Personality tests have become increasingly popular in daily life. From hiring to dating, they promise to help us understand who we are and how we are similar, or different, to others.

But do these tests paint an accurate picture? And could it be harmful to take them too seriously?

What are personality tests?

A personality test is an instrument designed to elicit a response that may reveal someone’s “personality” – that is, their patterns of behaving and thinking across different situations.

These tests can take the form of self-reporting questionnaires, such as the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (first developed in the 1940s) and the Big Five Inventory (developed in the 1990s).

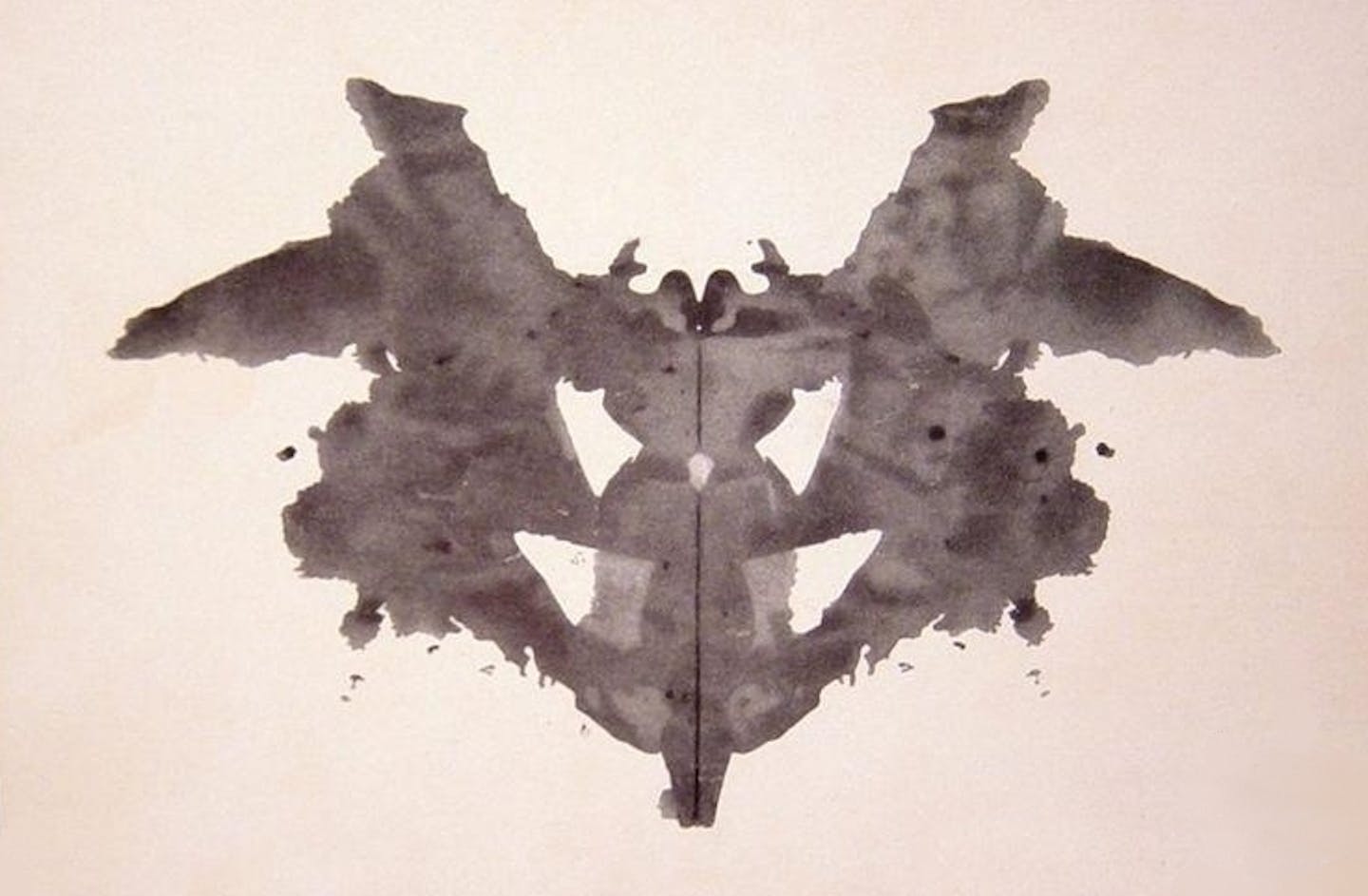

Or they may be “projective” tests, where the individual talks freely about their interpretation of ambiguous stimuli. One famous example of this is the Rorschach inkblot test, developed in the early 1920s by Swiss psychiatrist Hermann Rorschach.

Early beginnings

Personality testing isn’t new. Historical texts from across the globe suggest humans have been interested in understanding and categorising personality for thousands of years.

Around 400 BCE, Greek philosopher Hippocrates suggested an individual’s temperament was influenced by the balance of four bodily fluids, known as “humours”.

Even earlier, around 1115 BCE, government officials in ancient China examined the behaviour and character of individuals to determine their suitability for different jobs in the public system.

However, the systematic and scientific development of tools to understand and categorise personality only began in the 20th century.

One of the first was developed in 1917 by the United States army to predict how new recruits may react to war, and whether they were at risk of “shell shock” (now classified as post-traumatic stress disorder). The goal was to identify individuals who may be unsuitable for combat.

This assessment had 116 “yes” or “no” items, including questions about somatic symptoms, social adjustment, and medical and family history. Examples included “Have you ever fainted away?” and “Do you usually feel well and strong?”. Those who scored highly were referred to a psychologist for further assessment.

Since then, thousands of similar “personality” tests have been developed and used across clinical, occupational and educational settings. Many of these, such as the Myers-Briggs test, have gained mainstream appeal thanks to the internet and media.

Why are we drawn to these tests?

The answer to this lies not in the specific characteristics of the tests, but in the deep-seated psychological need they promise to satisfy.

The drive to understand oneself starts at an early age and continues throughout life. We ask ourselves questions such as “who am I?” and “how do I fit into the world?”

Personality tests are a simple way to get answers to these difficult questions. It can be quite comforting – even exhilarating – to see yourself reflected in the results.

According to American psychologist Abraham Maslow’s theory of human needs, people are driven towards self-improvement and “self-actualisation”, which broadly refers to the realisation of one’s potential.

So, people may be drawn to personality tests in the hope that knowing their personality “type” will help them make better choices for their personal growth, whether that’s in their career, relationships, or health.

Maslow also identified another human need: the need for belonging. Learning your personality type, and the types of those around you, is one way to find “your kind of people”. According to social identity theory, finding a group we feel we belong to feeds back into our sense of who we are.

The Barnum effect

It’s worth noting there is psychological research which questions the validity and reliability of the Myers-Briggs test.

One of the main critiques is that completing the test more than once within a short period of time can generate different results (what is called poor “test-retest reliability”). Since personality is generally stable in the short-term, you would ideally expect the same results.

Furthermore, Myers-Briggs and similar tests use broad, positive, and sufficiently vague language when describing personality types. In doing so, they effectively harness the “Barnum effect” or “Forer effect”: the tendency for people to accept general statements as unique descriptions of themselves.

Sound familiar? That’s because horoscopes do the same thing. The results of horoscopes and personality tests can “feel right” because they are designed to resonate with universal human experiences and aspirations.

That said, personality tests are still routinely used in research and clinical practice – although experts suggest using measures that are proven to be scientifically sound.

One common test used in clinical practice is the revised form of the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI-2-RF). This 338-item test measures problematic personality traits that may impact an individual’s mental health.

While it has its own set of problems, the MMPI-2-RF is useful in accurately assessing for symptoms of personality disorders, and predicting how different personality traits may impact treatment outcomes.

Taking tests too seriously

If you pigeonhole yourself into a rigid personality type, you run the danger of limiting yourself to the boundaries of this label. You may even use the label to excuse your own or others’ problematic behaviours as “just ESTP things”.

Moreover, by seeing the world purely through these simplified categories, we may ignore the fact that personality can evolve over long periods. By putting others, or ourselves, into a box, we fail to see people as individuals who are capable of change and growth.

While there’s nothing wrong with taking a personality test for fun, out of curiosity, or even to explore aspects of your identity, it’s important to not get too attached to the labels – lest they become all that you are.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Kelvin (Shiu Fung) Wong, Swinburne University of Technology and Wenting (Wendy) Chen, UNSW Sydney

Read more:

- Matcha latte for the likes: how ‘performative eating’ is changing our relationship with food

- Why do smart people get hooked on wellness trends? Personality traits may play a role

- Werewolf exes and billionaire CEOs: why cheesy short dramas are taking over our social media feeds

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The Conversation

The Conversation

Raw Story

Raw Story AlterNet

AlterNet FOX News Travel

FOX News Travel Deadline

Deadline America News

America News