When the rains end, creeks and rivers run full. Suddenly, deserts bloom with all the colours of the rainbow as new life emerges. As Tony Albert, artistic director of the Fifth National Indigenous Art Triennial, says, “After the rain there are always new beginnings.”

Albert’s creative practice has long been based on adapting and critiquing images made by others. It is easy to see this exhibition is a giant collage, where each work, or group of works, is an element of a larger whole, all working together in harmony.

Post the failed referendum, the participants are aware of what this time means for Australia’s Indigenous people. As Aretha Brown says in the catalogue:

It feels, after the referendum, as if everything has been burnt down, but now the seeds are going to come back stronger and greener.

The exhibition is introduced by Brown’s striking black and white mural, THE BIRTH OF A NATION: THE TRUE HISTORY OF AUSTRALIA, which shows her timeline of colonisation. Her **Kiss My Art Collective began as street art, reclaiming public space for Indigenous perspectives.

Shortly before the exhibition is due to close, Brown will paint over her mural, to demonstrate that the erasure of the past is very much a part of Indigenous Australia’s story.

Unlike previous exhibitions in this series, which were almost encyclopedic in scale, the space is confined to ten rooms, each with either a single artist or artists’ collective.

The mood of intimate collaboration is struck at the entrance where the artists are introduced – not by name but by images in the form of portraits painted by Vincent Namatjira. Their names are listed in small print to one side, but the images dominate.

The Namtajira legacy

Tony Albert has long been the master of collage, repurposing pieces of kitsch into critiques of the cultural blindness of white Australia.

It is no surprise that Albert has placed the art and legacy of Albert Namatjira as the very core of the exhibition.

Although his art was always popular with the general public, for much of the 20th century, those who saw themselves as arbiters of progressive taste regarded Albert Namatjira with open contempt.

In the 1960s, when a curator at the National Gallery of Victoria was ordered to exhibit one of Namatjira’s paintings, he hung it outside the ladies toilet, next to a bowl of gladioli. He thought he was being witty and his colleagues agreed with him.

Indigenous Australians always knew better. They understood he was a great interpreter, using a different visual language to paint Country in a style that white people could recognise. What artist and academic Brenda L. Croft calls “Albert’s Gift” was more than his art. His determination to be fully recognised by white Australia helped empower later generations of Indigenous people.

The room exhibiting art by the extended Namatjira family and the community of Ntaria/Hermannsburg is an explosion of paintings and ceramics. It is dominated by a stained glass interpretation of the house Albert Namatjira built at Lhara Pinta in 1944, where he lived for five years until cultural protocols meant the house had to be abandoned after the death of a child.

Lit from within, it shines like a jewel, throwing light on the many paintings and ceramics by Albert Namatjira, his children, grandchildren and other kin. His great-grandson Vincent Namatjira has painted Albert as a king, Royal Albert, the master of his land.

The South Australian artist Rex Battarbee became Albert Namatjira’s mentor. The installation includes Beth Mbitjana Inkamala’s exquisite ceramic facsimiles of letters written by Namatjira to Battarbee, exhibited alongside Rona Panangka Rubuntja’s recreation of Namatjira’s camera.

Many layers of beauty

Tony Albert appears to be guided as much by connections of friendship and kinship as by aesthetics or ideology. His long association with the Hermannsburg artists is well documented by the art they have made together.

But one of the most touching moments at the media opening was his introduction of the Aurukun artist Alair Pambegan, the creator of Kalben-aw Story Place of Wuku and Mukam the flying fox brothers, a reinterpretation of a Wik-Mungkan narrative from far north Queensland on the creation of the Milky Way.

People who live far away from city lights see the night sky in all its glory.

West of Aurukun, on the other side of the Gulf of Carpentaria, the Yolŋu artist Naminapu Maymuru-White, has painted Milŋiyawuy (Milky Way), where the stars of the Milky Way form rivers of pure light filled with different forms of life.

The installation extends to the ceiling, and visitors can lie on cushions and gaze at her version of the wonder of the night.

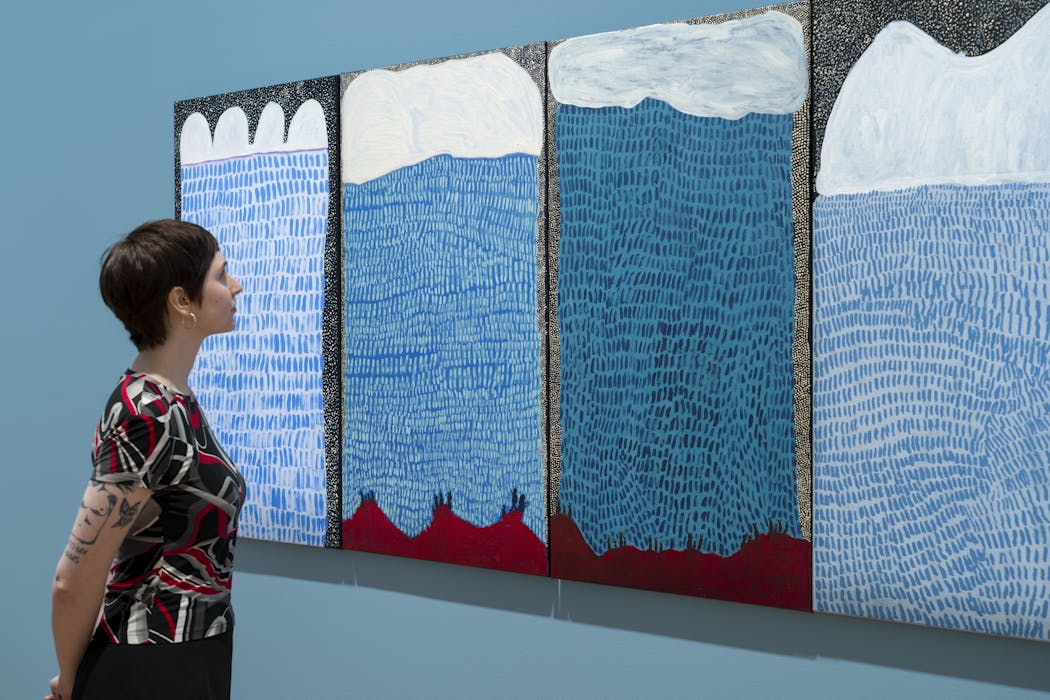

After the Rain is an exhibition of many layers of beauty, where the elegant design of Blaklash’s interior installations contrasts with Just Beneath the Surface, Jimmy John Thaiday’s beautiful, but unnerving video on the impact of climate change on the fragile ecology of the Torres Strait.

As Albert writes in the catalogue:

After the Rain does not seek to define, but to honour. It holds story, strength and sovereignty with care. It grows from Country. It speaks from artists. It moves with community.

The 5th National Indigenous Art Triennial: After the Rain is at the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, until April 26.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Joanna Mendelssohn, The University of Melbourne

Read more:

- An art historian looks at the origins of the Indigenous arts collection at the Vatican Museums

- A decade of Tarnanthi: how a festival of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art creates a new national art history

- William Barak’s missing art: Wurundjeri Elders lead the search to reclaim lost cultural treasures

Joanna Mendelssohn has in the past received funding from the Australian Research Council.

The Conversation

The Conversation

Esquire

Esquire NBC Chicago Sports

NBC Chicago Sports AlterNet

AlterNet The Shaw Local News Sports

The Shaw Local News Sports The Daily Beast

The Daily Beast Raw Story

Raw Story New York Post

New York Post America News

America News The Babylon Bee

The Babylon Bee