The power of the war photograph is that it won’t let you look away. And nowhere is this proving truer than in Gaza.

One recent example portrayed a skeletal boy, Muhammad Zakariya Ayyoub al-Matouq, held in his mother’s arms. Palestinian photographer Ahmed al-Arini captured the boy and his mother in the iconic pose of the Madonna and child.

Photographs coming out of Gaza since October 2023 have communicated the severity of the destruction: collapsed buildings, bodies in shrouds, dead and maimed children, and bombed-out hospitals and shelters. There have also been viral AI-generated images, such as All Eyes on Rafah.

But none of these galvanised the public as much as the photographic evidence of Israel’s systemic starvation of Gazans. These photos were ubiquitous among the tens of thousands who marched across the Sydney Harbour Bridge on August 3.

Between April and July, more than 20,000 people in Gaza were hospitalised for malnutrition, including 3,000 children in life-threatening condition.

The photo of Muhammad is a visual condensation of collective suffering that is impossible to ignore or deny. This is what makes it so powerful.

Drawing from religious imagery

War photography is often impactful because it communicates the brutalities of war with visual mastery.

Photographic elements such as composition, timing, tone, colour and light combine to create a visual story that is full of intent.

This is what American photographer and curator John Szarkowski called “the photographer’s eye”, and what French photographer Henri Cartier Bresson coined as “the decisive moment”. It is to know where to point the camera, when to release the shutter and how to select the “right” image to release into the world.

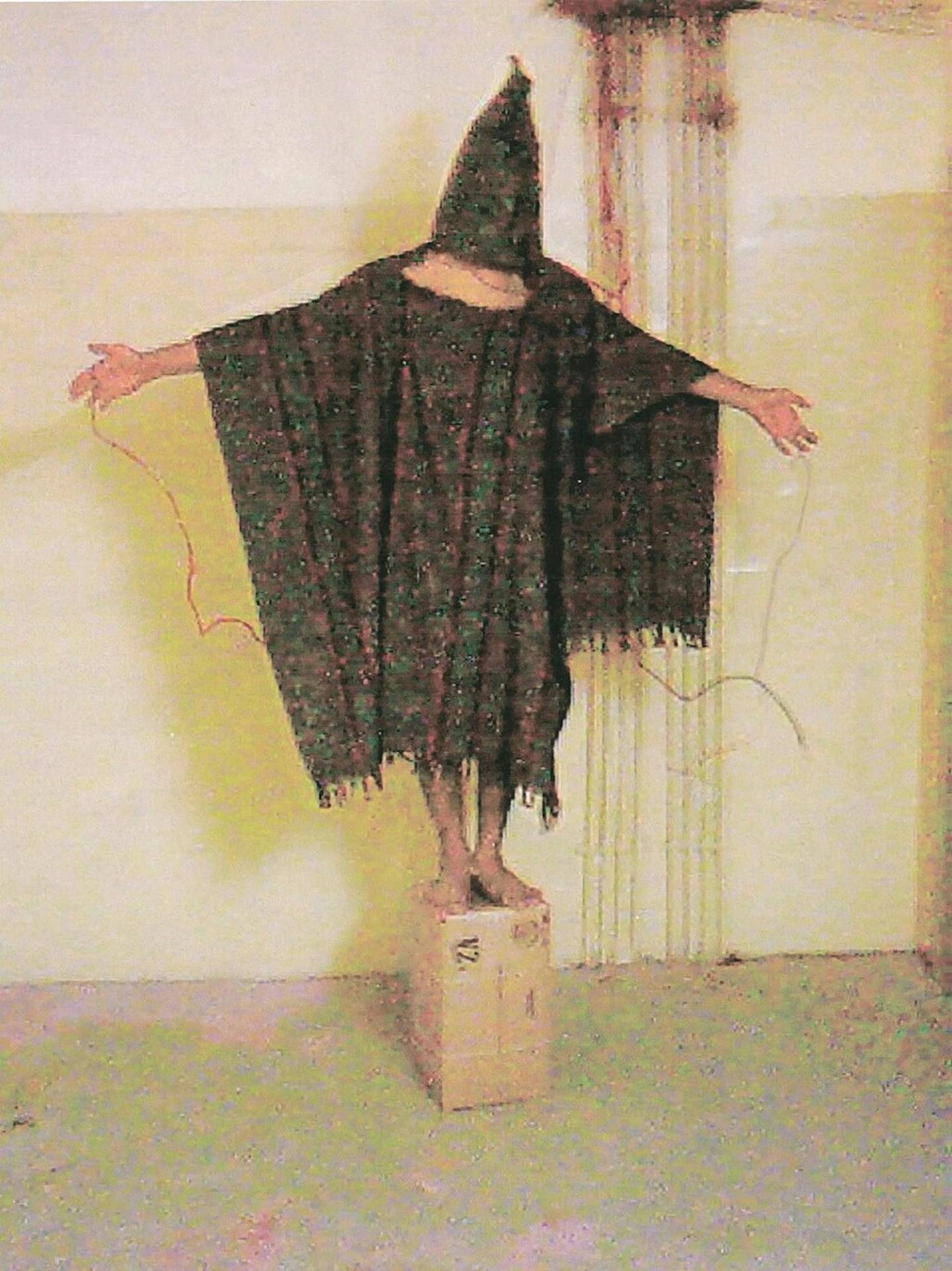

An iconic war photograph often reproduces a pose or gesture that is familiar to the popular imagination – particularly through iconic religious imagery. Think of the horrifying photos that came out of Abu Ghraib prison during the Iraq War, where one tortured prisoner was photographed in the pose of Christ on the cross.

This was equally true of the 1972 image of Phan Thi Kim Phúc, the naked girl fleeing napalm in Vietnam with her arms outstretched.

Such photographs can change the course of war. They often shape how wars are remembered, even when there is controversy around their truthfulness and authorship, as we have seen with the contested image of Kim Phúc.

Truthfulness and authorship

Historically, there have been many controversies over the staging of war photographs. Robert Capa’s Falling Soldier (Loyalist Militiaman at the Moment of Death, Cerro Muriano, September 5, 1936) is one of the most famous and yet disputed images in the history of war photography.

It purports to show a soldier shot dead mid-fall during the Spanish Civil War. But historians suggest the man might have been posing, not dying.

Whether it is real or staged remains unresolved. Still, it circulates as though it is true – reminding us that the myths of war are just as important as the facts when it comes to how war is remembered.

Photos are limited by their inability to convey sound, smell, or any broader context. A staged photo might, at times, be even more effective than an unstaged one in conveying the lived experience of a war – even if the ethics of the staging are dubious.

The weaponisation of war imagery

Photos and video from Gaza continue to circulate on social media, despite Israel barring foreign journalists from entering Gaza.

Israeli authorities have killed Palestinian journalists in record numbers. Yet this visual censorship has not stopped citizen journalists and organisations such as Activestills from sharing the atrocities in Gaza.

In Gaza, control over imagery has become part of the conflict. Al Jazeera was banned from operating inside Israel. Social media platform Meta has been found silencing posts from Palestinian accounts, with graphic images increasingly being labelled with warnings such as “sensitive content”.

What does it mean to be advised to look away from something someone else is living?

Read more: Social media platforms are complicit in censoring Palestinian voices

As we know from the second world war, images are powerful evidence. The photographs of starved concentration camp survivors during the Holocaust were used to prosecute Nazis at the Nuremberg Trials.

But the meaning of war photographs also depends on timing, context, who controls what is shown, and where the photos are distributed.

While these photos can communicate the horrors of a conflict, they are also entangled in acts of violence. In Abu Ghraib, American soldiers used photography to turn their war crimes into visual souvenirs. Similarly, Al Jazeera is collecting such “trophies” shared by Israeli soldiers as evidence of their war crimes.

Eliciting grief

American gender studies scholar Judith Butler argues Western media weaponise images to construct a hierarchy of grief that determines whose life is publicly mourned.

Publishing a war photograph is not just an act of documentation – it’s an act of interpretation. It shapes what others think is happening. In their book Picturing Atrocity (2012), Nancy Miller and colleagues ask us how we can witness suffering without turning it into spectacle.

The book raises important ethical questions. Who owns an image of someone suffering? What if the person photographed has died? What if the image perpetuates violence that hurts those closest to it?

A war photograph does not stop a missile. It does not feed a starving child. But it can interrupt denial and silence.

It can insist that something happened – and reinforce, as many of the placards on the Harbour Bridge said, “you cannot say you didn’t know”.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Sara Oscar, University of Technology Sydney and Cherine Fahd, University of Technology Sydney

Read more:

- Is Israel committing genocide in Gaza? International court will take years to decide, but states have a duty to act now

- Japan’s shifting memory of the second world war is raising fears of renewed militarism

- Bendigo Writers Festival has questions to answer over ‘untenable’ code of conduct for authors

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The Conversation

The Conversation

America News

America News Raw Story

Raw Story CNN

CNN Associated Press Top News

Associated Press Top News Reuters US Economy

Reuters US Economy Hello Magazine

Hello Magazine Deadline

Deadline