New research conducted at Walufeni Cave, an important archaeological site in Papua New Guinea, reveals new evidence of long-distance interactions between Oceania’s Indigenous societies, as far back as 3,200 years ago.

Our new study, published in the journal Australian Archaeology, is the first archaeological research undertaken on the Great Papuan Plateau. The findings continue to undermine the historical Eurocentric idea that early Indigenous societies in this region were static and unchanging.

Instead, we find further evidence for what Monash Professor of Indigenous Archaeology Ian J. McNiven calls the Coral Sea Cultural Interaction Sphere: a dynamic interchange of trade, ideas and movement over a vast region encompassing New Guinea, the Torres Strait, and north-eastern Australia.

Tracking movement across Sahul

The goal of the Great Papuan Plateau project was to determine whether the plateau may have been an eastern pathway for the movement of early people into north-eastern Australia, at a time when New Guinea and Australia were joined in the continent of Sahul.

The two countries as we know them separated about 8,000 years ago due to sea levels rising after the last glacial period.

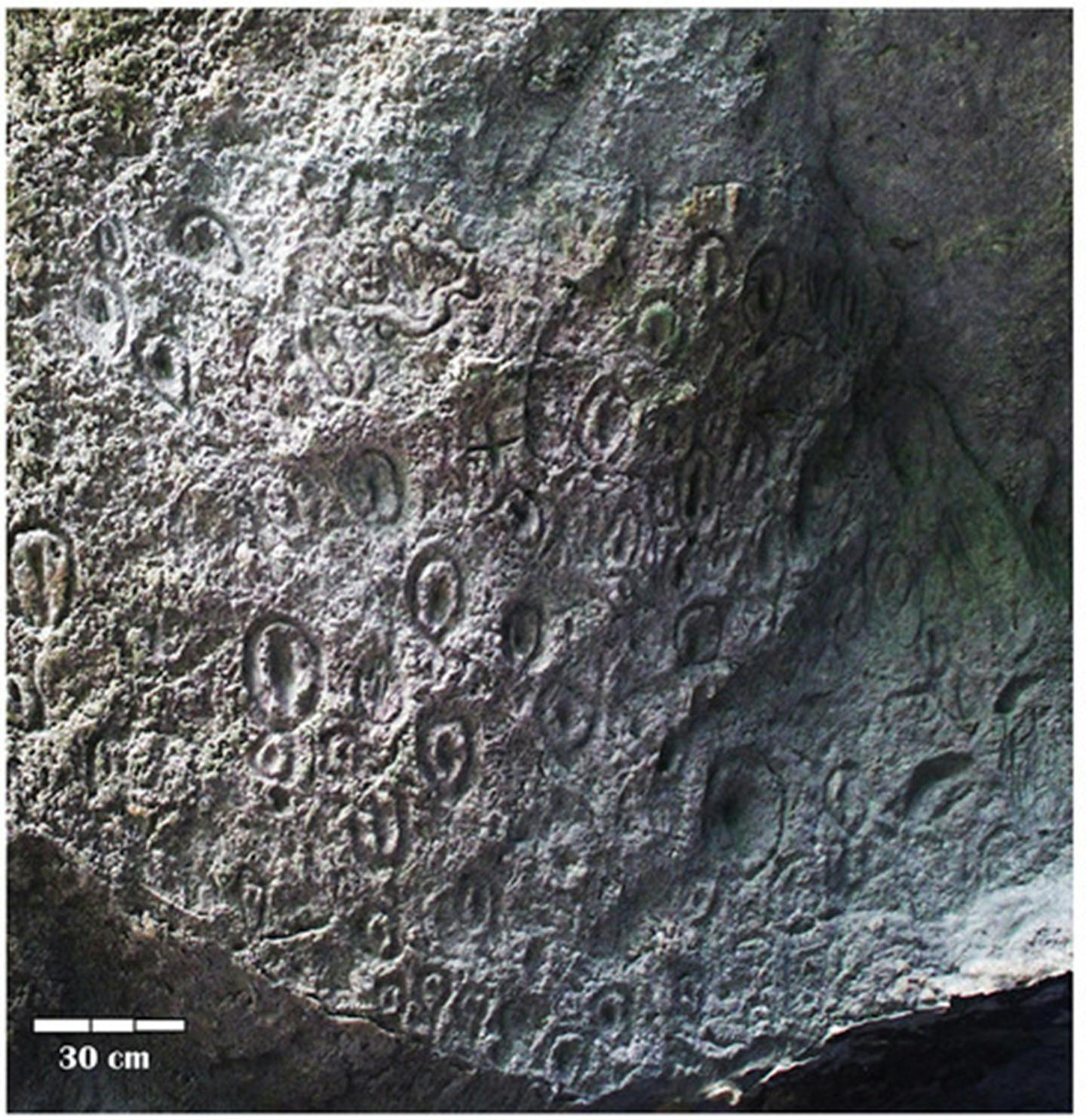

Our research in Walufeni Cave, located near Mount Bosavi in New Guinea’s southern highlands province, identified occupation dating back more than 10,000 years. We also found a unique and as yet undated petroglyph rock art style.

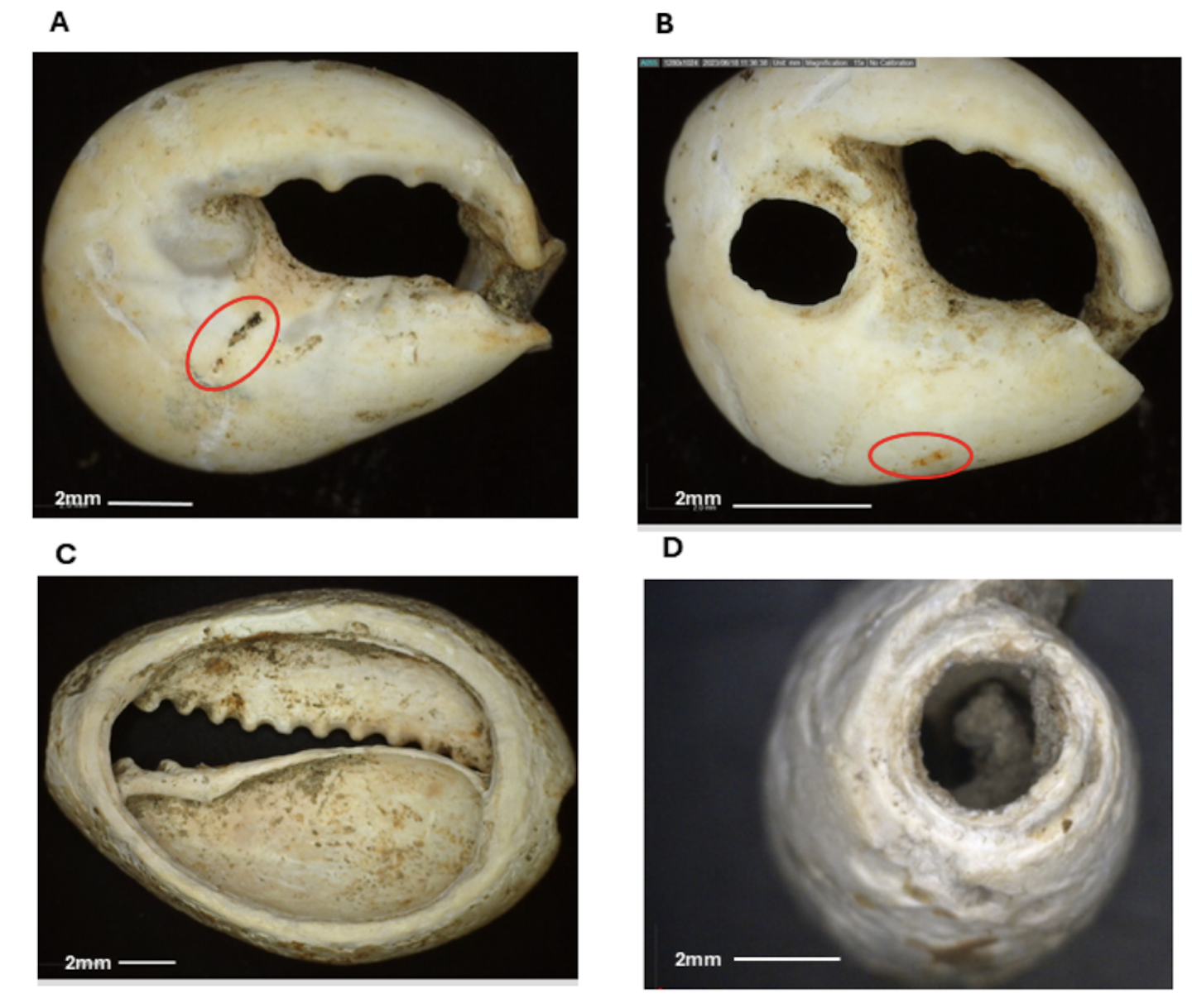

Our analyses of cave deposits reveals significant changes in how the site was used starting from just over 3,000 years ago. This includes changes to the frequency of occupation, to plant and animal use, as well as the sudden appearance of coastal marine shell.

Specifically, we found 3,200-year-old evidence for the transport of marine shell 200km inland, which has previously been recorded as coming from the southern coast of the Gulf of Papua, and from as far away as Torres Strait.

This suggests the long-distance maritime trade and interaction networks between the societies of coastal southern New Guinea, Torres Strait and northern Australia extended far inland – and much further than previously known.

The significance of marine shells

Archaeologists and ethnographers have widely documented the use of culturally modified marine shells as important items of trade and prestige in New Guinea.

These shells were used as markers of status and prestige, for ritual purposes, as currency and wealth, as tools, and to facilitate long-distance social ties between groups.

Despite the coastal availability of a large variety of shellfish, only a relatively small selection are recorded as being commonly used in New Guinea.

The most prominent of these are dog whelks (Nassaridae), cowrie shells (Cypraeidae), cone shells (Conidae), baler shell (Volutidae), and pearl/kina shell (Pteriidae). Many of these are significant for ritual and symbolic functions across the Indo-Pacific and indeed, globally.

Dog whelks were the predominant species we found in Walufeni Cave, along with olive shells and cowrie shells. These come from very small “sea snails”, or gastropods.

All of the shells we found had been culturally modified, such as to allow stitching onto garments, or threading onto strings.

Gastropod shells continue to be used by today’s plateau societies. They may be sewn onto elaborate ceremonial costumes, or offered in long strings as trade items, or as bridal dowry.

Pottery and oral tradition

Further evidence for long-distance voyaging between the southern coast of Papua New Guinea and the Torres Strait and Northern Australia comes in the form of pottery.

Researchers have found Lapita pottery at two archaeological sites on the south coast of New Guinea (Caution Bay and Hopo). These have been dated to 2,900 and 2,600 years ago, respectively.

Lapita pottery is a distinctive feature of Austronesian long-distance voyagers with origins in modern-day Taiwan and the Philippines. Lapita peoples bought the first pottery to New Guinea about 3,300 years ago, providing the template for later localised pottery production.

In a separate finding, Aboriginal pottery dating back to 2,950 years ago was reported from Jiigurru (Lizard Island), off the coast of the Cape York Peninsula. While this pottery isn’t stylistically Lapita, the technology used to make it is.

Similar pottery dating back 2,600 years ago has been reported on the eastern Murray Islands of Torres Strait, and in the Mask Cave on Pulu Island, western Torres Strait. Analysis of the Murray Island pottery indicates the clay was derived from southern Papua New Guinea.

These studies suggest the Lapita peoples’ knowledge of how to make pottery spread to Torres Strait and northern Australia via the interaction sphere.

Furthermore, the cultural hero Sido/Souw, who is present in oral tradition on the Great Papuan Plateau, is also present in oral tradition from the Torres Strait and southern New Guinea. This demonstrates sociocultural connections across a vast area.

Our research builds on the continuing reevaluation of the capabilities of Indigenous societies, which were often characterised by early anthropologists as static and unchanging.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Bryce Barker, University of Southern Queensland and Tiina Manne, The University of Queensland

Read more:

- Enslaved Africans, an uprising and an ancient farming system in Iraq: study sheds light on timelines

- Vikings were captivated by silver – our new analysis of their precious loot reveals how far they travelled to get it

- Ancient Incans of all classes used coded strings of hair for record keeping – new research

Bryce Barker receives funding from the Australian Research Council .

Tiina Manne receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

The Conversation

The Conversation

CBS News

CBS News The Federick News-Post

The Federick News-Post ESPN Football Headlines

ESPN Football Headlines Raw Story

Raw Story FOX News

FOX News New York Post

New York Post America News

America News