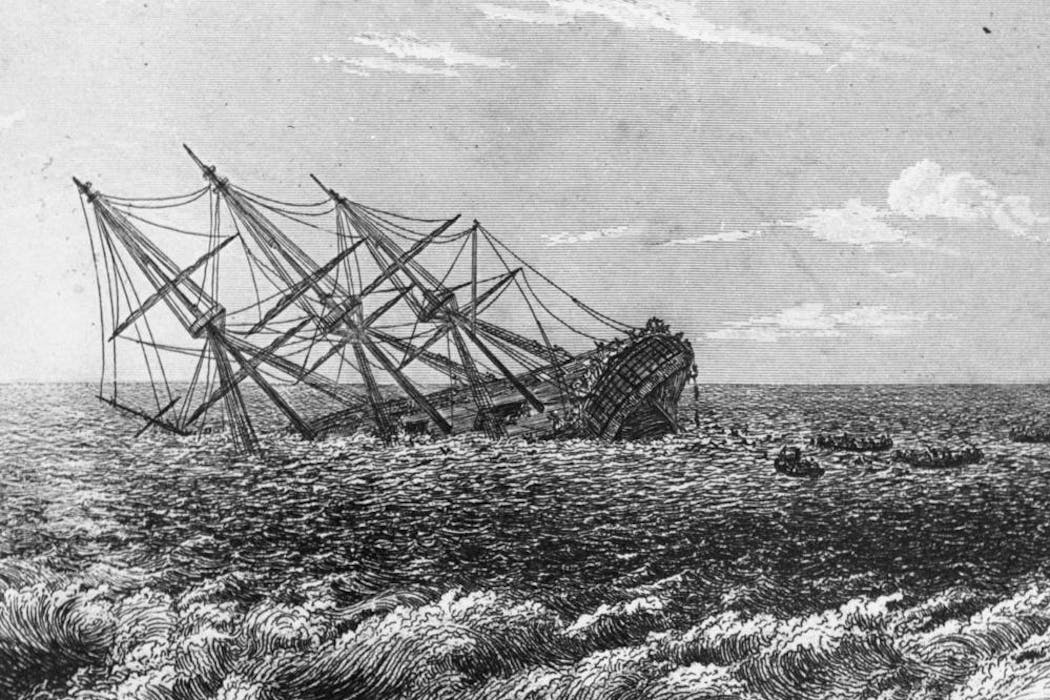

In 1791, the British naval vessel HMS Pandora sank on the Great Barrier Reef while pursuing the mutineers from the HMS Bounty. The mutineers, led by Christian Fletcher, staged an uprising against their captain Lieutenant William Bligh in 1789, forcing Bligh and his supporters out to sea in a launch.

This infamous act sent the fugitives fleeing across the Pacific, and set the stage for Pandora’s ill-fated pursuit.

When archaeologists first descended onto Pandora’s wreck in 1979, they weren’t just uncovering a ship. They were opening a time capsule of empire, exploration and human endurance. Thousands of artefacts were slowly excavated from the frigate over the next 20 years.

For decades, these recovered artefacts remained a sleeping archive of untapped scientific, cultural and environmental knowledge. But researchers are starting to study the collection again using fresh eyes and new tools.

The story of Pandora reveals a deeper truth about archaeology: discovery doesn’t end with the dive, it lingers in troves still sitting on museum shelves, waiting to be studied.

A moment sealed in time

The British Navy dispatched HMS Pandora in 1790 to hunt down the Bounty mutineers. A year later, the ship struck the Great Barrier Reef and sank, taking 35 men with it.

When the wreck was rediscovered in 1977, it became the focus of one of Australia’s most ambitious archaeological projects. Over nine field seasons between 1979 and 1999, Queensland Museum archaeologists recovered more than 6,500 artefacts.

These ranged from the ship’s copper fastenings and rigging blocks, to surgeon’s tools, creamware crockery, and Polynesian artefacts collected during encounters with Pacific Islander peoples.

Each object was meticulously recorded and conserved, creating one of the world’s most complete shipwreck assemblages from the 18th century. Despite its richness, however, much of the collection has never been studied in depth. And beyond the initial photographing and describing, researchers have yet to investigate the artefacts in depth.

The dormant years

Pandora was a triumph in the heyday of Australian maritime archaeology (the 1980-1990s). It put Queensland on the global map for shipwreck science, galvanised local communities, and even inspired the construction of a museum in Townsville – today known as the Queensland Museum Tropics – to house its finds.

By the time the final season on HMS Pandora wrapped up in 1999, the excitement that had fuelled two decades of fieldwork was fading. As funding dried up, attention turned towards consolidating the wealth of artefacts already recovered, and telling the ship’s story through the museum.

The museum currently displays 248 artefacts – about 4% of the total collection. By comparison, the British Museum estimates only about 1% of its eight million objects are exhibited at any one time.

Re-reading the past

Since the early 2000s, only a small fraction of the Pandora collection has been studied extensively. The thrill of excavation often outpaces the slower, less glamorous phase that follows: years of conservation, analysis, interpretation and publication.

Renewed research efforts are now reexamining the collection using up-to-date scientific and archaeological approaches.

One example is a 2023 study by myself and my colleague Alessandra Schultz, which involved carefully interpreting some of the smallest objects from the collection: the assemblage of intaglios and seals.

Intaglios are tiny engraved gems or glass pieces bearing motifs or classical images. They were once used as jewellery or personal seals, and served as sentimental keepsakes or tokens of moral protection. During long, dangerous naval voyages, they were carried for reassurance and good fortune.

Nine intaglios were recovered from Pandora. Many depict classical virtues, such as “hope” or “truth”. We studied them to better understand the mindset of Pandora’s crew as they set out to hunt down criminals.

The motifs themselves drew on the classical past: Atlas or Hercules symbolised endurance and burden; Hannibal evoked courage in adversity; Hope with an anchor embodied faith and safe return; Veritas stood for truth and integrity; and the figure of Hippocrates suggested wisdom and healing.

Collectively, they hint at how Pandora’s officers used classical imagery to express duty, morality and hope in times of uncertainty.

These personal European-made items were found alongside artefacts gathered from various encounters in the Pacific, suggesting the crew had a fascination with collecting “curiosities” (a popular pastime in 18th century Europe).

This overlap reveals a complicated picture of colonial exploration in which personal interests, cultural exchange and empire were deeply intertwined.

Scientific developments

We’ve made noticeable technological advances since the Pandora collection was first recovered. In particular, our ability to analyse the chemical composition of artefacts has vastly improved since the 1990s.

Using a technique called environmental scanning electron microscopy, we can take minute samples from shipwreck artefacts to understand exactly what they’re made of.

Applying this technique to seemingly boring artefacts, such as bolts and ceramic fragments, can give us valuable data to match to industrial advances throughout history, and allow us to trace these objects’ origins. We hope to apply this technology to the broader Pandora collection.

The Pandora collection carries deeply human stories. It is time we dived in once again to retrieve them.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Maddy McAllister, James Cook University

Read more:

- Friday essay: how ASIO spied on Australia’s Greek migrants during the Cold War

- Perfectly preserved rock art site reveals 1,700 years of Aboriginal string craft

- How Australia’s first outback mosque was built 600km north of Adelaide, 150 years ago

Maddy McAllister works for Queensland Museum as Senior Curator of Maritime Archaeology and is also a Senior Lecturer at James Cook University. She is affiliated with the Advisory Board for Underwater Archaeology and the Australasian Institute for Maritime Archaeology.

The Conversation

The Conversation

The Federick News-Post

The Federick News-Post Cover Media

Cover Media The Babylon Bee

The Babylon Bee Raw Story

Raw Story Fortune

Fortune US Magazine

US Magazine The Spectator

The Spectator Nola Entertainment

Nola Entertainment Newsweek Top

Newsweek Top AlterNet

AlterNet