From Melbourne’s proposed Outer Metropolitan Ring Road to Sydney’s recently completed Westconnex, Australia’s addiction to mega roads continues despite the spectre of climate change.

The stream of projects shows Australia’s approach to urban transport is stuck in the car-obsessed past. It’s an approach at odds with state planning policies that prioritise other less-polluting transport modes, such as train and tram extensions, bike lane infrastructure and better pedestrian footpaths.

As the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has warned, roads hinder national efforts to meet climate targets. They “lock in” emissions, by establishing long-term infrastructure that commits societies to greenhouse gas emissions for decades to come.

Expanding freeway networks undermines efforts to reduce emissions and encourage cleaner transport. It points to a deep-seated flaw in Australia’s urban planning systems which must be solved.

No road to net zero

Australia has committed to reach net zero greenhouse emissions by 2050.

Meeting the goal requires, among other measures, dealing with greenhouse gas emissions from transport – which is set to become the nation’s largest source of emissions by 2030.

Globally, roads account for 69% of transport emissions, and this is growing.

Despite this, a number of mega roads are planned or being built in Australian cities. They include:

- Sydney’s M12 Motorway

- Brisbane’s Gateway Motorway and Bruce Highway upgrades

- Adelaide’s River Torrens to Darlington Project

- Perth’s Tonkin Highway Extension and Thomas Road Upgrade

- Melbourne’s Outer Metropolitan Ring Road.

Here, we examine the Melbourne project in more detail.

Melbourne’s mega ring road

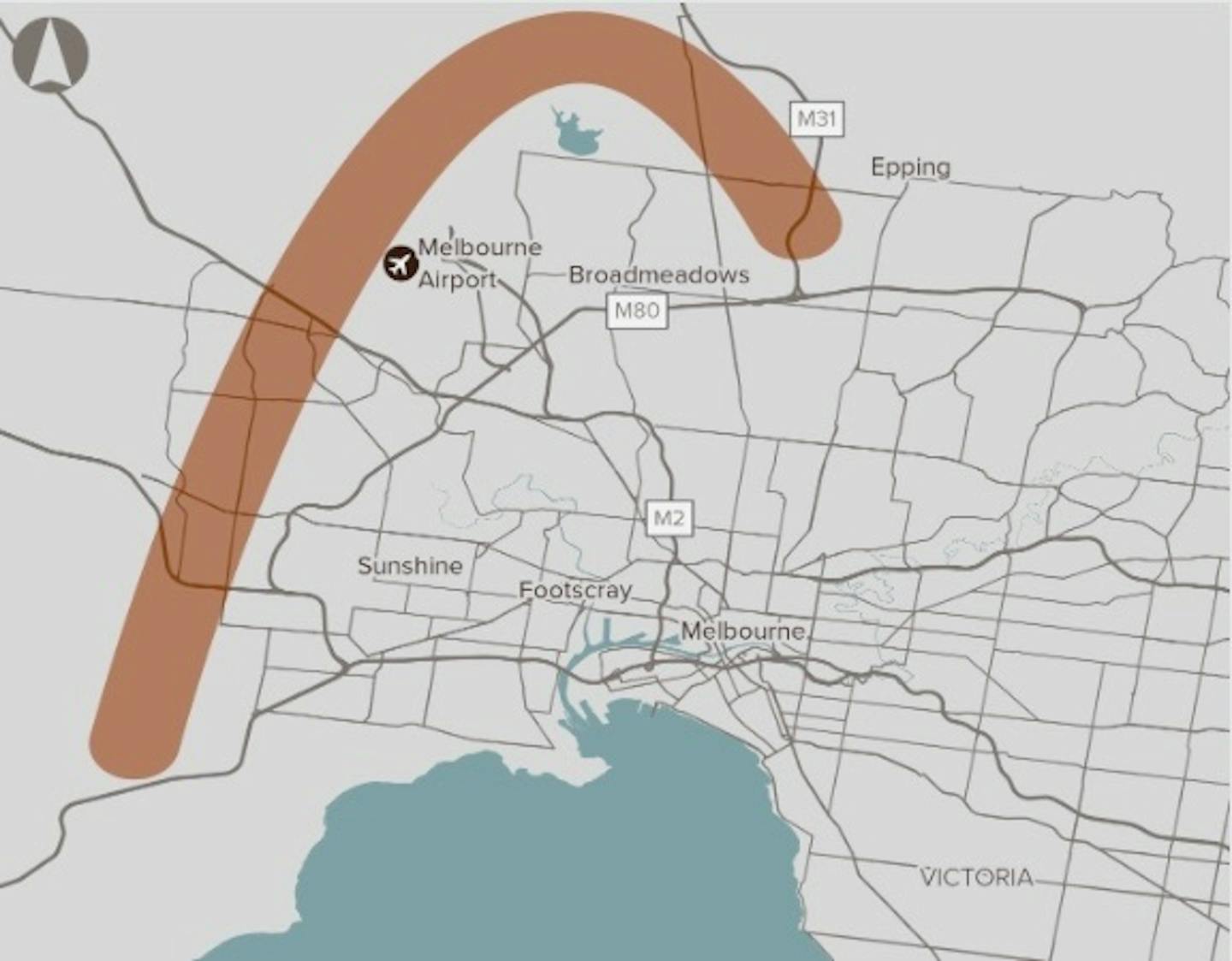

The Outer Metropolitan Ring Road would involve a 100-kilometre freeway orbiting Melbourne’s north and west. With a current price tag of A$31 billion, it would be among the most expensive road projects in an Australian city.

In 2009, the Brumby Labor government in Victoria deemed the project could proceed without an “environmental effects statement” – including assessment of it climate impacts.

Rationales for the decision included that the project passes through land extensively disturbed in the past, and because sustainability implications had been considered in overarching state planning blueprints.

It is unclear whether, given the time that has lapsed, whether the project will be reconsidered for environmental approval – and if so, what level of scrutiny would be applied.

Given the project’s potential contribution to transport emissions, authorities should reverse the exemption and ensure it is subject to the highest environmental scrutiny. This is vital to ensure the public is fully aware of – and can object to – the project’s climate impacts.

Our research has previously identified such issues involving public consultation and major road projects. They include Melbourne’s East West Link and West Gate Tunnel, and Sydney’s Westconnex . In the case of Westconnex, the “public interest” was narrowly defined and inadequate in addressing climate change concerns.

A 2017 Victorian Auditor-General Report also found a power imbalance between project proponents and community participants. For instance, proponents usually had legal representation while community members did not.

What’s more, emissions reduction must be central to the policies governing Australia’s built environments, as we discuss below.

Climate must be key

Residents in Australia’s capital cities are largely car-dependent. More climate-friendly transport modes, such as walking and cycling, can be difficult due to long distances between destinations, and lack of supporting infrastructure such as bike paths.

The IPCC recommends minimising emissions generated in cities through:

- infill development (building on unused land in urban areas)

- increasing density (the number of people living in a certain area)

- improving public transport

- supporting walking, cycling and other “active” transport options.

State planning blueprints in Australia typically consider land use and transport together. Victoria, for example, wants more homes built in established areas, close to public transport, services and jobs. Transport plans in states such as NSW and Queensland have similar goals.

However, the need for climate action and emissions reduction is typically not fully integrated across these policies. And federal government guidelines on transport planning also give little regard to net zero targets.

This means major road projects can proceed without direct consideration of emissions reduction and net zero goals.

A different road

Urban planning policies are not the only government levers available to reduce vehicle emissions.

The federal government’s fuel efficiency standards, for example, began in January this year. But some experts say the policy – which is weaker than that initially proposed – does not go far enough to cut transport emissions.

Separately, the National Electric Vehicle Strategy is a positive step. But Australia is badly lagging in EV uptake, and much more work is needed.

As Australian cities continue to grow, the demand for travel will also increase. But new freeway projects are not the answer – they will only make climate change worse.

Reform is needed to ensure emissions reduction is at the heart of transport investment in our cities.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Crystal Legacy, The University of Melbourne; Anna Hurlimann, The University of Melbourne, and Eric Keys, RMIT University

Read more:

- The canary in the concrete jungle: how polluted towns make sparrows frail, anxious and old before their time

- How a global plastic treaty could cut down pollution – if the world can agree one

- Climate models reveal how human activity may be locking the Southwest into permanent drought

Crystal Legacy receives funding from the Australian Research Council to support her research on infrastructure planning, public participation and the future of urban transport governance. She has also previously received research from the Henry Halloran Trust and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (Canada).

Anna Hurlimann received funding from the Australian Research Council Discovery Grant for research on climate change action in cities. She is a member of the Planning Institute of Australia.

Eric Keys is affiliated with the Victorian Transport Action Group.

The Conversation

The Conversation

Local News in Florida

Local News in Florida Orlando Sentinel

Orlando Sentinel The Grand Rapids Press

The Grand Rapids Press Spectrum News Louisville

Spectrum News Louisville Arizona Daily Sun

Arizona Daily Sun Reno Gazette-Journal

Reno Gazette-Journal Mesa Independent

Mesa Independent Edmonton Sun World

Edmonton Sun World Raw Story

Raw Story