The introduction of television in Australia in 1956 coincided with mass post-war immigration, initially from Britain and Europe, and later from Asia, the Americas and Africa. Both played a significant role in forming modern society.

Our new book, Migrants, Television and Australian Stories, explores this intertwined history across seven decades, through dozens of interviews with screen creatives, technical staff and migrant viewers.

We provide fresh insight into the ways television introduced migrant audiences to the “Australian way of life”, as well as how the screen industry responded to a need for cultural diversity and inclusion.

Migrants were active audiences

Migrants arriving in Australia after the second world war were keen television viewers, despite the relatively high cost of owning a set.

Vietnamese refugee Cuc Lam told us she purchased a bulky secondhand television from a charity shop soon after arriving in Melbourne in 1978. She watched shows such as Play School (1966–) with her young children, picking up English phrases in the process.

The arrival of SBS television in 1980 (a service dedicated to migrant communities) is often heralded as a landmark initiative in Australian multiculturalism.

However, several earlier music and variety program aimed to showcase migrant groups and “exotic” international entertainers. Some examples included ABC’s Café Continental (1958–61) and Latin Holiday (1961).

One 1957 episode of the childrens’ show Romper Room (1953–94) featured insights into Chinese culture (pictured in the header image). This was unfamiliar viewing for most Australians at the time.

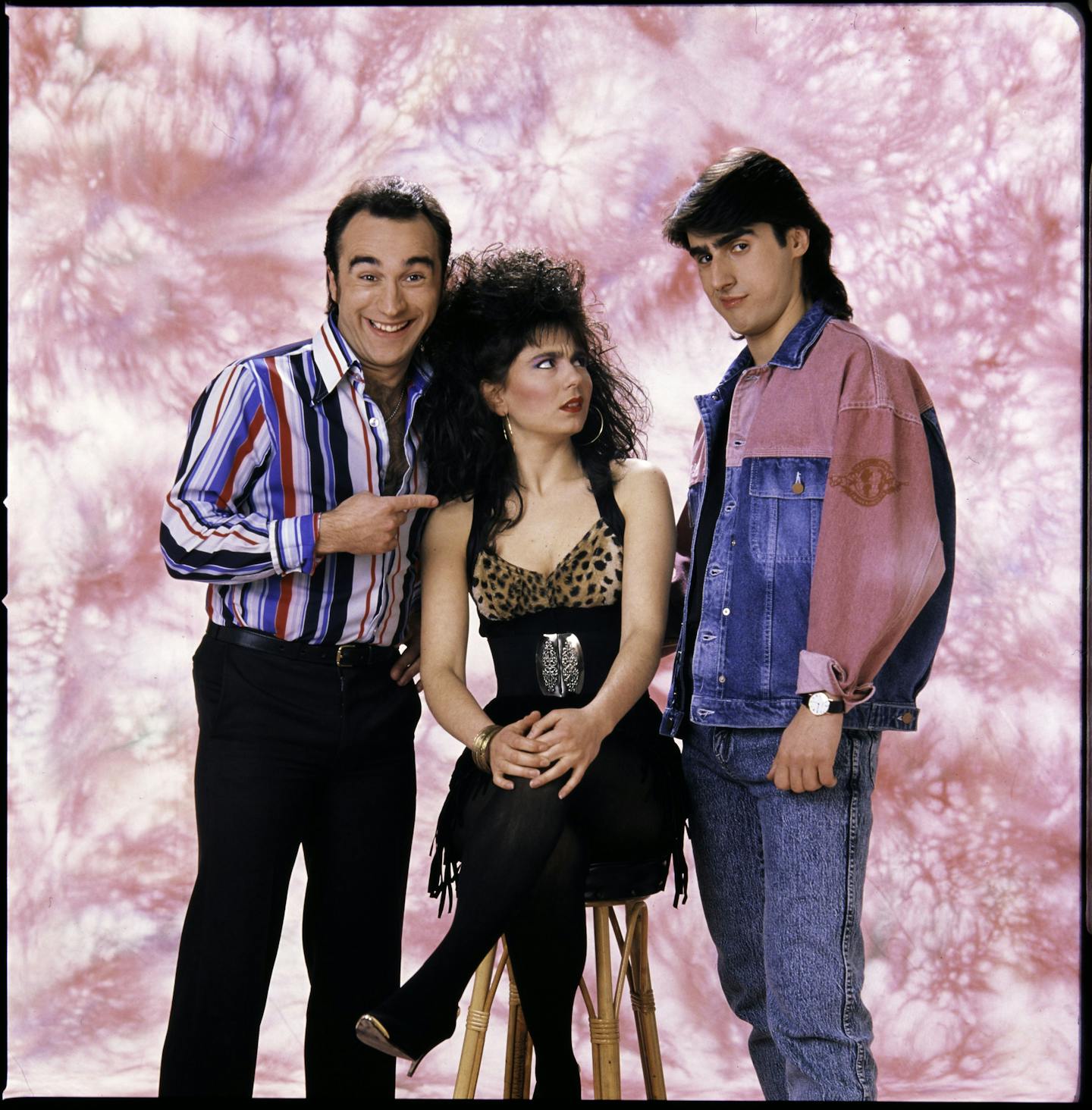

From the late 1960s, canny entrepreneurs with links to international diasporas produced shows such as the long-running Variety Italian Style (1972–87).

This commercial program featured music, cooking, travel, sport and documentary segments. It was sold to stations in North America and Europe, where it was broadcast to other Italian migrant populations.

Another such show was the Greek Variety Show (1977–84) produced by Greek Cypriot actor Harry Michaels, who also made the internationally successful Aerobics Oz Style (1982–2005). Michaels told us:

I was selling Greece to Australians, and then I ended up selling Australia to the world.

Representation on- and off-screen

Historically, many Australian-made dramas, comedies and other programs have reduced immigrants and other cultures to crude stereotypes.

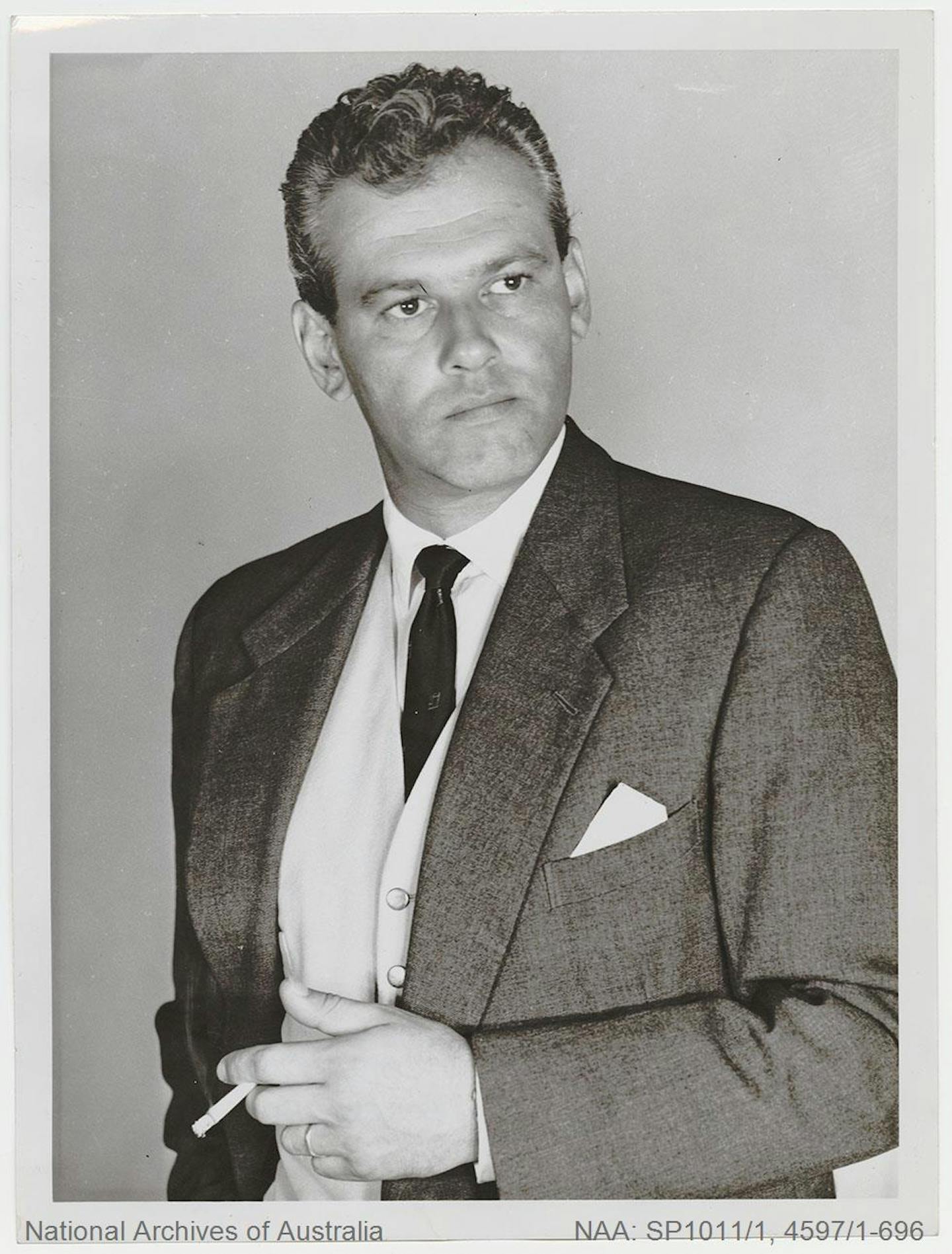

In the gritty crime dramas Homicide (1964–77) and Division 4 (1969–75), migrant characters were often portrayed as criminals or victims of crime.

This trend started to change in the 1980s and 1990s. Children of migrants began making their own successful shows that asserted their cultural identities. For example, Acropolis Now (1989–92) centred on the multicultural staff working at a Greek cafe in Melbourne.

Pauline Chan, a refugee of Vietnamese and Chinese backgrounds, worked on the landmark 1986 miniseries Vietnam, which explored the impact of the Vietnam War on a white Australian family.

Despite having worked in Hong Kong’s fast-paced film industry, she struggled to find work after arriving in Australia in 1982. Initially employed on Vietnam as a researcher, the production team quickly realised the value of Chan’s personal expertise. She ended up consulting, acting and working with Vietnamese extras. She said the project “was like going back into the past […] it was a very emotional experience for me”.

Viewing as a family ritual

Jasmina Pandevski, a Macedonian Australian from Wollongong, told us watching Hey Hey It’s Saturday (1971–99) in the early 1980s was a “bit of an event” for her family. Her father would make rice pudding as a special dessert to eat during the show.

World Championship Wrestling (1964–78) was also popular with viewers during its run on Channel 9. It routinely pitted overseas wrestlers against local stars.

Libnan Ayoub, the son of Lebanese migrant wrestler “Sheik” Wadi Ayoub, went as far as to describe it as Australia’s “first multicultural sport”.

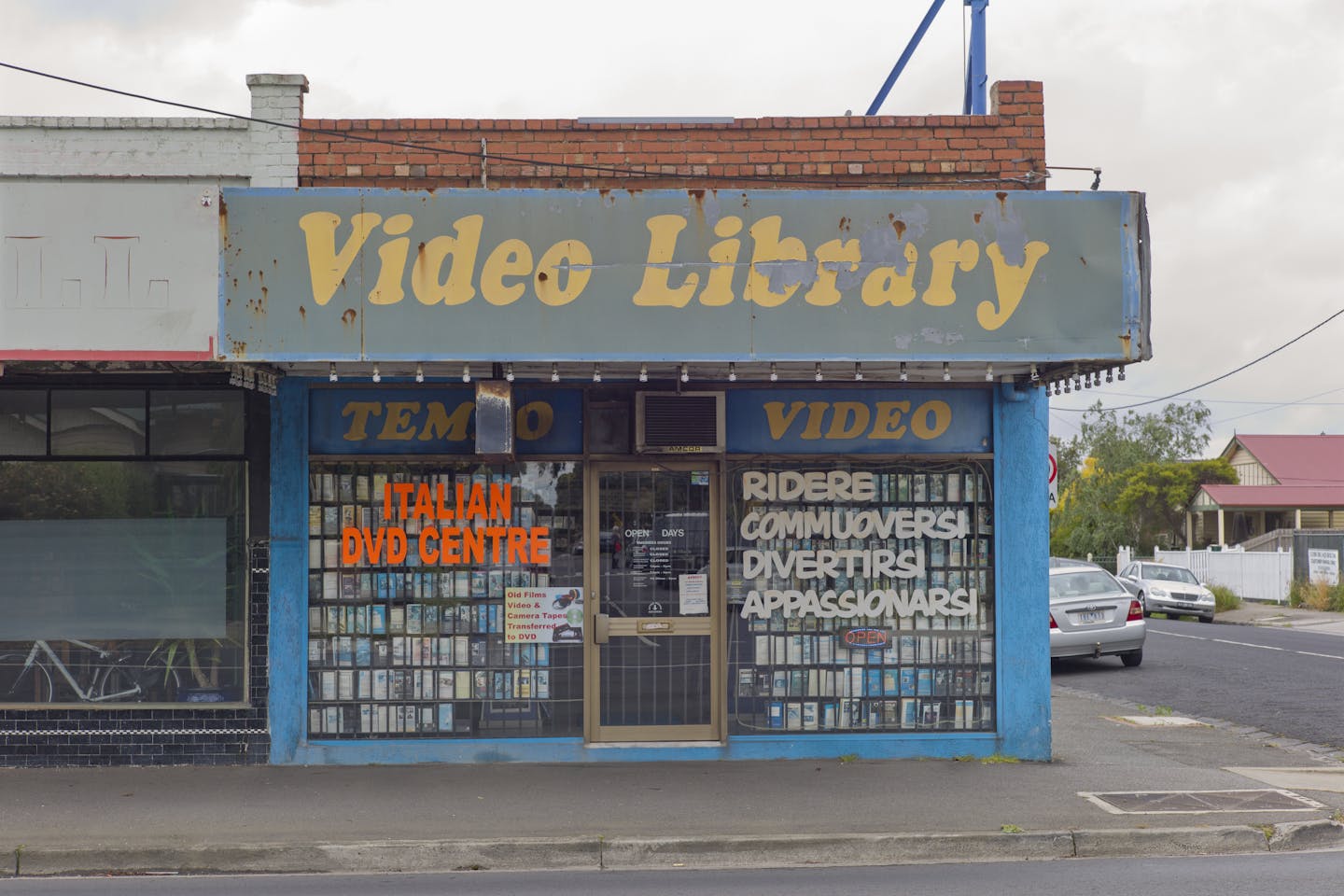

Family viewing changed with the arrival of the video recorder. Tala Jovanovski said her parents would source Macedonian videos of dance concerts and films from a neighbourhood shop. While they watched these videos in one room, she and her siblings were more likely watching Home and Away or Neighbours in another, eager to engage with Australian customs and teen culture.

Three siblings of Malaysian–Chinese background told us their conventional Australian children’s television diet was widened by their parents ownership of a video rental store in Brisbane. This meant they would also watch Jackie Chan’s kung-fu films. Now, they enjoy a new ritual of watching Eurovision with their own families.

We found today’s children and young adults of migrant backgrounds prefer the diversity of streaming platforms over commercial television. This corresponds with a wider trend of a preference for streaming.

Inclusion is an ongoing issue

Since the 1980s, a plethora of studies, surveys, forums and reports by media bodies, academics and advocates have suggested Australian broadcast media has been hesitant at best, and racist at worst, in representing cultural difference across scripted and unscripted television.

One 1990 report for the Office of Multicultural Affairs found “mainstream Australian media are neither competent in nor capable of accurately reflecting the diversity of Australian society”.

The situation has improved with gradual gains in access and opportunity for people from diverse backgrounds, along with significant policy changes – but only somewhat.

Actions to ensure diversity in Australian television remain ongoing. Some media creators use humour to critique the process of these well-meaning yet tokenistic efforts for inclusion.

Pearl Tan’s award-winning 2023 podcast Diversity Work, for instance, explores a fictional television writers’ room trying to tick off all its diversity “boxes”.

Tai Hara’s 2020 web series Colour Blind focuses on a hapless white casting agent navigating cultural sensitivities in the modern Australian screen industry.

Our research demonstrates migrants have always been important in producing and watching television. It also traces the continuing complexities of the question: what makes an Australian story?

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Kate Darian-Smith, The University of Melbourne; Kyle Harvey, Monash University; Sue Turnbull, University of Wollongong, and Sukhmani Khorana, UNSW Sydney

Read more:

- Politics with Michelle Grattan: Abul Rizvi on how silence and stalling stoke anti-migrant fears

- Underuse of migrants’ skills is costing us billions. Discrimination often starts at the job interview

- Albanese government sets unchanged 185,000 intake under permanent migration program

Kate Darian-Smith receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

Sue Turnbull receives funding from the Australian Research Council

Sukhmani Khorana receives funding from the Australia Research Council, and has previously undertaken commissioned research for Diversity Arts Australia.

Kyle Harvey does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The Conversation

The Conversation

Local News in Georgia

Local News in Georgia Local News in Florida

Local News in Florida KETV NewsWatch 7

KETV NewsWatch 7 Associated Press US and World News Video

Associated Press US and World News Video WKOW 27

WKOW 27 13 On Your Side

13 On Your Side Local News in Illinois

Local News in Illinois Raw Story

Raw Story Reuters US Top

Reuters US Top CBS News

CBS News