The recent, sudden closure of Meanjin has brought renewed attention to Australian journals: those hardy perennials that support Australian literature year in and year out. While the sector has been suffering for some time, new entrants in Adelaide’s Splinter and First Nations journal Sovereign Texts – and a resurrected Southerly – reflect a surge of growth.

When Melbourne University Publishing issued a statement that Meanjin was being closed for “purely financial reasons”, the sector collectively baulked. A literary journal is not a profit-generating enterprise.

Breaking even is as much financial success as most of these publications aim for. The logic of capitalism is incompatible with journals. Like those other notoriously “loss leading” enterprises, tech start-ups, journals are about experimentation, training, play and provocation. Unlike tech-startups, journals are not made to sell once they start to turn a profit.

Instead, they feed their most valuable assets – writers and skilled-up editors – back into the literary system.

As Kent Macarter, from poetry journal Cordite, said in a recent Creative Australia report on the state of literary journals, they are “the breeding grounds and the petri dish of new talent”.

While these new journals, and existing quality journals such as Heat, Overland, Island and Griffith Review, are doing great work, the reality is that literary journals are under intense financial pressure. Current funding for journals, when provided by Creative Australia, is just enough for subsistence – not flourishing. The time for major government investment is now. If Australian arts were funded at a similar rate to our OECD peers, there would be plenty of funding to go around.

New journals on the block

Returning after a three-year hiatus is Southerly Journal. Begun in 1939, it held the mantle of the longest consistently running literary journal in Australia before it took a break in 2022.

Co-edited by Martu writer K.A. Ren Wyld and creative writer and academic Roanna Gonsalves, Southerly’s latest issue, First the future, features an impressive line-up of First Nations poets. They include Ali Cobby Eckermann, Kirli Saunders, Elfie Shiosaki, Jazz Money, Jeanine Leane and Natalie Harkin. It is dedicated to the memory of poet and visual artist Charmaine Papertalk Green, who died earlier this year.

Gonsalves described her vision for the new Southerly as “to continue to build on its glorious tradition”. That is, “to publish the finest Australian literature and scholarship, to be the home of the next generation of literary talent, to build a bridge between the academy and the secondary and tertiary sectors”.

Southerly is launching a new component to their work. Called “Barribugu” – “future” in Dharug language – this space on the Southerly website will be “a new home” for emerging writers in Australian high schools, where their work will sit alongside established Australian literary writers. “In this way we will mentor and champion the next generation of Australian writers, who have the literary talent but not the means to access circuits of publication and prestige,” Gonsalves told me.

The “hiatus” for Southerly shows just how perilous these enterprises can be – even in the case of the longest running publications that have enjoyed institutional support in the recent past. The University of Sydney used to be the journal’s home but now it is associated with the Literary Provocations Hub at the University of New South Wales.

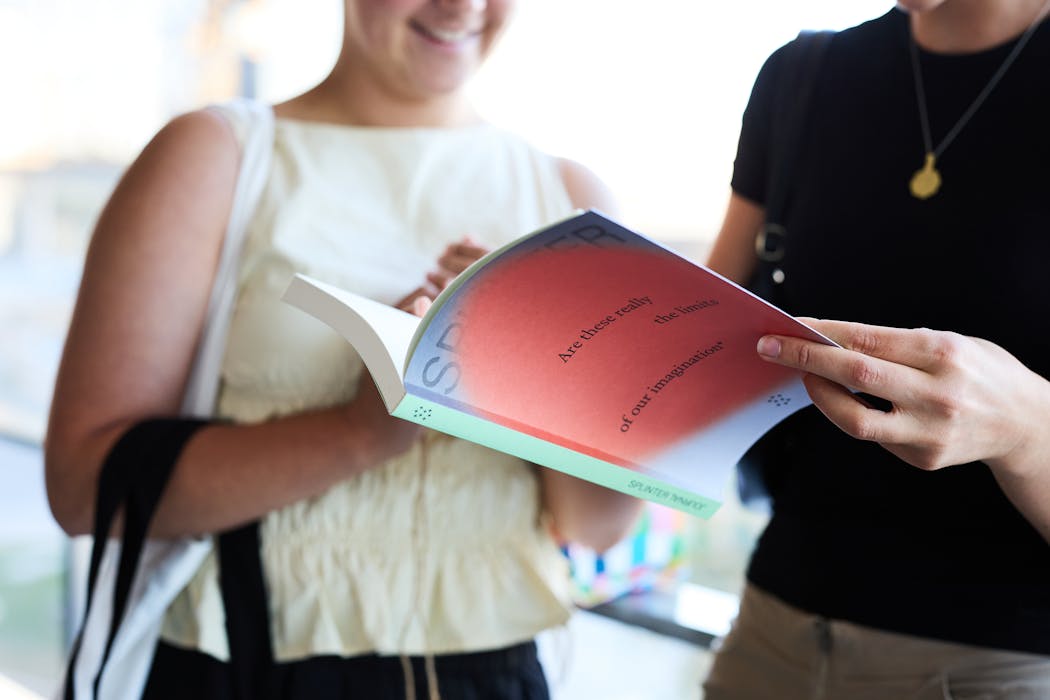

Last year, Splinter journal launched in South Australia. It is published biannually by Writers SA, with support from Flinders University, the University of South Australia and the University of Adelaide, along with Create SA. The merging of the latter two universities into the new Adelaide University (taking effect on January 1 next year) may well have repercussions for culture in the state. But the emergence of small publisher Pink Shorts Press and Splinter are promising developments.

Splinter’s third issue, published this November, is a dedicated First Nations one, edited by Gunai playwright and novelist Jannali Jones. It features authors familiar to Australian lit-watchers, such as Jeanine Leane, Nathan mudyi Sentance and Anne-Marie Te Whiu. But it also introduces some new voices.

I asked Splinter editor Farrin Foster what would help ensure the journal’s longevity. She replied: “long-term and secure funding”. She also noted that while Splinter does significant sales through their website, getting bookstore support is hard. “We often don’t have many marketing resources to support reps and booksellers in the way a book publisher might,” she said. “Everyone is doing their best, but I think this is eternally tricky for journals.”

In October 2025, another new journal was announced: Sovereign Texts, a self-described “journal for First Peoples literature, writing and storytelling”. Writer, researcher and community organiser Eugenia Flynn and Bridget Caldwell-Bright are editors and a prestigious board includes Graham Akhurst, Overland co-editor (and Stella Prize winning poet) Evelyn Araluen and associate professor in history, law and justice Crystal McKinnon.

The journal’s website proclaims a clear vision:

Our sovereignty as First Peoples is embedded throughout every element of this journal – our name, our cultural grounding, how and by whom we are governed, our editorial, editing and publishing processes, and most importantly who and what we publish.

The first issue is due to be published in June 2026.

‘A continual struggle to pay’

The Creative Australia report’s key findings focused on journals’ contributions and noted their precarity, with staff often forgoing payment for fear of drawing the ire of funding bodies. “It’s a continual struggle to pay all the people we want to pay and to be paid ourselves,” said Hollen Singleton of Going Down Swinging, which has published print and audio anthologies since 1979.

One way journals mitigate the risk of shrinking budgets or perilous funding arrangements is through partnerships with larger organisations – especially for their coverage of administrative support and editorial wages.

Established journals such as Overland (from 1954), Griffith Review (from 2003) and Sydney Review of Books (from 2013) all have affiliations with universities – Deakin, Griffith and Western Sydney University respectively. Another journal affiliated with Western Sydney is HEAT, published by Giramondo, which operated from 1996–2000, then 2001–11 – and was rebooted for a third series a few years ago, in 2022.

Tasmania-based Island, now edited by Jane Rawson, is one of the few journals that still prints in full colour. It has received funding from Creative Australia to produce an eight-page graphic narrative in each issue. It will also be running a four-day long readers and writers festival in Hobart next year.

Melbourne-based Kill Your Darlings started in print and is now online. It also produces book-form New Australian Fiction anthologies. It runs prizes and has a page on its website for “services”, including manuscript assessments, mentorships and writing programs.

University associations can provide stability for journals and support with administration or logistics. But the closure of Meanjin proved institutional affiliation is no guarantee.

Digital futures?

Two of these new journals combine print with an online presence, while Splinter is print only – demonstrating the resistance of literary journals to purely online incarnations. This may in part reflect that online is not a “cheap” alternative.

There remains a sticky misconception that online publishing does away with many of the costs of running a literary enterprise. While it’s true that printing and distribution are significant budget items, the bulk of the costs – including design, editorial and author fees – remain, whether the publication is online or not. And creating and maintaining a website is not free.

Liminal, which focuses on the Asian Australian experience, was founded in late 2016 and calls itself “an anti-racist literary platform”. Its stylish and readable website shows how attention to online design contributes to the reading experience. Liminal’s print anthologies of new writing further reflect a dedication to the aesthetics of the printed form.

Liminal, like Sydney Review of Books, or indeed The Conversation, makes work available for free on its websites. This means it’s far easier for content to spread.

In the same way a proliferation of streaming services splinters audiences, so too a range of journals with paywalls and subscription models means fewer readers, more silos.

Several Australian literary journals (including Overland, Griffith Review and Island) offer a bundle deal, where readers can get subscriptions to two journals at a discount. This is a good move. Other initiatives that could help attract wider readership include gift links, enabling subscribers to share a limited number of individual articles with a wider audience, or making content from past issues available for free.

Griffith Review, for example, offers some past content on their website and has a regular enews that features new and older writing, surfacing it for readers.

It’s time for serious government investment

Just as book publishers are facing rapidly increasing costs, so are literary journals.

As Catherine Noske of Westerly told former Sydney Review of Books editor Catriona Menzies-Pike and researcher Samuel Ryan, in their 2024 report on literary journals for Creative Australia, “the cycle of funding is exhausting”. That year-by-year thinking “makes it hard for journals to create any sort of long-term strategy”.

Australia is currently towards the bottom in terms of government spending on the arts compared with other OECD countries. To fund at the OECD average, of 0.5% of GDP, governments would need to increase arts funding by over A$5 billion per year.

I calculated the funds according to their current share by artform: literature received 3% of the total funding (at the federal level) in 2024–5. If the extra funds were distributed in a similar fashion to the Creative Australia share, it would equate to an extra $150 million dollars.

Just imagine what a literary journal could do with an additional million dollars a year. They might rent office space that could double as event space for launches. They might hire staff and pay them wages commensurate with their experience and talent – and not just the scraps left over after managing other parts of the budget. They might make their content freely available, helping increase readership.

This might sound outlandish – but if countries such as Canada, and Poland and Hungary choose to devote so much more of their money on the arts, why not Australia?

As the Menzies-Pike and Ryan report noted, right now literary journals rely heavily on low-paid or unpaid labour, perpetuating publishing’s class problem. By properly paying editors for their work, it’s possible to build a more diverse workforce, going beyond just people who can afford to volunteer their time.

The current funding guidelines from Creative Australia are better than when I edited a journal, Seizure, in 2010. Then, editorial was classed as “administrative work” and could not constitute more than 10% of the grant budget. But current funding for journals is just enough for subsistence, not flourishing.

There is a steady supply of authors and editors who feed into the publishing industry from journals. Seizure ran a successful novella project from 2012 to 2022; it was the one of the first places to publish some successful authors, including George Haddad and Mirandi Riwoe.

It gave the first taste of editorial work to people who are now publishers, editors and agents. (This happens with other journals too: for example, Brigid Mullane, now a publisher at Ultimo Press, was editor of Kill Your Darlings a decade ago.)

There is a massive cost to under-resourcing the journal sector: the editors and authors who don’t get the training and don’t go on to shape the future of the industry.

Literary journals are more important than squabbles about the size of the readership or concerns about financial returns: they are a fundamental part of Australian culture. The only way to guarantee long-term success is through major investment that will allow the journals to realise their ambition.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Alice Grundy, Australian National University

Read more:

- Want to make America healthy again? Stop fueling climate change

- Grim, funny and unremitting, Evelyn Araluen’s The Rot is a book attuned to dark times

- How extreme temperatures strain minds and bodies: a Karachi case study

Alice Grundy has received grants from the Australia Council for the Arts. She is Managing Editor at Australia Institute Press.

The Conversation

The Conversation

Fairbanks Daily News-Miner

Fairbanks Daily News-Miner Sweetwater Now

Sweetwater Now K2 Radio Local

K2 Radio Local People Human Interest

People Human Interest The Journal Gazette

The Journal Gazette Cleveland Jewish News

Cleveland Jewish News Newsday

Newsday CBS New York Business

CBS New York Business People Top Story

People Top Story