We are all familiar with cherubs – small, winged children that have a status in Western art history as angels.

But did you know this image you hold in your head of a cherub is completely unlike the cherubs of the biblical and medieval traditions?

Here’s what you should know about these mythical creatures.

Cherubs were originally fearsome

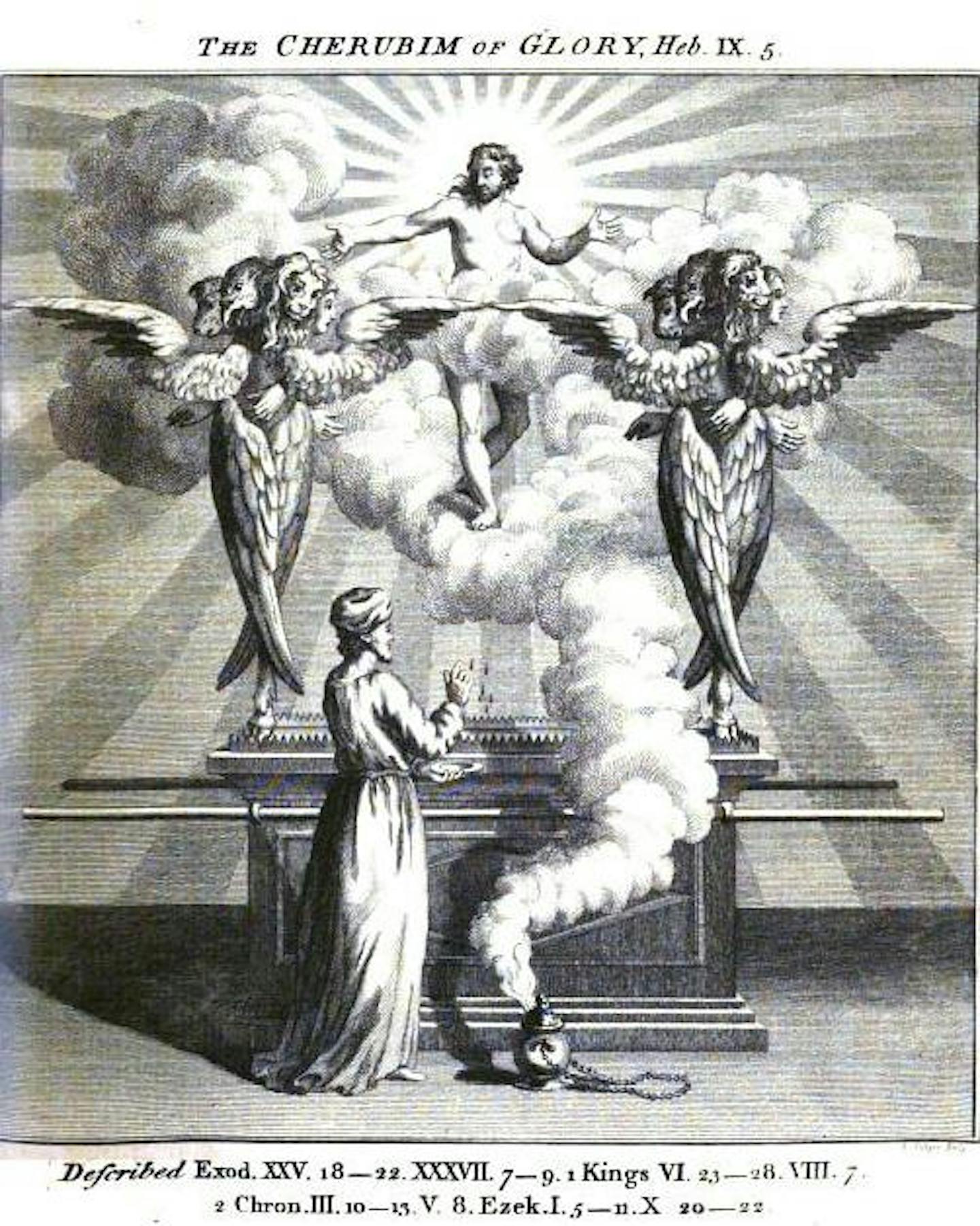

The Cherubs in the book of Ezekiel in the Old Testament were fearsome creatures.

Each had four faces – those of a human, a lion, an ox and an eagle – and four wings.

By the 4th century within Christianity, angels had become creatures with two wings, sufficient to enable them to travel from heaven, where they usually resided, to earth, generally to bring messages from God to us.

In the order of heavenly beings constructed by Pseudo-Dionysius in the late 5th century, Cherubs were second in importance to the Seraphs, followed by Thrones, Dominions, Virtues, Powers, Principalities, Archangels and Angels.

So, in the Dionysian order, Cherubs aren’t even angels, but are way above them, close to God. There, they supported the divine throne or the divine chariot by means of which God travelled around.

In a later tradition they, along with the archangel Gabriel, guarded the entrance to the Garden of Eden.

Cherubs as we know them come from Putti

What we now call Cherubs in Christian art were originally depictions of Putti – chubby, male children – from Ancient Greece and Rome. We are most familiar with a Putto as Eros, Amor or Cupid, usually naked, winged and with arrows used to incite love.

Putti were re-introduced into the West by the Italian sculptor Donatello in 1429 in sculpture.

In his art, the Putti were spiritelli – what we would call “sprites” or “elves”. They were little creatures – playful, lively and mischievous – often associated with love.

Suddenly, the Putti were everywhere. They especially adorned churches, playing with their Putti friends in childish glee, singing and dancing to the music of the lute or mandolin, climbing on fountains, pouring water through a vase or through the mouth of a fish.

The wings of the Putti suggested angelic status to Christian artists. And so, within the history of Christian art, these Putti have been and are still called “Cherubs”. But we do not know how they came to be known by this name.

The Putti became child-angels

In the 15th century, when the classical Putti were introduced into Christian art, they were looked upon as child-angels rather than as Putti. That is, they were Christianised.

We find child-angels with haloes and multi-coloured wings surrounding Mary and Jesus in Bernardino Fungai’s The Virgin and Child with Cherubim, painted around the end of the 15th century.

We know child-angels best of all as the two playful infantile figures of the Sistine Madonna (1514) with coloured wings, where Raphael has added them into the painting almost, it appears, just for the fun of it or as an afterthought.

Even Cherubs are not always Cherubs

Although we now might refer to all of these winged child-angels as Cherubs, the artists who painted them likely divided them into various celestial creatures, classified in some cases by the colour of the clothing they wore.

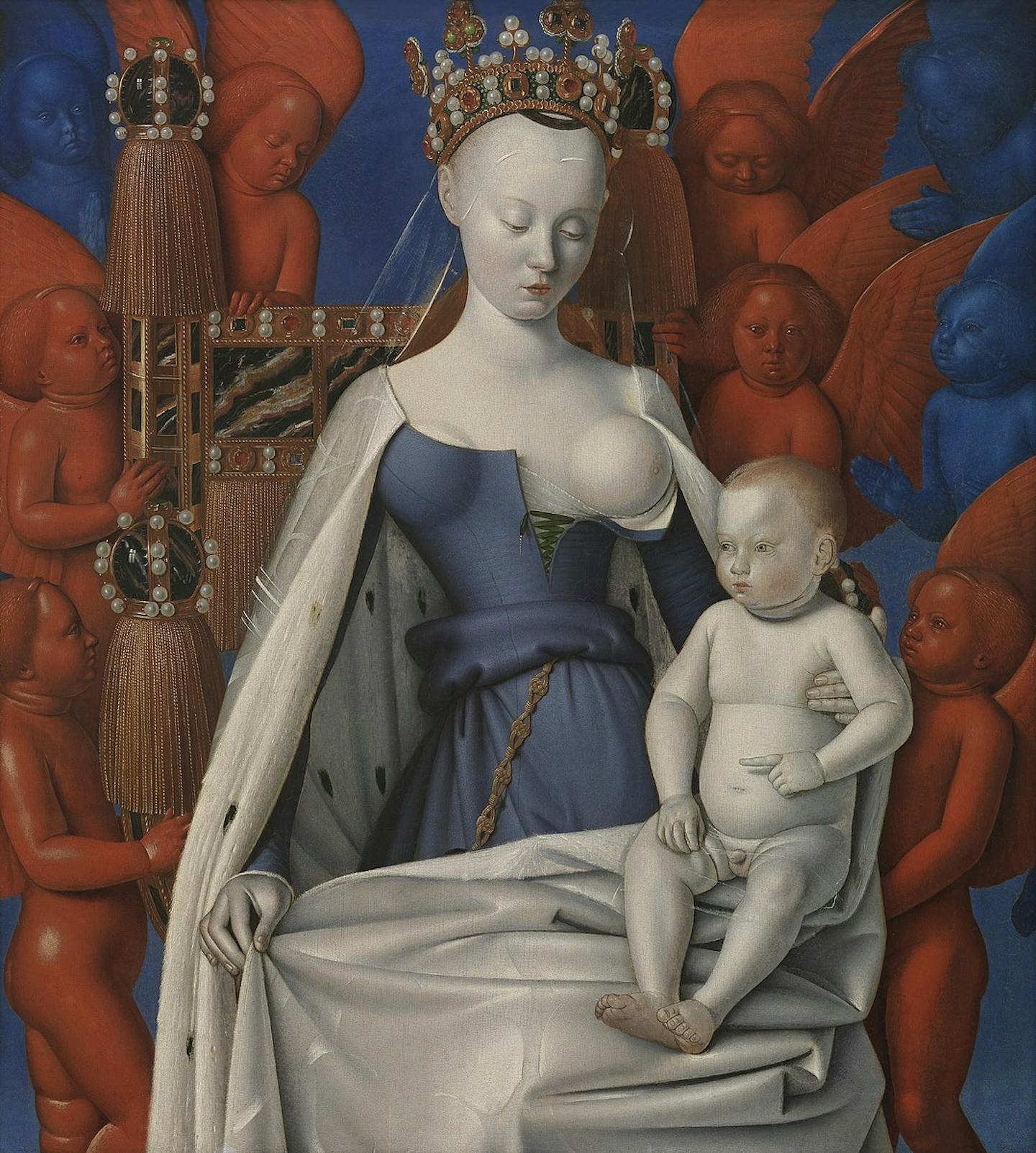

Cherubs often appear in blue clothing and with Mary, the mother of Jesus – their blue clothing perhaps reflecting her traditional blue clothes.

Child-angels dressed in blue are often paired with child-angels in red, the traditional colour of the Seraphs, those of a higher angelic order than the Cherubs.

In the French court painter Jean Fouquet’s Virgin and Child (1452), Mary the Queen of Heaven and Jesus are surrounded by naked red Seraphs and, behind them, naked blue Cherubs. So here we have the two highest orders of celestial creatures, surrounding Mary and Jesus.

On occasion, we find Seraphic infants only in attendance on Mary, now as winged heads, with no Cherubic children present at all.

Giovanni Bellini, in a 1485 painting known as Madonna of the Red Cherubim – but better titled “the Madonna of the red Seraphs” – has red winged, red-headed child-angels, their bodies in the clouds surrounding the head of Mary. It wasn’t until the 19th century that the name “Cherub” became common for all these baby angels.

But to call these child-angels all “Cherubs” is a misnomer, still perpetrated in Western art history.

Most artists just depicted child-angels or even infant-angels, with no connection to the biblical Cherub. That said, some, when dressed in blue, are probably intended as Cherubs; others, when dressed in red, are likely meant as Seraphs.

The history of the Western art of celestial creatures needs to be rewritten as a consequence.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Philip C. Almond, The University of Queensland

Read more:

- I entered an exhibition about North Terrace on North Terrace, and saw the precinct anew

- As a carer, I’ve spent hours in waiting rooms. My new artwork explores these liminal spaces

- Not First Nations, but want to wear First Nations fashion? Here’s what some community members think

Philip C. Almond does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

The Conversation

The Conversation

Sarasota Herald-Tribune Sports

Sarasota Herald-Tribune Sports Billboard

Billboard FOX News Videos

FOX News Videos Raw Story

Raw Story The Daily Record Weird News

The Daily Record Weird News AlterNet

AlterNet