Ash is the new kid on the block. He’s in love with his best mate James, who he met some months prior on hookup app Grindr. Alas, James’ heart has been stolen by the mysterious Raf.

One evening, Ash spies Raf in a disturbing altercation nobody seems to want to discuss. This is followed shortly by an act of sudden brutality Raf is implicated in – one with the tendency to shut down conversations. Perhaps these incidents are products of Ash’s jealous imagination. Or perhaps Ash has an opportunity to expose his opponents’ wrongdoings and win over James.

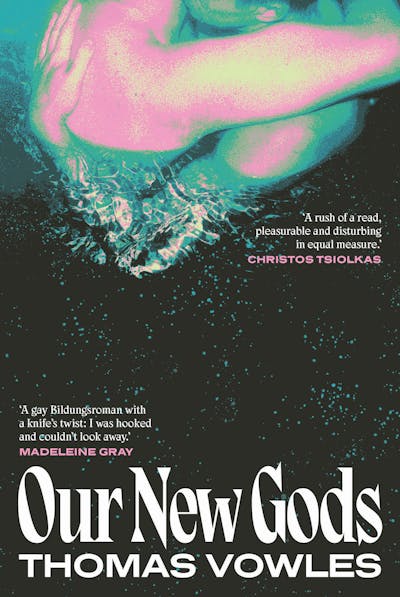

Review: Our New Gods – Thomas Vowles (University of Queensland Press)

Our New Gods, the debut novel from Melbourne writer Thomas Vowles, is among the latest in LGBTQI+ Australian fiction. The descriptions of sordidness and sex in inner-city Naarm are reminiscent of Loaded (1995), the debut novel of Christos Tsiolkas – who has praised Vowles’ book. I was reminded at different points of two queer classics from Alfred Hitchcock, Rope (1948) and Strangers on a Train (1951).

Our New Gods, a gay coming-of-age story, traverses more psychologically complex territory than some others in this field. When twentysomething Ash arrives in Melbourne seeking a “new version” of himself, he’s fleeing a country town and a joyless upbringing.

Suspense in the unsaid

Ash desires James, we realise, because he embodies the sexy, street-smart future our protagonist so desperately seeks. James is described in comically beatific terms, as being “on another level in terms of physical appearance and confidence […] he could have anyone.” Ash’s desire blinds him to the reality of the events playing out around him.

Indeed, as the desire grows, the line between reality and fantasy, dream and waking life become increasingly opaque. This provides a key source of narrative tension. The reader is positioned as detective, assigned not only to work out what Raf did (or didn’t) do, but how much of what we are reading exists only in Ash’s mind.

Not everyone or everything is as it seems. James acknowledges this in his typically understated way when he raises a toast to “secrets … To never truly knowing anyone.”

Tension and suspense are also generated through what remains unsaid. Why is Raf described as “not a good man” by someone who abruptly refuses to elaborate? Why is James so reluctant to engage in conversation about what Ash claims to have seen: even when this has implications for his own safety and wellbeing, not to mention the “new life” he craves?

Vowles gives no answers to these questions, creating the sense of an unspoken conspiracy – perhaps engineered by Raf, perhaps by some omnipotent forces – that constantly threatens Ash’s thirst for a new beginning. This sense of something unseen and malignant is suggested even before the first disturbing incident, when he describes the young people surrounding him as being “in on something I’d have to learn”.

These might initially sound like the musings of a stranger in a new, tragically hip environment. They take on a sinister hue in light of what follows.

Unsettlingly human

As he attempts to unravel the accumulating mystery, Ash becomes the kind of miscreant he abhors. During one sequence, in which he breaks into a house for ostensibly noble purposes, I genuinely did hold my breath. I found myself identifying with the young man, hoping he would avoid being caught – while knowing the wrongness of his actions and the fragility of his emotional state.

These events play out against the backdrop of a Melbourne evoked with cinematic vividness, reflecting Vowles’ background as a screenwriter. The novel opens at a house party populated by “cool” young things with “jagged haircuts and dexterous fingers as they rolled cigarettes without breaking conversation”. The reader is transported through trendy, crowded eateries and a quiet beach at night.

Vowles brilliantly evokes the world of inner-city, share-house living: the pleasantries exchanged between cohabiters and the fleeting, emotionless goodbyes when they go their separate ways. One house is described in terms of its

creaking pipes and the mice in the kitchen and the ever-growing pile of mail for the ghosts of housemates past […] sagging walls and the algaed shower and the small, dusty window in the bedroom.

There is the wind that blows menacingly down a chimney, like a ghost from the past intruding mercilessly on the present.

Houses also adopt unsettlingly human qualities: “I stepped into the mouth of the house and was engulfed by swimming heat.” Mouths can be fun and sexy; they can produce the right kind of (metaphorical) heat. Mouths can also destroy their contents.

Our New Gods could so easily have been just another trite, predictable gay coming-of-age story. Vowles must be credited for moving this material in a more fresh and exciting direction.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Jay Daniel Thompson, RMIT University

Read more:

- ‘Deeply personal, urgently communal’: Jewish Australian women reflect on life after October 7

- ‘A country to be heard and danced’: journeying into Australia’s menacing interior spaces

- How the neoliberalism of ‘Hayek’s Bastards’ changed the world – and fuelled the rise of the populist right

Jay Daniel Thompson receives funding from the Australian Research Council for a collaborative study entitled 'Addressing online hostility in Australian Digital Cultures' (DP230100870).

The Conversation

The Conversation

The Babylon Bee

The Babylon Bee FOX News Politics

FOX News Politics FOX News

FOX News Raw Story

Raw Story PupVine

PupVine Essentiallysports Motorsports

Essentiallysports Motorsports MENZMAG

MENZMAG