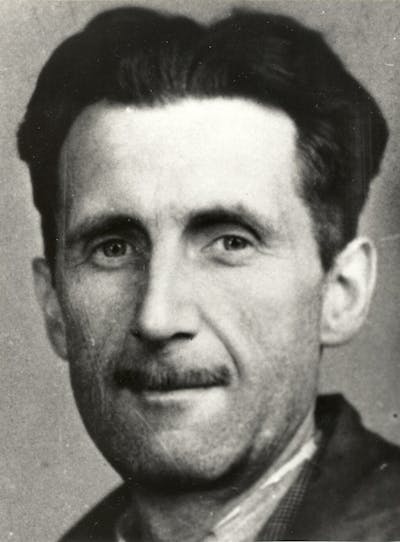

George Orwell’s Animal Farm (1945) turns 80 on August 17 2025. If there’s one thing every student of history or politics knows, it’s that the novella is not really about animals. Sure, the principal characters are pigs and horses. But really, so we are told, it is about the Soviet Union and what happened to the ideals of communism under the corrupt leadership of Joseph Stalin.

Orwell himself – part of a generation of plain-speaking British authors who had not yet heard Roland Barthes’s theory of the death of the author (the idea that words speak for themselves and the author’s intentions are irrelevant) – proclaimed that this was how the story should be read.

But what if we were to take the animals in this famous tale more seriously?

Orwell wrote this short, shocking novel at a time when it was considered scientifically inadmissible for animals to be granted thoughts or even feelings. Charles Darwin’s insight in 1859, that humans are related to all other animal species, was a lost opportunity to think about how qualities of the former might be present in the latter. Instead, animal psychologists in Orwell’s time insisted more strongly than ever on the existence of a cognitive hiatus between the human “us” and the beastly “them”.

This article is part of Rethinking the Classics. The stories in this series offer insightful new ways to think about and interpret classic books, films and artworks. This is the canon – with a twist.

His contemporary experts in the social sciences and humanities played along with this distinction. The French anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss wrote in 1962 that animals “are good to think with” – in other words, if we interrogate human beliefs about animals, we can reveal our own deep-seated values and social patterns.

By today’s standards, and in the context of the sixth mass extinction, this seems like a regrettable statement. Contemporary multispecies studies reject the notion that animals are nothing more than a resource for humans, even a philosophical one.

By contrast, many cultures and societies around the world have traditions of interacting with animals in a manner that recognises their personhood. People who live alongside and even hunt other species very often come to closely understand their behaviour and agency.

A major UK academic project is investigating how these relationships are reflected in animal fables. Titled Rethinking Fables in the Age of Environmental Crisis, it fosters collaboration between scholars, artists and writers in imagining the unique worlds of different species including horses, rats, crows and spiders, in their fast-changing and precarious environments.

Living in an era before the comprehensive introduction of massive-scale, chemically assisted agriculture, Orwell was not so far removed from pre-industrial farming and its intimate knowledge of animals. His 1936 essay about the shooting of an elephant in Burma is filled with anguish at the suffering of a real animal.

In Animal Farm too, the starting point is animal suffering – the cruelties of the human farmer are indisputable. As Old Major, a wise and elderly boar, warns the other animals: “You young porkers … every one of you will scream out your lives at the block within a year.”

The fable changes if we hold on to this reality throughout. It is reiterated by Orwell later on in the story, when the cruelties of Pinchfield Farm are reported to the animals. Human tyranny is the enemy of the animals, and despite the betrayal of their hopes under the leadership of the pig Napoleon, the justice of their cause is never undermined.

Animal dreams

Orwell’s animal revolution, the overthrow of the farmer, is inspired by a pig’s dream. Old Major gathers the other farm beasts to tell them of his vision of “the Earth as it will be when Man has vanished”, and human exploitation of animals is no more. It’s the kind of description that would have the 20th-century animal psychologists turning in their graves. Animals with an inner life? Ridiculous!

Any dog owner will tell you that their four-legged friend has dreams – yet for decades, we allowed scientists to tell us they did not. Dog dreams are woven into the description of forest life created by anthropologist Eduardo Kohn. In his book How Forests Think (2013), Kohn argues that all animals think and imagine their future. Their survival – that fundamental driver of the farmyard revolution – is based on the ability to do so.

In one memorable passage, Kohn describes how a monkey must interpret the sounds of the forest and use them to predict possible outcomes (innocent crash or predator?) in order to live. Kohn’s animals live in a world full of meaning. The human power to make meaning through abstract language is just one example of a universal feature of life.

Dreams recur throughout Animal Farm, but are eventually driven out by words. The animals’ commandments, written on the barn wall, are deviously amended one by one to vindicate the pigs’ corruption.

Once meaning is externalised and objectified in the written word, it is susceptible to manipulation. Words can be rewritten and with them, the past. The animals become uncertain of their pre-verbal memories. Dreams disappear from the narrative.

Research in science communication has argued that recent trends in popular natural history respond to the desire of readers to be knitted back into the meaning of the more-than-human world that Kohn and others describe. For such a reader, Animal Farm can explore animal agency – and the fallacy of human exceptionalism.

Beyond the canon

As part of the Rethinking the Classics series, we’re asking our experts to recommend a book or artwork that tackles similar themes to the canonical work in question, but isn’t (yet) considered a classic itself. Here is Charlotte Sleigh’s suggestion:

It’s surprisingly hard to find recent western works of animal-voiced fiction for adults – perhaps because of anxiety about sounding childish. By contrast, Indigenous literature around the world is rich in animal tales. Native American Animal Stories by Joseph Bruchac (1992) has a great selection.

Contemporary non-fiction is stronger in exploring animal-centred stories. Helen Macdonald’s memoir H is for Hawk (2014) is a modern classic. Poets have also engaged with animal voices, such as Susan Richardson in Words the Turtle Taught Me (2018). And in visual arts, Fiona MacDonald of the art and research project Feral Practice asks, among other animal-centred questions, what would happen if ants curated a gallery.

This article features references to books that have been included for editorial reasons, and may contain links to bookshop.org. If you click on one of the links and go on to buy something from bookshop.org The Conversation UK may earn a commission.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Charlotte Sleigh, UCL

Read more:

- Julia by Sandra Newman: a vibrant retelling of George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four

- George Orwell really did have a stint in jail as a drunk fish porter

- How George Orwell justified killing German civilians in the second world war

Charlotte Sleigh does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The Conversation

The Conversation

Associated Press Top News

Associated Press Top News First Alert 4 News

First Alert 4 News Massillon Independent

Massillon Independent New Jersey Herald

New Jersey Herald The Spectator

The Spectator Savannah Morning News

Savannah Morning News 11Alive Atlanta

11Alive Atlanta America News

America News The List

The List Washington Examiner

Washington Examiner