 7 San Diego Sports